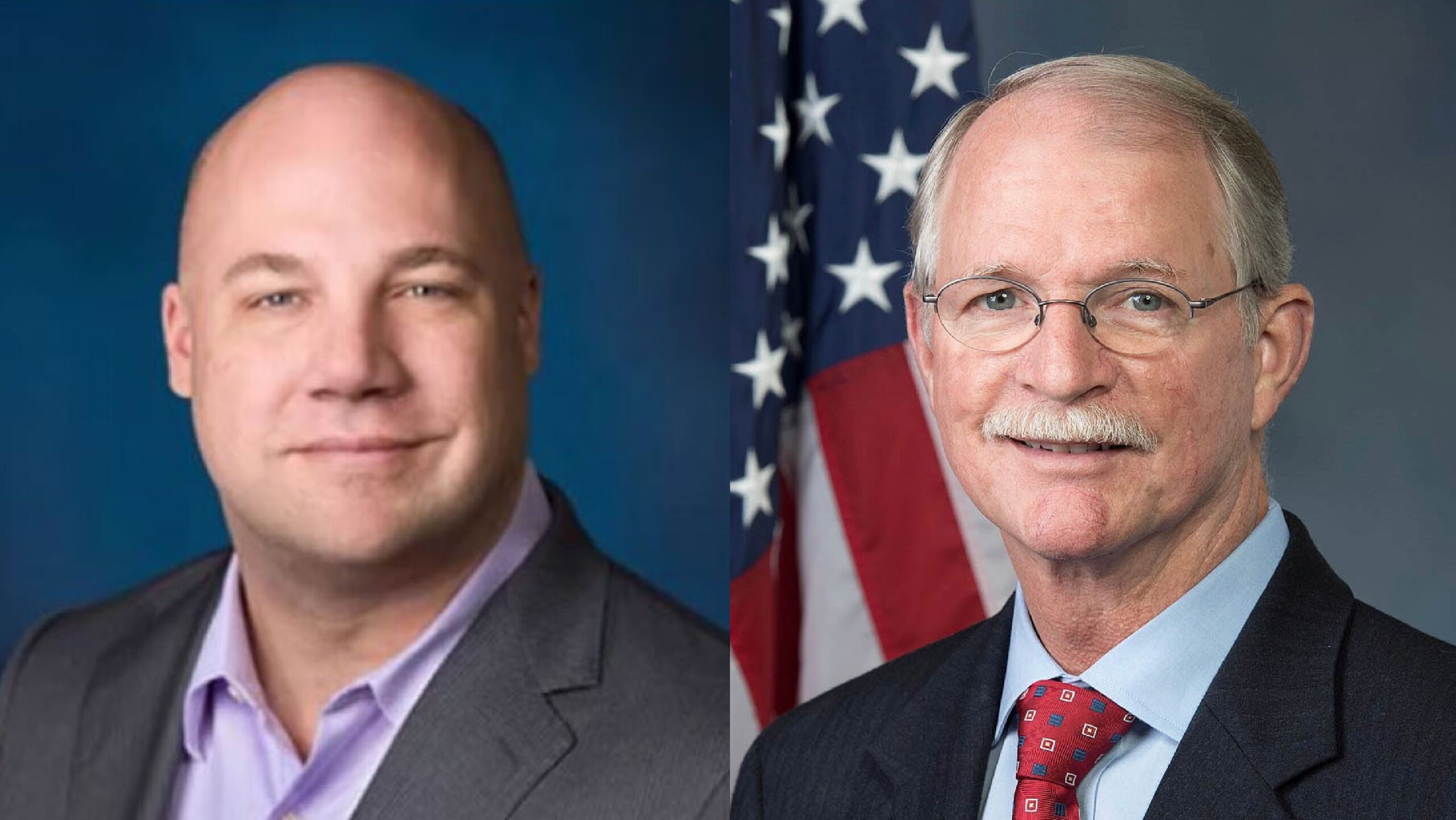

Kent Stermon, the influential Republican donor who was under criminal investigation when he died last month, was issued five separate badges giving him access to Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office buildings, starting in 2013 under former sheriff and current Congressman John Rutherford.

Records obtained by Jacksonville Today show Rutherford was the first of three Republican sheriffs to allow Stermon access to JSO buildings.

About 400 people not employed by the city have been granted access to the Sheriff’s Office over the past decade. Most are contractors and interns, but Stermon was one of nine classified as part of the “sheriff’s circle.”

Stermon used his badges to access multiple sheriff’s office substations, JSO aviation facilities and investigative areas. He had access, for example, to one area the Sheriff’s Office has refused to disclose under a Florida law that protects “surveillance techniques or procedures.”

The Sheriff’s Office has released conflicting records that hide exactly how Stermon used his cards, and has not explained why a non-employee member of the community had such widespread access – including late at night.

Rep. Rutherford, R-FL4, did not respond to multiple requests for comment this week.

Civilian access to JSO

Stermon was a friend of Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, an influential Republican donor and the president of the Jacksonville-area defense contractor Total Military Management. Stermon donated at least $28,000 to Rutherford’s U.S. House races since 2016, campaign finance records show.

Stermon died by apparent suicide in early December, while under “active investigation” by the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office. The department has not disclosed the nature of that investigation, but the State Attorney’s Office told Jacksonville Today this week that it is assisting.

