Arab Americans have a long history in Jacksonville tracing back to the 19th century. Between 1890 and 1920, hundreds of immigrants arrived and settled in Jacksonville from an area of the Middle East that is now home to the countries of Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine and other territories. Early settlers established themselves as grocers, peddlers and small-business operators, and dispersed throughout the city instead of forming ethnic enclaves. By immersing themselves in the dominant culture, they gained an unusual level of acceptance compared to other cities. At the same time, religious institutions and social clubs have helped generations maintain their culture locally. Today, the city now boasts the country’s fifth-largest Syrian population, and the 10th-largest overall Arab American community.

From business to politics to the food scene, Arab Americans have made waves in every aspect of life in Jacksonville for more than 130 years. Here’s a look at five sites with connections to Jacksonville’s illustrious Arab history.

1. David Brothers Building, 1730 North Main St.

As a teenager, Abdo David was employed as a clerk in a grocery store operated by his cousin Assad Sabbaq. By 1921, Abdo and younger brother Naif were business partners in Springfield. Their business, David Brothers wholesale dry goods, was located in this prominent building that anchors Historic Springfield’s 8th and Main district. The building was completed in 1910. Today, the Davis Brothers Building remains in use and is home to several retail shops.

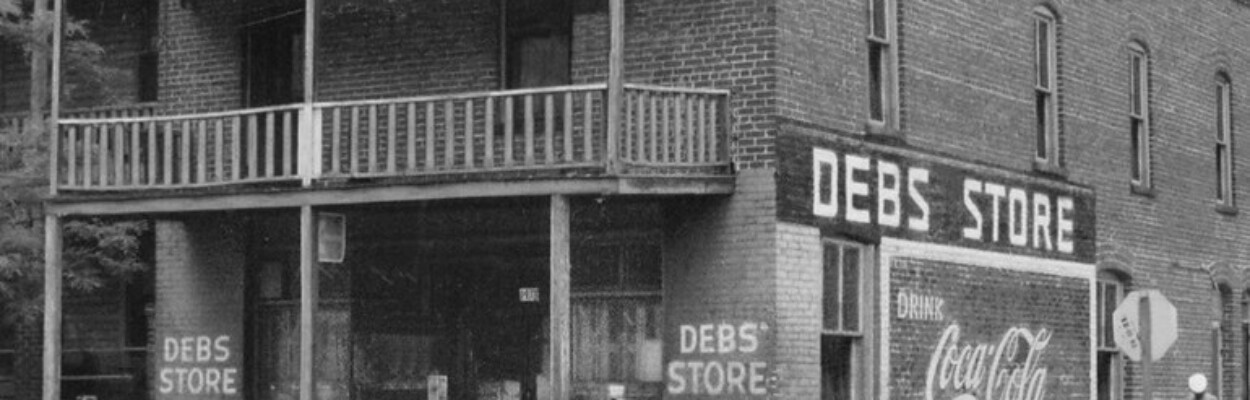

2. Debs Store, 1478 Florida Ave.

For nearly 100 years, the red brick building at the southwest corner of Florida Avenue and East 5th Street was an important symbol of vitality and life in the Eastside. Built in 1913 by African-American contractor Edward D. Mixson, the Debs Store operated as an old-fashioned neighborhood grocery market for the surrounding African-American community. Around 1928, the property was acquired by Nicholas and Rosa Debs. Prior to the purchase and moving their family into the second-floor apartment, the Debs had briefly operated their grocery business a few blocks east at 1738 Franklin St. after arriving in Jacksonville from Lebanon during the early 1920s.

Over the decades, the Debs Store grew into a neighborhood institution featuring fresh produce, meats, dairy and other products. Generations of neighborhood kids grew up knowing to “go to Debs” for their groceries, sundries, newspapers and any family necessity even if it meant putting the cost of the items “on the book” until such time as the family could pay. These same kids sent their kids and their kids’ kids to Debs daily to buy everything from fresh greens to handkerchiefs. It also became a place where neighborhood children were hired to stock shelves and make deliveries by bike. Following the end of World War II, sons Nick and Eugene Debs took over the Debs Store business. The Debs brothers continued to operate the Debs Store until they became too ill to maintain the business. When Eugene Debs passed in 2006, the family arranged for the funeral procession to travel along Florida Avenue and stop in front of the store, allowing a block of neighbors and friends lined on both sides of the street to greet Gene as he passed the store for the final time. Nicholas continued to run the business until falling ill shortly before his death in 2011.

An important and historically significant site to the Eastside community, plans are underway to restore the building into a grocery market and financial services hub designed to honor the past while also contributing to the economic stabilization of the surrounding community.

3. Syrian Presbyterian Church – Riverside, 702 Margaret St.

The Syrian Presbyterian Church was constituted in 1912 and incorporated in 1924. The congregation was established by Rev. A.E. Hazouri. Hazouri was from Sidon in the Ottoman province of Syria (now Lebanon), and resided at 601 1/2 Liberty St. in Springfield.

