In Wes Anderson’s new film, The French Dispatch, Julian Cadazio (a huckster of substantial means played by Adrien Brody) is trying to convince his rich uncle to back his latest scheme: investing in modern art.

Cadazio, while doing a stint in prison, has stumbled upon the work of Moses Rosenthaler, a hyper-macho, mentally ill and enormously talented artist played by Benicio Del Toro, who is doing time for a brutal murder.

“Why is this good?” Cadazio’s uncle asks when shown a large-scale abstract work, which Rosenthaler has covered in emotive strokes of flesh-colored paint.

“It isn’t good. Wrong idea,” Cadazio responds.

“One way to tell if a modern artist actually knows what he’s doing is to get him to paint you a horse or a flower or a sinking battleship or something that’s actually supposed to look like the thing it’s actually supposed to look like,” Cadazio continues before producing a charcoal drawing of a bird, executed with pinpoint accuracy and distinctive style. “The point is: he could paint this, beautifully, if he wanted to.”

Cadazio then points to Rosenthaler’s abstract piece. “But he thinks this is better.”

The vignette is classic Wes Anderson absurdism, yes. But Brody’s character gets at something elemental about modern art: Context is important. Cadazio believes that if Rosenthaler’s art could be shown in an institutional setting, if viewers knew of his unique background, they’d be convinced of his genius and purchase his paintings.

Richard Heipp could paint anything he wanted, near perfectly. But, over the course of his nearly 50-year career as a professor of art and art history at the University of Florida and a working artist whose paintings have been exhibited across the country, including several times in Jacksonville, Heipp’s work has overwhelmingly been interested in context.

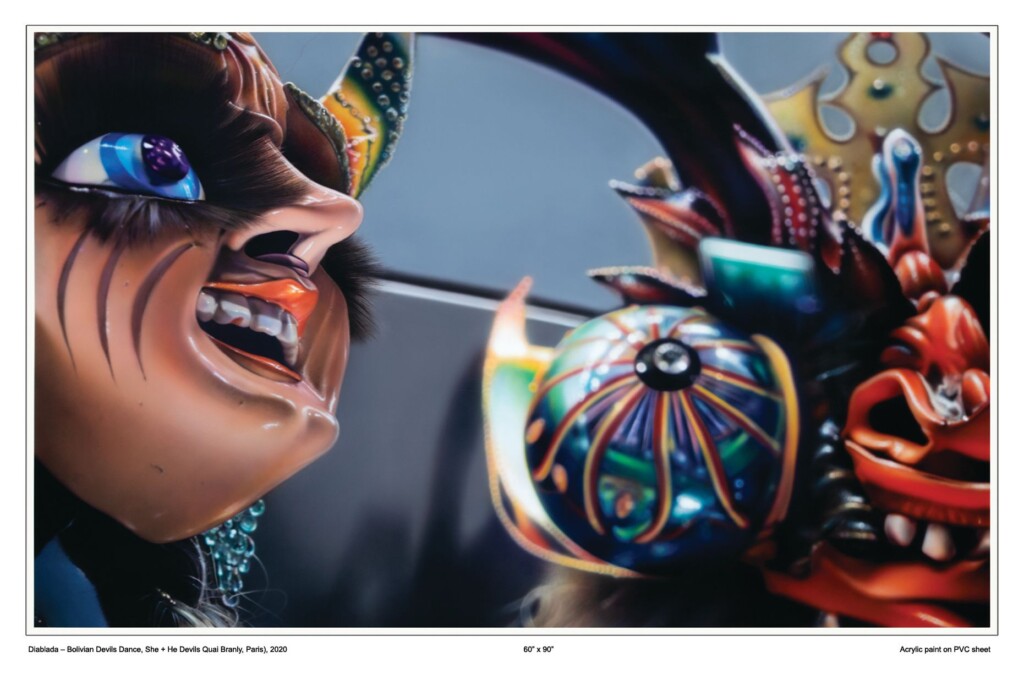

Take the piece “Diablada – Dolian Devil’s Dance, She + He Devils,” which depicts artifacts as they appear in an exhibit at Thee Musée du Quai Branly in Paris. A vibrant and menacing mask conveyed in sharp focus flanks a blearily rendered ornate orb of purple, gold and turquoise. Measuring nearly 6 feet tall and more than 8 feet wide, the image is impressive in scale and enthrallingly colorful. Awe-inspiring, on its own, sure. But especially so if you know the image was produced not by a modern inkjet printer, but rather by the meticulous hands of a human being.

