In many states, flood-prone areas tend to be where lower income people live. The state of Florida, on the other hand, has some of its highest-value development along the coasts, which are increasingly threatened by rising seas, more intense hurricanes and more frequent and severe floods. Despite these threats — and because of them — beachfront living will grow increasingly expensive to maintain.

Eventually, many coastal residents and businesses will leave for higher and drier ground.

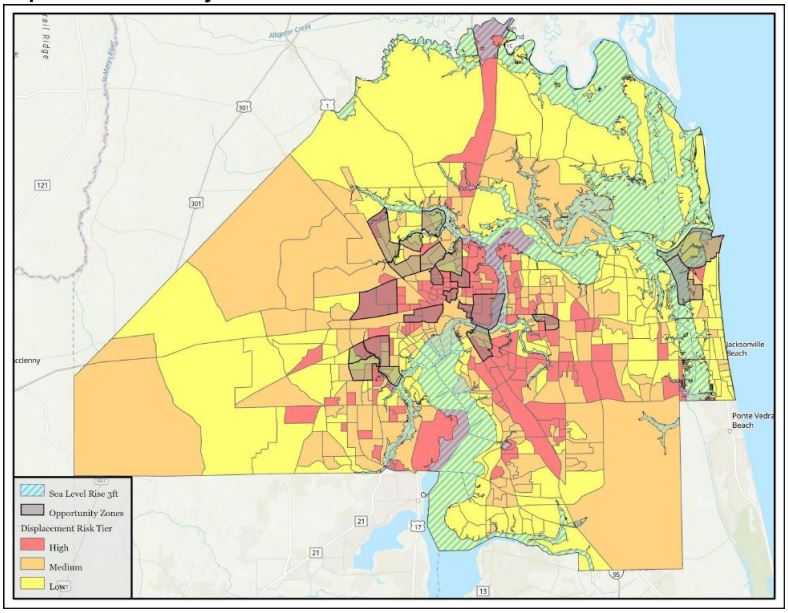

And as higher-elevation neighborhoods are redeveloped on account of the influx of coastal refugees, longtime residents there will increasingly face pressure to leave, either voluntarily (selling their homes or businesses) or involuntarily (eviction or increased rent). This “climate gentrification” is already starting to play out in Miami, and researchers at Florida State University say parts of Jacksonville will likely experience it in the coming decades, in places like Newtown, Mixontown, Durkeeville and the Eastside.

“I think this conundrum is really hard for us to wrap our heads around,” says William Butler, an associate professor in the Department of Urban and Regional Planning at FSU and lead author of the recent study on climate gentrification in Florida. “It’s really hard to accept the reality that at a certain point, many of our coastal areas that are currently densely populated and highly developed will not be tenable. We won’t be able to stay. It’s sort of an existential crisis.”

Quick and sharp reductions in global fossil fuel emissions would help humanity avoid the worst impacts of climate change. However, limiting global warming to 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5 degrees Celsius), as was called for under the 2015 Paris climate accord, appears out of reach given our current trajectory, according to the latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The average global temperature is likely to rise by 1.5 degrees Celsius between 2030 and 2052 if emissions continue at their current rate, meaning Florida must prepare for the impacts of climate change — or “build resilience” — now.

Florida and many of its local governments have begun to invest in climate resilience in recent years, but Butler says no community is adequately addressing climate gentrification. Up to this point, most resilience projects in Florida have been focused on protecting areas with the highest economic values.

“I think that our orientation to both development and to thinking about things from a cost-benefit analysis approach has the potential to ignore equity and justice in a very substantial way,” he says. “And it’ll lead us to protect the areas that have the highest wealth, highest income, highest economic activity, which are those areas that have the greatest capacity to do so on their own, and to ignore areas that have the least wealth, the least economic activity, who also have the least capacity to protect themselves.”

The FSU report highlights four main recommendations for communities like Jacksonville that will likely deal with climate gentrification:

- Incorporate resilience into all development decisions

- Encourage and protect affordable housing development

- Educate and provide tools to residents and advocacy groups

- Develop a collaborative and holistic approach to addressing the risks posed by climate change

