Tuesday’s primary election will likely begin to close the book on a three-decade run of Black congressional representation in Jacksonville, as the region’s “minority access district,” Congressional District 5 currently represented by Democrat Al Lawson, becomes history.

Two Black candidates, Democrats Tony Hill and LaShonda “LJ” Holloway, are running to replace Lawson, but election prognosticators consider the newly drawn District 4, which includes part of Lawson’s old district, to be “solid Republican,” and former Republican state Sen. Aaron Bean is seen as the frontrunner in his primary against Erick Aguilar and Jon Chuba.

A federal lawsuit asserts that the Legislature’s recent redistricting discriminated against Black voters when it took away Lawson’s district and another minority access district in Central Florida.

In interviews with Jacksonville Today leading up to the election , Black Jacksonville voters in the newly drawn district were split — while some agree with the lawsuit’s assertion that redistricting was unfair to Black voters, others welcome the opportunity for new ideas in Washington.

District demographics

Dennis Wade has lived in Duval County for 22 years, including the past decade in Lawson’s CD5. After voting early at the Duval County Supervisor of Elections Office on Friday, he called Florida’s redistricting process “racist.”

“What they did is they were trying to reduce the impact of the Black vote in the district,” Wade says.

New North Florida districts were drawn by Gov. Ron DeSantis’ office and approved in a special legislative session this year after the governor vetoed a map that would have preserved Lawson’s district. DeSantis’ directive to the Legislature was to “have North Florida drawn in a race neutral manner. We are not going to have a 200-mile gerrymander that divvies up people based on the color of their skin.”

Lawson called the governor’s map a disservice to Florida voters.

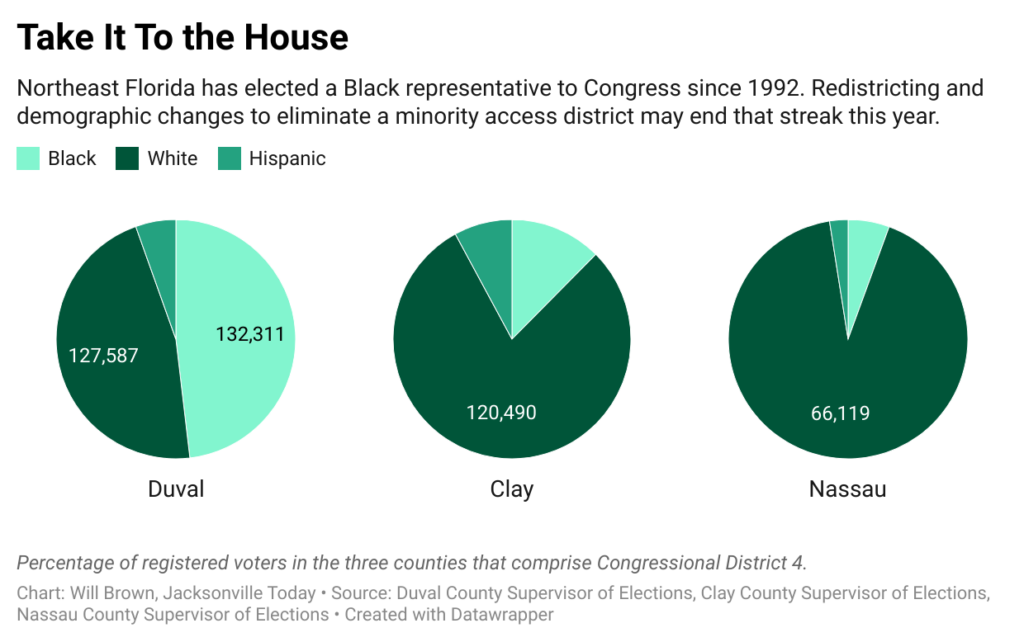

The district Lawson represented was 46.4% Black, while Black voters make up just 22.9% of those registered in the new Congressional District 4 — of the 534,538 voters in Clay, Nassau and the portion of Duval County, 58.8% are white and 5.4% are Hispanic.

“The Republican party does not represent the values of African Americans and other minorities,” says Wade, who voted for Hill in the primary.

