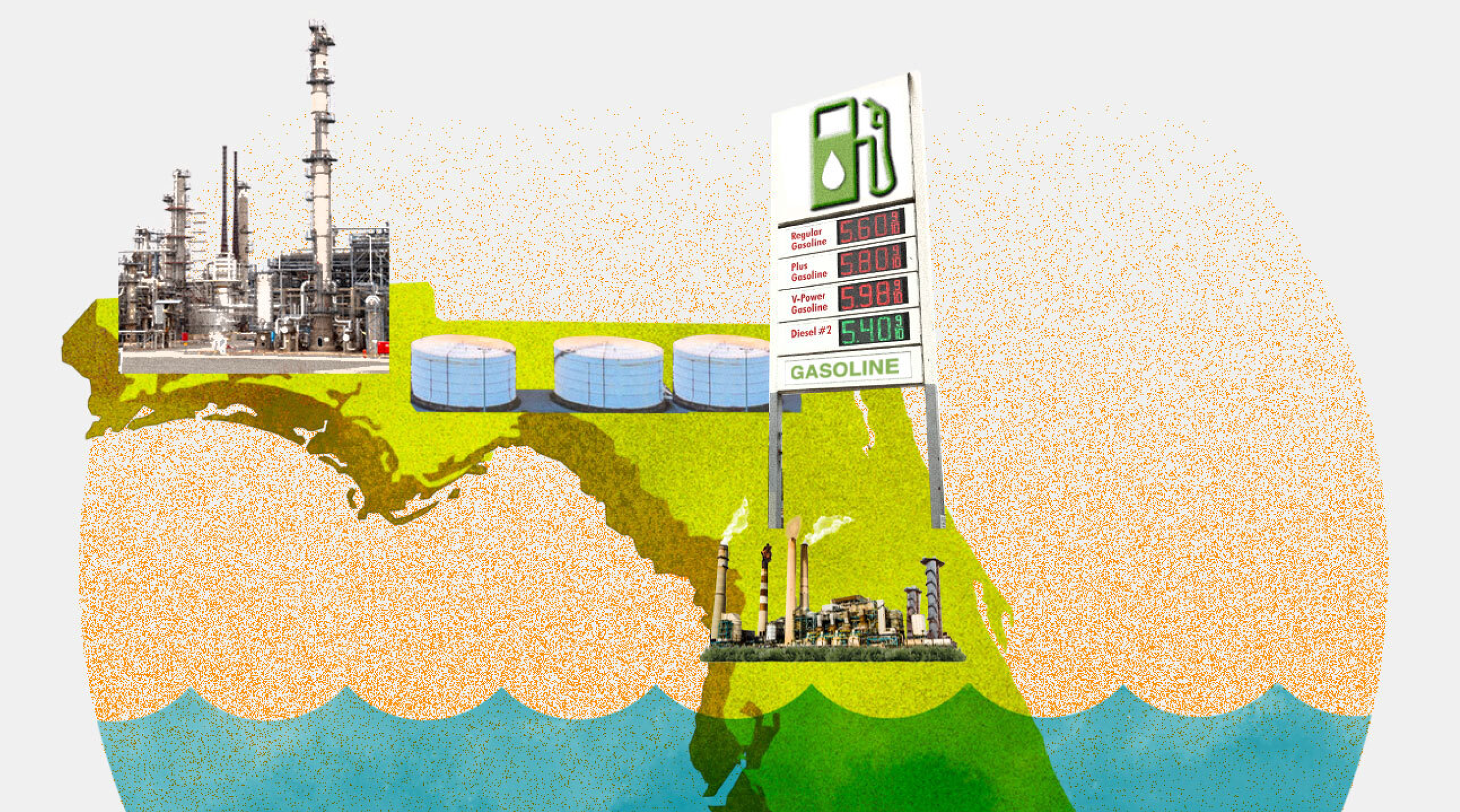

The story behind Florida’s new laws that strip cities of their ability to fight climate change.

This reporting by Grist and ADAPT is a collaboration in partnership with Floodlight.

In January, Tampa was set to become the 12th city in Florida to set a climate goal to transition to 100% clean energy. But that was before the natural gas industry and Republican state lawmakers got involved.