Most early Arab immigrants to Jacksonville were Catholic or Orthodox Christians, but a minority, including the Hazouri family, were Protestants. Hazouri formed the Syrian Presbyterian Church to serve the community, and preached in both English and Arabic.

In 1934, this red, rectangular, brick chapel with art glass windows was constructed for the church at 702 Margaret Street in Riverside. This 2,000-square-foot historic gothic structure is now the Five Points Chapel and Event Hall. The Hazouri family has remained influential in Jacksonville in a variety of fields. Members include Tommy Hazouri (1944–2021), who served as a state representative, mayor, Duval County school board member and Jacksonville City Council member; and Donna Deegan, a former newscaster, founder of a nonprofit for breast cancer survivors, and current candidate for Mayor of Jacksonville.

4. Azar & Company Wholesale Meats, 719 East Union St.

The original recipe for Azar Sausage was created by John Azar in 1954. Azar and his family had emigrated from Lebanon to the U.S. in the 1920s, eventually opening up a small grocery store on Florida Avenue in Jacksonville’s Eastside neighborhood. Sausage making became somewhat of a pastime for Azar, and before long, he was selling sausages out of the back of that grocery store. Word of Azar’s sausages spread and they gained popularity among locals very quickly. John eventually converted the family grocery store into a state-inspected sausage plant, and thus Azar Sausage Co. born. By 1960, Azar Sausage Co. had become a national brand when Azar’s son Raymond joined the company.

Today, Azar is still a family-operated company running on its third generation, using the same original family recipes. Azar products are locally available at Winn-Dixie, in some independent meat markets, served in several restaurants and Jacksonville Jumbo Shrimp baseball games. In addition, they sell in bulk at the East Union Street plant to anyone willing to pay them a visit.

5. Salaam Club, 8101 Beach Blvd.

Jacksonville’s early Arab immigrants quickly immersed themselves in the wider culture of the city, and in doing so found a wider degree of acceptance than in many other parts of the country. Nonetheless, generations of Arab Americans have worked to preserve their culture and traditions. Social organizations and churches have been instrumental in helping Arab Americans keep their culture alive in Jacksonville.

The oldest organization, the Salaam Club, was founded in 1912 as the Syrian American Club. It later merged with two other social clubs serving Syrian and Lebanese Americans: the Lebanon American Club and The Homs Brotherhood Club. Renamed the Salaam Club, its original building was located at the corner of 16th and Main Streets in Springfield. In 1959, the Salaam Club purchased its current 5-acre location on Beach Blvd. to accommodate further growth. The club continues to host regular events for members and its members have been active in all aspects of life in Jacksonville.

6. Ramallah American Club, 3130 Parental Home Rd.

In the 1920s, the collapse of the Ottoman Empire led to new wave of immigration from the Middle East to Jacksonville. Families in this wave were primarily Christians from Palestine, in particular the city of Ramallah. By the 1950s, Jacksonville was home to one of the largest populations of Ramallah descendents in the country.

In 1953, Palestinians in Jacksonville founded the Ramallah Club of Jacksonville, now the Ramallah American Club. The club building is located on Parental Home Rd. Like the Salaam Club, it hosts a variety of events and gatherings for its members, who have had a major impact on the city.

7. Farris & Company, 2116 West Beaver St.

Prior to World War II, the Rail Yard District was home to several meatpacking industry entities. In addition to stockyards, nearby meatpacking plants were operated by Jones Chambliss, Henry’s Hickory House, Armour & Company and Farris & Company. The story of Farris & Company began with Najeeb Easa Farris, a Syrian immigrant who was born on April 6, 1883. According to Immigrant Jacksonville: A Profile of Immigrant Groups in Jacksonville, 1890-1920, a UNF Digital Commons document. During the turn of the 20th century, Syrian immigrants in Jacksonville typically owned businesses selling produce, dry goods, and groceries. Adult members of the family worked with relatives until they could start their own establishments. In 1921, Farris constructed this four-story slaughterhouse after operating a LaVilla dry goods store since 1910.

The Farris slaughterhouse was estimated to cost $50,000 to construct. Architecturally, it was the opposite of the elegance found and cherished in the Prairie School style work of H.J. Klutho. According to the Meat and Livestock Commission’s Slaughterhouse Design Manual, the envelope of the buildings it describes should not be elaborate. Designed for the sole purpose to kill to produce saleable meat, slaughterhouses were a form of vernacular architecture. Recommended design characteristics included creating basic solid structures, free of exterior ornamentation and architectural embellishment to avoid high cost. C.L. Brooks’ design of the Farris & Company meatpacking plant was no exception to this rule.

Over the next four decades, products produced and sold by Farris & Company included neck bones, beef liver, pig tails, bologna, ribs, white bacon and Florida smoke bacon. Ultimately, the meatpacking plant’s demise came as a result of a 1960s fire that ruined its meat products, leaving it unable to fulfill contracts with Armour and Hormel. After its closure, the building was used as a cold storage warehouse for the N.G. Wade Investment Company.