The Duval County public school district is asking retired school librarians to come back part-time, as it scrambles to comply with new Florida book laws that make the position vital to keeping books in kids’ hands.

“Only certified media specialists can review and approve books,” the district’s February letter to retired staffers reads. “We would greatly appreciate your expertise!”

The request comes as the district also grapples with a 20% vacancy rate in media specialist positions. Media specialist is the state’s title for what is historically known as a school librarian, and they’re a rarity in Duval Schools.

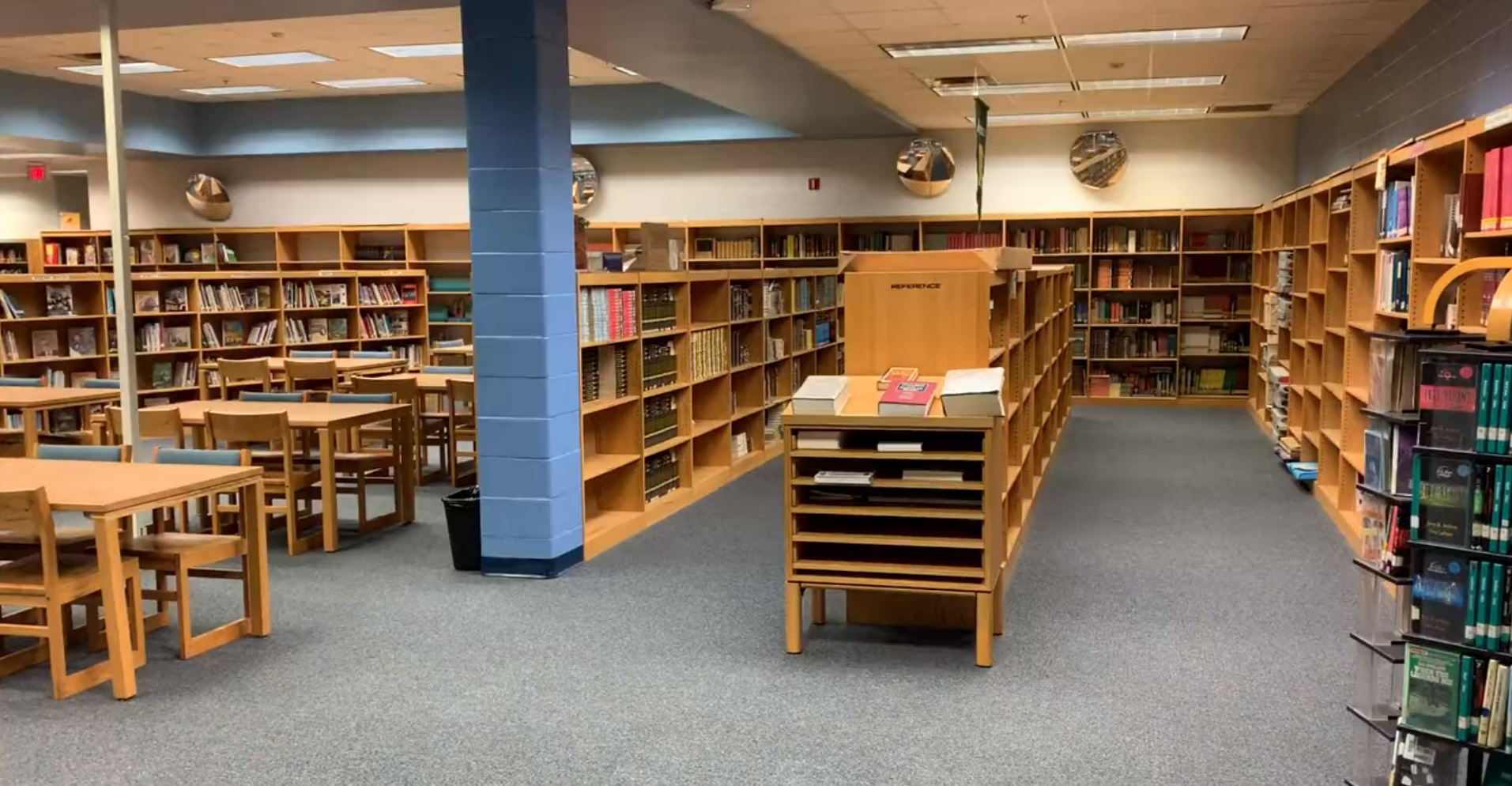

Duval used to have media specialists in most of its schools, but that changed in 2013 with budget cuts. Now, due to the cutbacks and current vacancy rate, just 33 elementary and K-8 schools have a full-time media specialist and 45 split their librarian with other schools. There are no media specialists in the district’s middle or high schools, according to district data.

Of the district’s 70 funded media specialist positions, 1-in-5 are vacant.

The district has steadily cut its media services budget, from about $12 million in 2013 to just about $5.5 million this year, budget records show. When Jacksonville Today asked about the cuts, a Duval Schools spokesperson wrote, “The district must make choices about how to invest resources to improve student and school outcomes. Over the years, we have invested in other strategies and it has paid off with school success.”

In surrounding counties, Clay Schools has full-time media specialists in every school in the district, Nassau has 15 media specialists for its 20 schools and St. Johns has 41 media specialists, the same number as it has traditional public schools. Duval County had among the fewest librarians per student in the state last school year, according to U.S. Department of Education data.