Tampa City Councilman Joseph Citro had worked for months with environmental groups and local businesses on a non-binding resolution — more of a North Star for the city than a mandatory policy. As part of its clean energy goal, the resolution supported a ban on new fossil fuel infrastructure including pipelines, compressor stations and power plants.

Credit: Chris O’Meara, AP Photo

No state-level policies in Florida require reducing planet-heating emissions, and some federal and state lawmakers deny the science of human-caused climate change. So it’s been up to cities and towns to do what they can, like buying electric schoolbuses and powering municipal buildings with renewable energy. Increasingly, local governments are ramping up their ambitions.

At the same time, the gas industry has aggressively lobbied against local climate policies while simultaneously trying to get state legislatures to strip cities of their ability to restrict fossil fuels.

That fight was about to come to Florida this year, just as Citro was finessing the final language on his city resolution. Republican state Sen. Travis Hutson of Palm Coast introduced bills that would make Citro’s Tampa proposal illegal. Hutson wanted to prohibit cities from passing any policies aimed at regulating energy infrastructure or fuel sources.

Credit: News Service of Florida

The effect in Tampa was immediate. Within two days, an aide to the Democratic mayor of Tampa texted Councilman Citro urging him to pull the resolution. “You don’t want your resolution to be the impetus to overturn decades of sustainability work in cities across the state, and currently Tampa is being blamed for it,” strategist Marley Wilkes wrote in a text message obtained in a public records request by the nonprofit watchdog Energy and Policy Institute and shared with Grist and ADAPT. Citro obliged, issuing a statement that he would pull his resolution and instead support a narrower plan from Mayor Jane Castor to power city-owned buildings with renewable energy by 2045. Representatives for the mayor and Citro both declined to comment for this story.

But withdrawing the resolution didn’t stop what was in motion at the statehouse.

Lawmakers approved Hutson’s bills, and Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis signed them in June. Florida law now prohibits local governments from taking “any action that restricts or prohibits” energy sources used by utilities. (It also voids any such existing local policies, except in cities that own their utilities, like Jacksonville, Orlando and Tallahassee.) And it prevents local officials from banning gas stations or requiring gas stations to install electric vehicle chargers.

Credit: Rick Bowmer, AP Photo

Environmental advocates in Florida fear that the new laws are so broad that it’s not clear what local governments will be able to do about their energy-related emissions. For example, are local incentives for solar development prohibited because they might restrict natural gas-generated electricity?

“This is probably all going to get litigated at extreme expense to local taxpayers,” said Jonathan Webber, deputy director of the environmental advocacy group Florida Conservation Voters.

The Florida bill sponsors said they were responding directly to Tampa’s proposed resolution. Polk County Rep. Josie Tomkow, a Republican co-sponsor in the Florida House of Representatives, argued during a committee hearing about one of the bills that “activists across the nation, even right here in Florida, are pursuing bans on natural gas as an energy source,” noting Tampa in particular.

“Tampa was used as a talking point for industry to justify ‘why now,’” said Brooke Errett, an organizer for Food and Water Watch.

Burning natural gas for heating and cooking in buildings contributes about 10 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, and transporting it from oil and gas fields to buildings also emits heat-trapping methane. Because of that, cities have started to pass laws banning new natural gas appliances or encouraging all-electric homes.

Credit: Thomas Kienzle, AP Photo

The gas industry sees such efforts as an existential threat. In addition to backing the state preemption efforts, it has waged a lobbying campaign to convince lawmakers that gas can be a part of a “clean energy” future. So far, 24 state legislatures have considered or passed laws that preempt local governments from restricting the use of natural gas in buildings.

Emails obtained by the Energy and Policy Institute and shared with Grist and ADAPT, as well as campaign contribution records, illustrate how Florida gas companies supported the bills preempting local climate action and the lawmakers who sponsored them.

In Florida, the Tampa gas and electric company TECO registered six lobbyists to advance the preemption bills. TECO did not respond to requests for comment.

TECO also appears to have contributed, at least indirectly, to Hutson’s campaign. In October 2020, TECO gave $30,000 to Voice of Florida Business, a political action committee (PAC) that has pooled millions of dollars from the utilities industry in the last decade. That same day, Voice of Florida Business then sent $5,000 to a PAC associated with Hutson. It sent another $5,000 in March. In January, TECO also contributed $88,000 to a PAC called Associated Industries of Florida, which sent $5,000 to a second Hutson PAC in February.

