It was the party of the century. It saved a building. It helped save a neighborhood. It was led by a conductor who never even worked in the rail industry. This is the story of the Station Celebration, a forgotten dispatch that rallied thousands of Jaxsons together to help save Jacksonville’s Union Terminal.

As 2024 came to a close, the University of Florida Board of Trustees Governance Committee voted to open a new graduate campus and construct the Florida Semiconductor Institute in the area surrounding the Prime F. Osborn III Convention Center.

Prior to the Convention Center’s opening in 1986, the complex was first the site of Henry Flagler’s Union Depot train station beginning in 1895 and later the Union Terminal beginning in 1919. Union Terminal was the largest railroad station in the South and at its peak handled more than 140 trains carrying 20,000 passengers each day. To support operations of such a large facility, the Jacksonville Terminal Co. (which owned the facility) employed more than 2,000 people, making it the second-largest employer in the city at the time.

Once known as the Gateway City, Jacksonville was a major railroad center for more than 50 years. The Jacksonville Terminal Co. was a partnership made up of the rail lines that served the terminal complex, all of which still loom large in today’s transportation world: Florida East Coast Railway (started by Standard Oil principal Henry Flagler), Southern Railway (now Norfolk Southern Railway) and the Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Co. (now CSX Transportation). All trains going to or coming from South Florida would originate from this facility, and therefore the growth of modern-day Florida occurred because of the commerce that took place at this entryway to the state.

Rail transportation to and from this site was indeed the lynchpin of Henry Flagler’s plan to develop southern Florida as a major resort area at the turn of the century. Travelers would arrive from all around the world to Florida via Union Terminal, where they would be greeted by real estate agents, attorneys and bankers all eager to sell land or company stock for residential, hoteling and commercial developments throughout Florida. Every president between Warren G. Harding and Richard Nixon passed through the terminal. In the 1930s, porters from the Jacksonville Terminal formed the Jacksonville Red Caps, an all-Black baseball team named after the red hats the porters wore. The Red Caps went on to play in the Negro Major Leagues, making them the first major league sports team in Florida.

The 1919 facility was designed by New York architect Kenneth Murchison. He borrowed freely from the design on New York’s Penn Station, which itself had been modeled after the Roman Baths of Caracalla. Union Terminal was and still is Jacksonville’s greatest example of the Neo-Classical Revival architectural style, both in scale and substance. The entrance is marked with 14 unfluted and colossal Doric columns made from sandstone that physically face Downtown. The 75-foot soaring, barrel-vaulted ceiling of the ticketing hall and waiting room is complemented by eight thermal windows that provide clerestory lighting from above. The building is constructed of reinforced concrete with a limestone veneer, with copious amounts of Tennessee granite and marble throughout. In all, the building contained more than 150 tons of ornamental iron. Passengers could even gawk at a live alligator, which lived in a terrarium within the concourse.

Passenger rail operations had begun to wane during the latter half of the 20th century, with the construction of interstate highways and commercial aviation becoming a preferred means of leisure travel. Freight rail travel was substantially more profitable than passenger rail service, and rail operators turned to the federal government to deregulate the industry and drop the requirement to carry not-as-profitable passengers across the country.

With the passage of the Rail Passenger Service Act of 1970, freight carriers would no longer be required to operate passenger rail service, and the National Railroad Passenger Corp. (aka Amtrak) was formed. When Amtrak took over all private railroad passenger train operations in 1971, three-quarters of the country’s passenger rail services were eliminated in a single day. By 1974, only four passenger trains were regularly serving Jacksonville. That same year Amtrak moved its operations to a cheaply constructed and no-frills passenger platform and parking lot on the Northside, eliminating Amtrak’s obligation to maintain the once-grand Union Terminal. By Christmas 1974, the splendid terminal facility was home to only a couple of office tenants and a warehouse for a paint distributor.

Stretching almost 18 acres, the old train complex was eyed as the perfect site to be leveled and redeveloped for a new use. Around the same time the Skyway was envisioned to connect the Gateway Mall to Downtown traversing primarily down Main Street, the Jacksonville Transportation Authority had also begun to seek federal grant funding to acquire and ultimately tear down the Union Terminal complex in order to build a massive bus maintenance facility. This plan would have used taxpayer dollars to destroy a beloved landmark and reduce a large section of a struggling LaVilla to little more than a parking lot for buses.