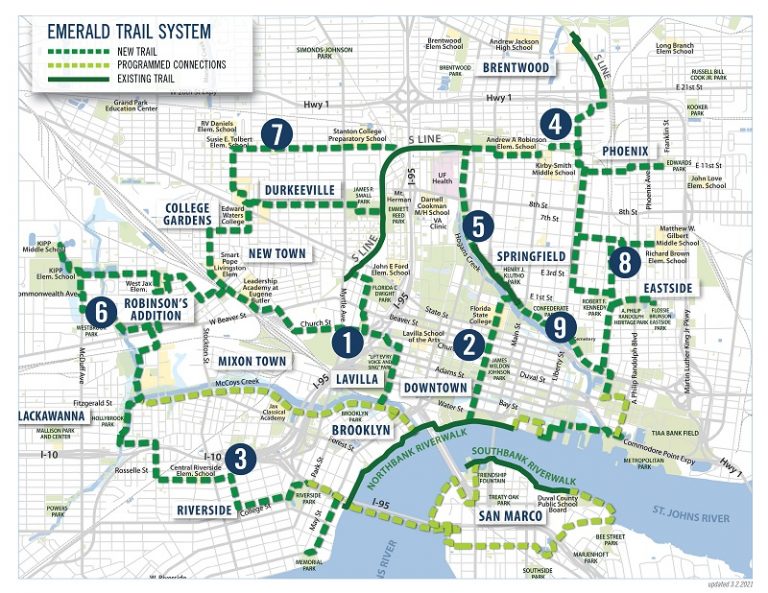

Included in that holistic approach, the study says, are projects already underway across the state that could help offset climate gentrification, including Jacksonville’s Emerald Trail — a 30-mile network of bicycle and pedestrian trails that will eventually connect 14 urban core neighborhoods to each other, Downtown, the St. Johns River and parks. The project also includes the ecological restoration of McCoys and Hogans creeks.

“The trail alone is adding green space, trees, and helping with stormwater runoff. The creek restorations are reducing flooding, they’re increasing water quality, they’re creating habitat for fish and wildlife and they’re providing access for recreation that doesn’t exist today,” says Kay Ehas, CEO of Groundwork Jacksonville, the nonprofit that’s coordinating the trail’s construction.

The benefits of the Emerald Trail will be concentrated in neighborhoods that have historically been economically disadvantaged, she says. “We’re going through majority Black, majority low-to-moderate income neighborhoods with an average poverty level of 35%.”

Although the trail is held up as an example of how to increase the quality of life in poor neighborhoods, its arrival stokes fear about another kind of displacement.

“With the trail coming, a lot of people are very concerned about losing their homes, especially people who live along McCoys Creek,” says Padrica Mendez, a North Riverside Community Development Corporation board member.

“It’s what we call green gentrification,” Butler says, “doing environmentally friendly investments in an area that beautifies it, and then all of a sudden you’ve got a whole group of people who weren’t thinking about living and developing in an area all of a sudden are interested.”

That’s part of why Groundwork Jacksonville has been engaging with the future trail’s neighbors throughout planning and development.

“They are not just there to help us with the trail and to get us on board with the trail, but they’re actually there to help people stay in their homes, people who want to remain in that neighborhood,” Mendez says. “At first, they were met with a lot of opposition, but they definitely have the buy-in. I know they definitely have my vote and the North Riverside Community Development Board’s vote.”

Butler says there’s no evidence of land value or neighborhood changes that are being driven by climate gentrification in Jacksonville yet, so the city has time to prepare. But it will take more than just the Emerald Trail to stave off the risk.

“Everybody is going to have to get on the same page – which means elected officials, developers and everybody else – about how we are going to do this in an equitable way so that people don’t get kicked out,” Ehas says. “If you look at the urban core, there is a lot of vacant land and abandoned buildings. So there’s room for new people coming in with higher levels of income, to me, without having to displace the people that are currently there.”

Jacksonville’s Chief Resilience Officer Anne Coglianese, who’s been tasked with preparing the city for the impacts of climate change, has read the FSU report on climate gentrification and spoken with the researchers. She says their concerns will factor into her resilience plans.

“To me, this [report] is signaling what could happen if policymakers aren’t paying attention. And the good news here in Jacksonville is that we absolutely are. And there’s a lot that we have in the works right now that I think will feed into avoiding some of the worst-case scenarios that come out of this report,” Coglianese says. “Currently, we are developing a comprehensive resilience strategy for the city of Jacksonville…and housing is absolutely going to need to be a piece of that.”

Keeping housing affordable

Florida’s biggest cities have a significant shortage of affordable and available rental homes, according to the National Low Income Housing Coalition. Jacksonville has fewer than 13,000 affordable rental homes available to the more than 40,000 low-income families who need them.

“If you have a child at a public school, if you go to the doctor, if you go to a restaurant, if you go to an entertainment park, you’re bound to meet someone who relies on affordable housing to sustain their lives,” says Laurie Schoeman, the director for climate and sustainability at Enterprise Community Partners, an affordable housing organization. “Everyone who accesses affordable housing plays a key role in our communities, and without that housing available there is nowhere to support folks if there’s an emergency or crisis.”

To help address Florida’s ongoing affordable housing crisis and the threats posed by climate change, Enterprise Community Partners launched the Keep Safe Florida program this year. The program, which started last year as a pilot in Miami, offers free tools and resources to help affordable-housing owners and operators deal with climate change and natural disasters. At the moment, Keep Safe Florida is working with owners and operators in Miami, Tampa and Orlando, and Schoeman says she’d be thrilled to see people in Jacksonville and other communities participate.

“Florida is very much on the frontlines of the climate crisis, the struggle to preserve and protect communities from these risks,” Schoeman says. “There is no state better positioned to be at the lead and at the helm of trying to undo the gentrification, to reduce displacement, than Florida.”