When Dr. Edward Alexander Welters left Jacksonville in 1930 with his wife, Lottie, and their family, he took more than dental tools and ambition. He brought with him the formula for one of the earliest Black-owned antiseptic tooth powders in the U.S. and a burning desire to see African Americans treated with dignity, whether in the dentist’s chair, the marketplace or the voting booth.

Dr. Welters, born in Key West in 1887, was a graduate of Meharry Dental College, the leading institution for Negro dentists at the time. After establishing his practice in St. Augustine, he soon moved to Jacksonville, where he opened a modern dental office in the Masonic Temple on Broad Street. He was a proud member of Pythagoras Lodge No. 25 under the Most Worshipful Union Grand Lodge of Florida, Prince Hall Affiliated, which was headquartered at 410 Broad St., the very heart of Black enterprise in the LaVilla district.

But Welters wasn’t content to fix teeth one mouth at a time. He manufactured and sold Dr. Welters’ Antiseptic Tooth Powder from his Jacksonville office and boldly advertised it in the pages of The Crisis, the magazine published by the NAACP under the editorship of W.E.B. Du Bois.

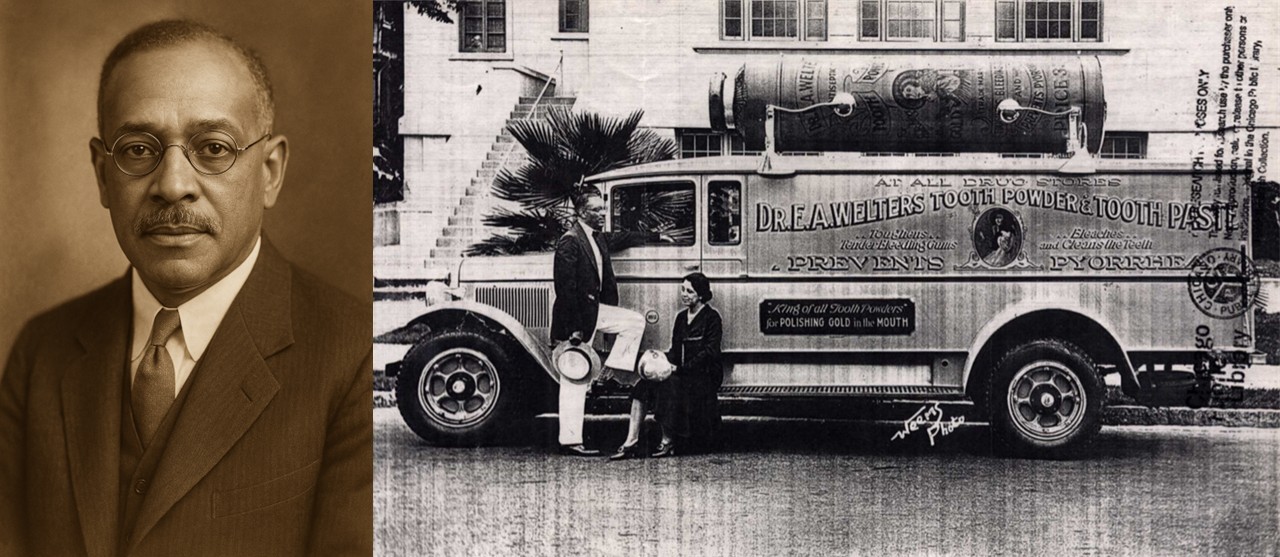

One memorable ad described the powder as “Absolutely free from grit or acid” and promised “Your gold tooth polished, your white teeth bleached” while inviting agents nationwide to help distribute it. The product quickly became a symbol of Black self-sufficiency and health consciousness. Its labeling proudly declared that it was made by the “Largest and Only Tooth Powder Manufacturing Corporation Owned and Controlled by Negroes in the United States.”

In addition to crafting the product, Welters built a remarkable promotional vehicle: a Graham Brothers delivery truck fashioned in the shape of his tooth powder can. Painted with slogans like “Prevents Decay” and “Dr. E.A. Welters Tooth Powder,” the vehicle doubled as a rolling advertisement, equipped with a public-address system that played gospel music and health announcements as it rolled through Black communities.

But as business expanded, trouble followed. Upon moving to Chicago and setting up operations in the Bronzeville district, Welters ran into problems with federal officials. In the early 1930s, the Food and Drug Administration seized multiple shipments of his product, claiming the term “antiseptic” was misleading. The government’s position was based on new food and drug regulations, but many in the Black community viewed the repeated seizures as racially motivated harassment, an attempt to silence and dismantle a successful Negro-owned business.

Welters fought what he saw as inequality with the same tenacity that had built his brand. In 1936, he filed suit against the University of Chicago Hospitals for refusing to treat him due to his race. The incident made the front page of The Chicago Defender under the headline “Jim Crow at Clinics of U. of Chicago,” rallying public support and raising questions about medical apartheid in one of America’s most progressive cities.

His activism didn’t stop in the courtroom. In 1945, Welters was elected to the Illinois House of Representatives, becoming one of the few Black men in the state Legislature at the time. During his term, he introduced and passed the Hospital Licensing Act, legislation that denied tax exemptions to hospitals that practiced racial discrimination. He also helped push through policies that prohibited segregated medical and dental schools from receiving state licensing or funding.

Throughout his life, Welters remained a committed supporter of education. He was a donor and advocate for Florida A&M University and worked to establish scholarship paths for aspiring Black dentists and medical students. In 1962, Florida A&M recognized him for his contributions to health equity and higher learning.

In his final years, Welters operated a free dental clinic from his converted mansion/factory/office on Michigan Avenue in Chicago, providing services to the underserved and unemployed. When he passed away in 1964, he was honored by Meharry Medical College for 50 years of service and remembered in the Defender as a “man who brought dignity to the dental chair and justice to the statehouse.”

Today, his papers are preserved in the Chicago History Museum, and the Masonic Temple that once housed his first office still stands in Jacksonville, testament to a man whose smile-changing powder carried with it a message far stronger than fluoride: that Black men and women were capable of building their own institutions, healing their own people, and shaping their own destinies.