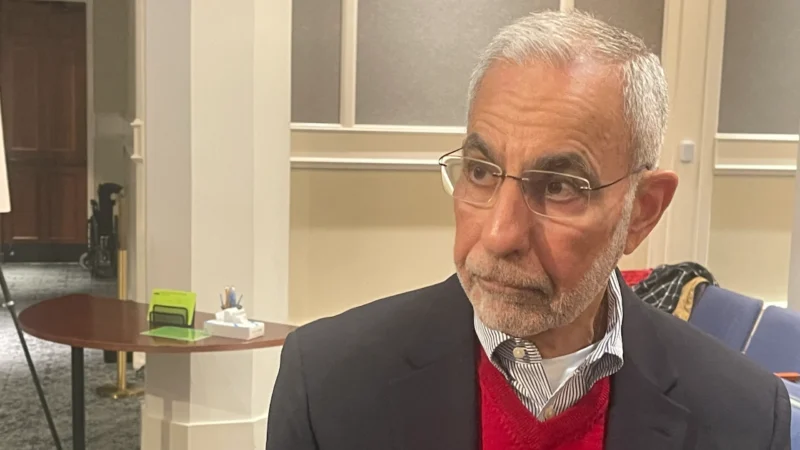

That’s when a charismatic fellow brimming with the unabashed energy of man who had just turned 30 decided it was time to save this iconic structure. His name was Dr. Wayne Wood, a young optometrist who moved to Jacksonville from Texas to take up work with his uncle. He was a respected professional with a captivating allure and quick wit. But underneath the white lab coat, Wood was stirred by a hippie-esque altruism, convinced the world could be saved through divergent thinking and the occasional sit-in.

The first step would be to list the property on the National Register of Historic Places. That process began in 1976. Before JTA sought funding for a bus maintenance yard, the Jacksonville Terminal Co. had preliminary explorations about converting the older station into a “gaslight district” along the lines of Underground Atlanta. When the costs for such an endeavor ballooned to more than $4 million, and development partners could not commit to raising the necessary capital, the JTA’s bus yard plan appeared to be the easiest route to dispose of the property. Fearing restrictions on redevelopment options, the Jacksonville Terminal Co. initially opposed historic designation.

These photos from the Jax Fire Museum show Flagler’s original Union Depot in 1900 (above), how this portion looked in 1975 having been integrated into the 1919 Terminal Station redevelopment (below) and how most of the remaining Union Depot complex was destroyed in a 1979 fire.

Wood would schedule a visit with Prime Osborn, the president of Seaboard Coast Line. Prime was a war hero who distinguished himself in Saipan and Iwo Jima before earning a law degree and beginning a career in the railroad industry. As general counsel of Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Co., he orchestrated the merger with Seaboard Air Line in 1967 to form Seaboard Coast Line Railroad Co.

Wood remembers, “His office resembled a grand church, and when he arose to shake my hand he looked like an absolute giant in my mind.” Unshaken, he smiled, looked Osborn square in the eyes and said, “I’d like to borrow your train station for a few months to throw a few parties and try to save it.” The rail executive burst out laughing and exclaimed, “Son, you’d need a million dollars in insurance to pull something off like that.” Three days later, Wood returned to the SCL legal office with insurance in hand.

Now very much a train conductor in his own right, Wood and a fervent army of volunteers sprang into action to patch up the four buildings that made up the bulk of the complex. After years of Amtrak stewardship, a general lack of maintenance and an abrupt abandonment, there was plenty to clean up.

During the 1960’s, a drop ceiling had been installed in the main terminal and covered with acoustic tile to reduce noise and install a more economical air conditioning system that would not have to cool such a large area. A deal was struck with Burkhalter Wrecking Co. whereas Burkhalter would remove the drop ceiling and once again expose the cavernous 75-foot terminal ceilings, and in exchange they would keep the steel trestles and keep whatever other valuable scrap was removed during the restoration process.

The abandoned station was regularly patrolled by security. However, vagrants had infiltrated most of the complex, setting small fires and stripping out wiring, copper and ornamental pieces. Given that the electrical system had been rendered useless, Paxon Electrical stepped up to temporarily rewire the venue so that it could accommodate a few raucous parties.