Angela Lee, one of the scores of people who voted early Saturday at the Legends Community Center in Northwest Jacksonville, agrees. Lee is a lifelong Sherwood resident who has served as a poll worker for more than 20 years.

The prospect of not being represented by Lawson is “not a happy thought” for her. She says she personally witnessed Lawson’s talking to college students about the importance of the democratic process.

“A lot of people won’t admit he did a lot for the Northside. He didn’t just show up at barbecues. I have seen him do a lot for our community,” Lee says.

Finding food in a desert

Last year, Lawson helped secure $2 million in federal funding to help White Harvest Farms & Market build a farm processing and packaging center. The 10-acre urban farm on Moncrief Road is operated by the Clara White Mission with the intent of reducing food insecurity.

Clara White Mission CEO Ju’Coby Pittman, a member of Jacksonville City Council, told Jacksonville Today in May that it’s vital for communities to have an opportunity to vote for people who culturally understand the regions they represent.

Lawson, Pittman believes, fit that mold.

“We want the same quality of life for residents along (the) Moncrief and Myrtle Avenue area as everyone else in this community,” Pittman said.

A welcome change for some

Shamari Lewis agrees with Pittman: Northwest Jacksonville needs more economic development and investment — but he disagrees that a minority access district represented by a Democrat is the way to get it.

“What the district needs is a progressive mindset that is centered in economic development, proper zoning, proper civil engineering and planning with an eye and a mind for 50 years from now,” says Lewis, president of the Duval County Coalition of Black Republicans.

The group of approximately 50 people works with a volunteer network of another 50, Lewis says.

He asserts the new districts double Jacksonville’s representation in Congress. His thinking goes that minority access districts — congressional districts with enough minority voters to elect a candidate of their choice — can limit Black representation if they concentrate Black voting power too much in those districts while diluting it in surrounding ones — known in court cases as “packing.”

“After decades of doing this, neighborhoods have issues that are not being addressed,” Lewis says. “The Democrats who have been elected in these areas after decades — some people brought money back and did good things — but it hasn’t been robust enough. It’s time for change.”

Lewis has lived most of his life in Duval County, where today nearly 80% of registered Black voters are Democrats. His first foray into politics was serving as a canvasser for Corrine Brown’s campaign when he was a teenager. He remembers the “Corrine Delivers” signs that were all throughout Northwest Jacksonville.

“We, as Black people, cannot allow any party — not the Republican party, not the Democrat party — to take our votes for granted,” Lewis says.

The Black Republicans coalition is not endorsing a candidate in the primary.

Seeing both sides

Jacksonville Urban League President Richard Danford says it’s not enough to have a minority access district, or to elect Black people. Danford says the new district needs someone who is more focused on their constituents than on the next office. Danford says Lawson was good at this — in April, Lawson presented the Urban League with a $2 million check to help fund a veterans’ center in Newtown — but Danford believes the size of his district neutered his effectiveness.

James Whitfield agrees. Whitfield lives in Mandarin, but he spends a lot of time in the new congressional district, volunteering on the board of the MaliVai Washington Foundation and watching his son play football at Wesconnett Park.

Whitfield believes the more geographically compact district and a representative who is based in Northeast Florida will benefit Jacksonville.

“It will bring visibility and the resources needed to empower youth, to take care of our elderly and just to get resources in our community,” Whitfield says.

This spring, Lawson touted his ability to bring $14.8 million in Community Project Funding back to the district. However, $10.3 million of those dollars went to other communities across his nearly 200-mile North Florida district.

Earlier this month, the A. Philip Randolph Institute for Law, Race, Social Justice and Economic Policy at Edward Waters University held a Jacksonville voter summit to help educate the public about the candidates vying to replace Lawson.

One of the attendees, Marcia Ellison of Newtown, said any downside of losing Lawson is outweighed by the potential to elect someone with fresh ideas and methods to bring development, resources and opportunities to the district.

“I would like to see someone put a store here,” Ellison says. “Let me be able to buy an apple, an egg, a loaf of bread. All I can get around here is processed food.”

While she says Republicans “don’t care for people who are not rich,” she also believes Lawson “hasn’t done anything for Jacksonville.”

For her, the person and the party are not as important as what they do once they get to Washington.

“I will listen to what you have to say. A lot of people say things,” Ellison said. “Show me something you have done.”