Multiple groups of people outside the Sheriff’s Office have ID cards allowing them access to JSO buildings, according to the department’s public information officer, Tami Dash. Records obtained by Jacksonville Today show 194 contractors, 128 interns, 12 city and police Federal Credit Union representatives, seven volunteers and nine people classified as part of the “sheriff’s circle” received badges at some point.

Others with “sheriff’s circle” badge access include Ryan Backmann, founder of the nonprofit Project: Cold Case; local beverage CEO Earl Benton; and former Atlantic Beach Mayor Mitch Reeves. The Sheriff’s Office says current Sheriff T.K. Waters has since discontinued “special access to individuals outside of the need for official business.”

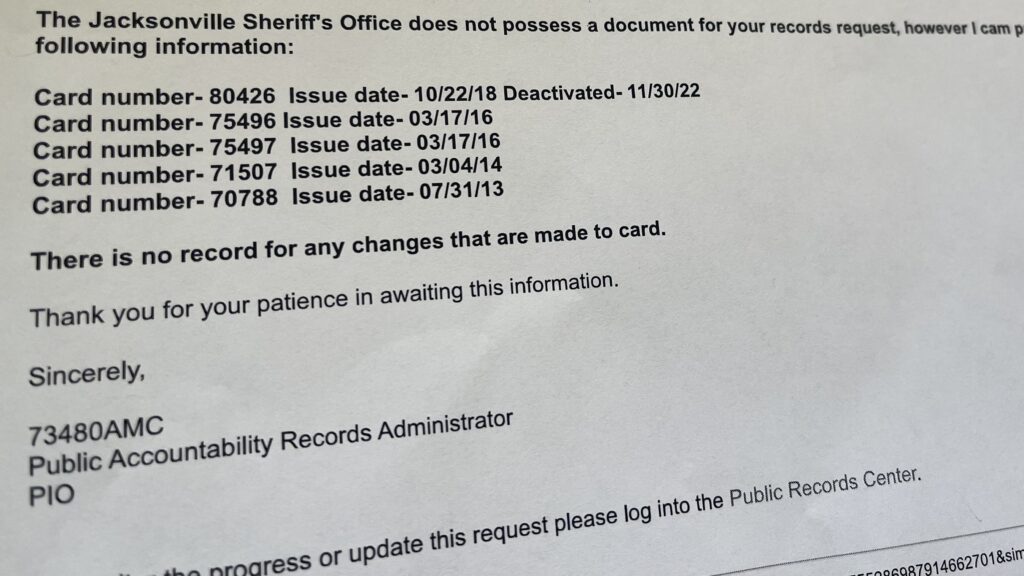

When Jacksonville Today asked why Stermon had five separate access cards, JSO public information officer Christian Hancock said: “The specific reason for the issuance of multiple cards over the 8+ year duration is not documented. But this could have been for any number of reasons, to include having been lost, stolen, damaged, updating a picture, etc.” He added that each prior card would have been “disabled, confiscated, and destroyed (if applicable) upon receiving a new one.”

The Sheriff’s Office’s security policies say someone could be denied a JSO badge for “any pending felony criminal or theft case.” Stermon’s most recently issued of the five access cards was granted Nov. 22, 2018, under former Sheriff Mike Williams. It was deactivated on Nov. 30, 2022 – the day after officers filed a police report in their investigation of Stermon.

JSO reports show that the agency was notified Nov. 29 of a “potential crime” involving Stermon. The incident is reported as having occurred Nov. 18, though the Sheriff’s Office withheld the location under a legal provision that protects ongoing investigations.

The name of the officer leading the investigation is also concealed under a provision in Florida law that protects “undercover personnel.”

Late-night visits

After Stermon’s death last month, the sheriff’s office released five years’ worth of access logs at the request of Jacksonville Today. They showed that Stermon used his badges more than 700 times since 2017 and on at least 25 separate dates in 2022. (The Sheriff’s Office had previously told Jacksonville Today those records did not exist, but now says the missing logs were due to a “software issue.”)

Portions of the records are blacked out – or “redacted” – to conceal exactly what buildings Stermon accessed. But they show he entered JSO buildings after normal business hours on at least 11 dates since 2019. The buildings included four sheriff substations, the K-9 unit and the JSO aviation building. Twice in 2022, he entered JSO buildings after 9 p.m, and once at almost 1 a.m. in 2021.

Normal business hours for the Police Memorial Building are 8 a.m. to 5 p.m, according to Sheriff’s Office policies. The Police Memorial Building has a 24-hour gym that could account for Stermon’s late night visits, but he did not have a release of liability form on file, JSO said, responding to a Jacksonville Today records request. All employees or guests must complete that form to use the gym.

Inconsistent records policies from JSO

The Sheriff’s Office has been inconsistent in explaining why it is withholding information about nearly 700 doors Stermon accessed over five years.

In most cases, the information was redacted from public records based on a Florida law that protects building security or fire safety system plans. But in other cases, the office cited a provision that protects police departments from revealing surveillance techniques or procedures.

Both explanations conflict with JSO’s own actions last summer in response to another records request from Jacksonville Today. At that time, JSO provided a log of badge swipes by former Sheriff Williams. The same category that is blacked out in the Stermon logs – door “device description” – is public in the Williams document, which shows which days Wiliams went to the gym and accessed the front gate, side gate, elevators and various other doors.

JSO has not yet responded to Jacksonville Today’s questions about why it treated information about Stermon, a private citizen, differently from information about Williams.