The Sermac Co. thoroughly cleaned more than a decade of grime from the walls, while waxing and polishing marble floors to the same condition which once greeted passengers when the station opened in 1919.

Wood then used his connections to enlist the services of the Probationer’s Residence Program, a state-run program for non-violent offenders who were required to conduct community service to satisfy their sentencing requirements. Working alongside dozens of RAP volunteers, this rag-tag group of sinners and saints refurbished wooden benches, cleaned stained glass ceilings with a toothbrush, restored railroad signs, patched cracks in the plaster walls and repaired baggage carts once left in the train station to rust and rot.

At least twice, vagrants broke into the building, requiring even more volunteer hours to clean up what had already been scrubbed just days prior. In all, several hundred volunteers and more than three dozen businesses donated time, money and services to temporarily restore the terminal into a state worthy of hosting a monumental gala.

During this time, the Jacksonville Terminal Co. relented and agreed to designate the building for historic protection status, provided that unnecessary and historically insignificant portions of the property were excluded. The historic designation effectively barred JTA from receiving federal funds to tear down the buildings in order to construct its bus maintenance facility. The JTC pivoted to sell JEA the former Railroad Express Agency rail terminal facility along Myrtle Avenue, once the largest express terminal in the country that closed in 1975 as air freight and tractor trailers took on more delivery of express packages (such as FedEx and UPS). The remnants of the REA Terminal were mostly demolished to construct the JTA bus maintenance yards, which are still in operation today as the JTA Myrtle Avenue Operations Campus.

Top: the former REA Terminal in the 1950’s. Bottom: the JTA Myrtle Avenue Operations Campus in 2025

By November 1977, the first of three parties would be held called Station Celebrations. That first Station Celebration featured the acclaimed 16-piece orchestra of Jimmy Glenn. The Silver Meteor and Red Cap bars sold champagne for the debutantes and nickel beers for the bacchanals, often interchanged. Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton silent films were shown against the grand, soaring concourse walls. A live-action casino dubbed the Golden Spike was erected, offering chances to win fabulous prizes. Smaller rooms throughout the facility offered themed dance parties: one a disco complete with a mesmerizing light show and another a honky-tonk in a room with stained glass ceilings.

While Jacksonville had hosted the annual Florida Georgia football game since 1933, better known as the World’s Largest Outdoor Cocktail party, the magnitude of the Station Celebration party was simply without precedent. Over 7,000 partiers crammed into the facility. Today, lawyers and fire marshals would never allow that size of a crowd to congregate inside, but this was the 1970s and people clearly didn’t need much of an excuse to look the other way. Despite a truck load of kegs being consumed that night, the place was so packed no one could fall over from drunkenness. It was indeed the party of the century. Wood recalls fondly, “People were lined up down Bay Street nearly a half hour before our doors even opened. This was during a time when few dared to be seen in the area after dark.”

Wood convinced manager Peter Lyons of Victoria Station to stage the Great Barbecue Rib Promotion, selling barbecue ribs to hungry party goers that first night, with all profits benefiting RAP. Peter didn’t quite correctly estimate the insatiable appetites of those packed in the terminal. Although a huge smoker was located outside the building, twice throughout the evening, Victoria Station would run out of ribs. Complicating matters was a logistical nightmare as the pitmasters couldn’t quite figure out how to carry huge trays of ribs while simultaneously seeking to navigate through the masses of people that packed the terminal standing shoulder-to-shoulder. In less than two hours, over 900 slabs of ribs were gone. They would have been sold out in less than an hour, if not for those logistical obstacles.

RAP was then the city’s largest preservation organization, and the parties were staged to show potential developers that there was substantial interest in saving the buildings and finding them new life. Buying a $10 admission ticket was a way of declaring, “Yes, we want this building saved.” RAP raised nearly $50,000 that first night.

The Station Celebration was the birth of a new spirit in Jacksonville that went far beyond a single building. People who attended came from every part of the Jacksonville populace, making it a true community event. At the time, it would not be exaggerating to say that at least half of Jacksonville had once arrived or departed from the train station. That common bond stirred those from all walks of life to come together and save the buildings.