One current Duval media specialist, who spoke with Jacksonville Today on the condition of anonymity, said some colleagues are looking for other jobs and considering retiring early. “There’s a lot of librarians biding their time right now,” says the librarian, who didn’t want to be named for fear of retaliation, saying the district asked media specialists not to speak to the press.

The librarian says the district’s online cataloging system often glitches, and describes a chaotic weekly schedule of lesson planning and transporting teaching materials between schools while, most recently, facing a mountain of books to review — a districtwide effort under national scrutiny.

Every book in the district is being reviewed for violations of one of three Florida laws: a longstanding anti-pornography law, which state education officials say includes sexual depictions in graphic novels; the new Stop WOKE Act, which bars certain ways of teaching about race and racism; and the Parental Rights in Education law, banning instruction on gender or sexual orientation before 3rd grade and in ways that aren’t “appropriate” in higher grades.

Duval Schools cut many of its media specialists a decade ago

Only certified media specialists can approve books, according to another new law, which requires districts to publish searchable lists of materials for parents to review and contest.

Duval Schools says it's tackling the state’s new requirements with 56 media specialists, under the current vacancies — that’s less than half as many as the 125 certified media specialists in the similarly sized Pinellas County school district.

Tampa’s Hillsborough County Public Schools has nearly four times as many media specialists (222) as Duval County, with less than twice as many students.

Former media specialists who spoke with Jacksonville Today say the chaotic rollout and slow progress of the book review process is the result of a problem they’ve been raising the alarm on for years: the cutting of media specialist funding.

In 2013, then-Superintendent Nikolai Vitti took a new approach to media specialist funding by letting middle and high school principals use the funds for a testing coordinator instead. He also cut the district's elementary-school media specialist funding in half, so principals would have to use school funds if they wanted to keep a full-time media specialist, meeting minutes and news reports at the time show.

“The only possible reason for such blatant and short-sighted disregard for school libraries and the personnel who staff them is a lack of understanding of what we do and the important roles we play in student achievement and school gains,” retired media specialist Susan Santos said to the School Board in 2013, meeting minutes show.

When Jacksonville Today caught up with Santos recently, she said students’ “research skills and critical thinking skills” and their ability to spot misinformation suffers without librarians, who teach, “‘Let's verify our source, let's go find another source; let's see how these complement each other or contradict.’”

Vitti said the change freed up money for other important student services, like reading coaches.

"I believe they see more return on investment by investing in teachers and instructional coaches," Vitti told The Florida Times-Union in 2015. Now the superintendent of Detroit Public Schools, Vitti did not respond to an interview request for this story.

Former School Board member Elizabeth Andersen says competition with charter schools for the per-pupil state funding has also led to prioritizing testing scores.

“I think at the time, 2013, because we saw charters growing, there were a lot of local people that were bad mouthing public schools,” Andersen said. “You had to show the public schools were capable, and the only way to do that was with test scores, because that's the way that the system was designed.”

Under the current book review law, charter schools — which almost 19% of Duval County students attend — are largely exempt. The law says district school boards must maintain book lists and oversee selection of new materials. Charter schools are governed by independent boards.

“This is another sort of unfunded mandate. This requirement and the burden of responsibility falls onto the backs of public schools to do at whatever cost,” Andersen says. “We just are under-resourced to be able to perform it.”

Few left to review books

Gov. Ron DeSantis and the Florida Department of Education have criticized Duval County for its extensive review process, which included guidance for teachers to cover or store classroom libraries. The district says it's necessary to ensure teachers “do not have to worry about jeopardizing their career because a book may be construed to be in violation of Florida law.”

Last month, the district's head of media services also resigned amid the review, and amid reporters’ questions about her anti-LGBTQ+ comments written during a previous district book review.

Thus far, about 25,000 of the district’s roughly 1.6 million titles have been approved, according to its latest update this week. Current and former media specialists who spoke to Jacksonville Today say 1.6 million could be an inflated estimate because their online catalog often counts the same title multiple times based on edition number or paperback/hardcover differences. But, they say, due to software problems, some books are unintentionally reviewed by multiple specialists, slowing down the process.

Duval Schools wrote in an email, “Once we complete the process of fully cataloging the classroom collections, we’ll be able to answer the question about the number of titles. The ‘1.6 million’ is an estimate.”

The state’s largest teacher’s union has filed a legal challenge against the state, alleging the Florida Board of Education’s guidance to review every classroom library book — as well as books in the school library — goes beyond the scope of the law. That case is ongoing, with a hearing set for early May.

Rachael Bauman is a former Duval County media specialist who says an undervaluing of librarians at the district level trickled down to her will to do the job itself. She says she left the job, in part, because media specialists was overlooked for teacher bonuses during the COVID pandemic, despite the fact that media specialists teach classes.

“I was considered a support teacher and I was not eligible for bonuses,” Bauman says. “The year I left I did not get the COVID bonus, and then there were incentives and other bonuses that I did not get, and it was almost $6,000.”

Now, she’s teaching online college courses and has a corporate job — one that does give bonuses, she says.

In response to an inquiry from Jacksonville Today, Duval Schools said, “We are working to fill the vacancies we have for media specialists and other instructional roles. Our human resources team aggressively recruits” through various channels.

The current media specialist who spoke to Jacksonville Today on the condition of anonymity says the instability and hyper-scrutiny on the job is leading more colleagues to consider leaving — despite their love for working with the students.

“When there’s fewer and fewer of us, it makes it easier for them to say they’re going to cut libraries completely,” the media specialist says. “I love what I do and so I want to stick it out and I'd like to retire as a librarian, and I don’t know if that’s going to happen.”