Tomkow, a co-sponsor of the legislation, also received two $1,000 campaign donations, from TECO and another utility, Florida Public Utilities, in October. Neither lawmaker responded to requests for comment.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Additional records obtained by the Energy and Policy Institute demonstrate the industry’s lobbying efforts at both the local and state level. For example:

- TECO scheduled a January meeting with the mayor’s office to discuss the Tampa resolution

- Lobbyists from the oil and gas trade group the American Petroleum Institute who backed the state preemption bills were scheduled to meet with Citro five days before he pulled the city resolution

- A letter from the president of the Port of Tampa Bay, A. Paul Anderson, to the port’s board of commissioners outlined efforts by the Port of Tampa Bay — a major gateway for fuel imports — to weaken the resolution. “We have remained in constant communication with the councilman and his colleagues on the council in an effort to educate them of the negative effects this resolution will have on our tenants, our business, and our community’s economy,” the letter said, noting that port staff were participating in “weekly strategy calls to coordinate our with state partners.” A Republican lawmaker who co-sponsored one of the House bills, Tom Fabricio of Miramar, said the port was one reason he backed the legislation, calling it a “major hub through which the entirety of central Florida is supplied with [gasoline].”

- Investor-owned utilities are not the only ones who support local preemption. At least one city-owned utility was pushing for the legislation as well. In January, the public affairs manager for Clearwater Gas, a municipally owned gas utility in Clearwater, emailed the utility’s executive director, Chuck Warrington, saying that they should talk to their state senator about Hutson’s preemption bill. “If this guy gets it through I will send him money for his reelection campaign,” Kristi Cheatham Pettit told Warrington. Warrington in another email noted that the Florida Natural Gas Association, a trade group, was “championing” the legislation. Neither Clearwater nor the association responded to requests for comment.

- As far back as May 2019, the city of Clearwater was strategizing against efforts to limit gas use, including trying to hold meetings with cities and counties that were pursuing resolutions similar to Tampa’s. Warrington expressed concerns about climate efforts by the U.S. Conference of Mayors and argued for utilities to “aggressively” present their stance “with the same vigor as the extreme environmentalists.”

During hearings about the bills, Hutson, who lives in St. Augustine, denied that they would prevent cities from pursuing renewable energy and said they were instead meant to give state officials a say in Florida’s clean energy agenda. Yet renewable energy proposals have met stiff resistance in the Legislature.

Democratic Sen. Lori Berman of Boynton Beach said several bills she’s worked on to increase solar energy have either not gotten a hearing or failed to win enough support to pass.

“I think these [preemption] bills are part of a continuing effort on the Florida Legislature to thwart individuals from having their own solar energy and to protect the electric utilities, often at the expense of renewable energy sources,” Berman said.

Reaction from cities

Florida cities that are trying to cut their emissions differ in their interpretations of how the preemption bills will affect them.

Richard Kriseman, the Democratic mayor of St. Petersburg — the first city in Florida to set a goal of 100 percent renewable energy — said his city will be hamstrung. St. Petersburg had begun to develop new city codes to make buildings ready for solar power and electric vehicle charging.

“At this point there’s no point in us moving forward with putting those in place,” Kriseman said.

But John Regan, the city manager of St. Augustine, which is in Hutson’s district, said the bills would not have an impact on the city’s current climate plans. Regan said the city never had the authority to tell the electric utility, Florida Power & Light, how to generate electricity.

“The market and federal law will dictate those issues,” he said.

St. Augustine spends $5 million to $10 million every year on projects to address flooding and reduce emissions by reducing its energy consumption. Thus far it has mainly focused on installing motion-sensing lights and solar-powered parking kiosks, and making city-owned buildings more energy efficient, rather than mandating changes through its building codes.

In Tampa, Citro plans to re-introduce his resolution in early August after giving it a major facelift.

“They do want to still have a bold vision put forth through the resolution, but without triggering anything that may cause the utilities to sue,” said Errett, of Food and Water Watch.

“It’s going to be, most likely, a lot more of an aspirational call to action,” she said.