The success of the parties proved that creative ideas could bring the city together to accomplish things once thought impossible. As bulldozers had begun to level the historic fabric of Downtown throughout the 1960’s and 1970’s, it was clear that many Jaxsons were looking for a new direction that was intent on restoring the architectural gems and cultural institutions that had once made Jacksonville a unique place.

With proceeds earned from the Station Celebrations held in 1977, 1978 and again in 1981, Jerry Spinks would establish a revolving loan fund for RAP to acquire distressed homes. With volunteers and donated services, RAP would rehabilitate and re-sell the properties, with profits going back into the fund for additional acquisitions. More than a dozen structures were saved because of the loan fund during a time when the Riverside and Avondale neighborhoods were struggling to attract investment to rehabilitate nearly century-old properties. Now, the neighborhoods are home to some of the most expensive pieces of real estate in the city.

To think, a small spark in the neighborhood’s turnaround would ignite because of the pioneering spirits and money raised from the preservation-minded adventurers that staged the Station Celebrations.

While attending the party, several Lee High School alumni led by Lee McIlvaine and Bob Howard got together to propose redeveloping the terminal into a multi-million dollar hotel, restaurant and entertainment complex modeled after the Chattanooga Choo-Choo. Closed in 1970, the Chattanooga Terminal was renovated in 1973 and re-opened as the Chattanooga Choo Choo Hilton and Entertainment Complex. McIlvaine, who passed away in 2009 at the age of 92, was a legendary businessman and philanthropist in Jacksonville. He purchased the property from JTC and continued to stabilize the buildings after a 1979 fire that damaged nearly all remaining portions of the original Flagler Union Depot buildings. Based upon the repairs required after the fire, the redevelopment plans had to take a back seat in order to save the rest of the remaining structures.

While that plan never left the station, a former Charter Company executive and Station Celebration-party goer Steve Wilson was inspired to take up the helm. Wilson introduced Mayor Jake Godbold to representatives from the Rouse Company about opening a festival marketplace in Jacksonville. Wilson thought the terminal would have been perfect for the festival marketplace concept, or perhaps a large park-n-ride facility to feed riders to/from an entertainment complex nearby.

The Chamber of Commerce, City Council, the Downtown Development Authority and the Mayor’s office just so happened to be exploring the need to build a modern convention center to attract tourists to a struggling Downtown at the same time. Clearly the winds of change were sweeping through Downtown, and opportunity was abounded. Shortly after the third and final Station Celebration, Wilson placed the Union Terminal under a purchase contract in 1981. He had preliminary conversations with Rouse about converting the facility into a festival marketplace. Rouse, though, preferred a smaller site closer to the central business district’s existing retail stores and office workers.

Convinced that the large size of the terminal complex and its direct access to the interstate highway would be the perfect site for a convention center, Wilson cobbled together a who’s-who of local executives such as Prime Osborn, Charlie Tower, Martin Stein, William Nash, Wesley Paxon, W.W. Gay and Jack Demetree to execute his purchase agreement. For two years the group negotiated to enter into a public-private partnership with the city of Jacksonville to redevelop the main terminal building and construct a modern, 265,000-square-foot convention center along the former rail spurs behind the terminal. After the convention center finally broke ground, Rouse began working with Godbold to acquire a riverfront site to eventually construct the Jacksonville Landing.

On October 17, 1986, the new convention center opened, followed by a wildly successful four-month run of the Ramses II traveling show, the largest collection of ancient Egyptian artifacts. Ramses II was a coup for Jacksonville, as it was only exhibited in four cities across North America.

The convention center was named for Prime Osborn, who passed away the year prior, the man who once thought Wayne Wood was crazy to save, and who later put up his own money to help restore it.

Today, funding is in place for the city of Jacksonville to explore restoring the Prime Osborn as a central rail station and bring new passenger rail connections to Jacksonville. While the terminal building and nearby railroad trackage could see new life through an old use, the University of Florida will eventually be using portions of the existing convention center to construct later phases of a graduate campus and accompanying residential structures.

If trains ever do come back to the terminal, perhaps it would be fitting to name any new passenger facilities for the man that had the eye for it all: Dr. Wayne Wood, the train conductor who never once worked as a railman.