By its most reductive description, Heipp’s art is about art. Heipp puts it even more succinctly: “I just copy s***.”

“I try very hard to make [my paintings] look like photographs and I include all the tropes of photography in them,” says Heipp. “If you slow down and look, I’m hoping some kind of alchemy happens. Like from lead to gold, I hope the realization that it’s not a photograph elicits a new response to the painting.”

Heipp’s photorealistic paintings are executed with baffling precision. But Heipp is less interested in dazzling the viewer. By painting something impressive, even spectacular, Heipp hopes to engage the viewer more deeply. In many ways, the image itself is kind of a trick.

“I almost wish it was more of a trick,” Heipp laughs. An art critic once reviewed a show of his paintings, referring to the works as photographs throughout the article. “I don’t want it to be like a magic trick where, once you know how it’s done, you only admire the skill of executing the trick.”

Is Heipp’s work good? By any technical or aesthetic measure the answer is yes. But that’s not the point. Wrong idea.

“I want the response to be not, ‘Oh, how skillful,’” he says. “But I’d really want [the viewer] to ask, ‘Why?’ Or ‘How does this affect me differently knowing that the artist had to make a decision about every little mark on the canvas.’”

Beginning Friday, January 28, “Diablada” will be on view at Jacksonville contemporary art gallery Florida Mining as part of Devils and Saints, an exhibition of more than 40 works by Heipp. Most of the work for Devils and Saints was produced in the last two years, a period of time which coincided with Heipp’s gradual retirement from teaching at UF.

Before he takes on a painting, Heipp takes dozens, sometimes hundreds, of photographs, bending light, shifting focus, altering the perspective however he can. He then paints what he sees in the photographs. By its most reductive description, Heipp’s art is about art. Heipp puts it even more succinctly: “I just copy s***.”

The pieces in Devils and Saints span several recent series, including Culture Masks and Museum Studies, in which Heipp paints artifacts and art from actual museum exhibits to explore how systems of display change how a viewer interprets an object’s meaning.

Much of the work in Devils and Saints depicts religious artifacts, shiny, ostentatious objects reflecting light in unique ways, such as Catholic reliquaries, that have been of interest to the artist for much of his career.

“Lots of reflections, bobbles––those are things that I like to paint,” Heipp says. “But I’m interested in objects that cultures have placed spiritual value upon, objects with mystical powers.”

The show also includes multiple works from Heipp’s Reflection on Beuys series. Using photographs Heipp captured of photographs of Fluxus pioneer Joseph Beuys that were temporarily on display at the Dia art museum in Beacon, New York, the black-and-white images Heipp painted for the series are as disorienting as that description makes them sound.

Courtesy of the artist

In “Reflection on Beuys #7: Arena — w/Tools, (DIA),” we see a framed photograph of Beuys at work in some kind of warehouse space, bending over a grid of tiles, an assortment of objects — a tripod, shovels and other hand-tools —surrounding him. We also see the reflection in the frame of another industrial space (the Dia), as well as the photographer (Heipp), camera aimed just off center.

The effect of “#7” is one of bewilderment or altered-reality. It’s a multi-layered optical illusion.

“I was blown away by these photographs,” Heipp says of seeing the Beuys images on view at the Dia. “But I was also blown away by how the museum space merged with the space of the photographs — the illusion of the space; the illusion of the reflection of the space [the photos] were in; the illusion of the stuff on the photographs themselves, which included stains and scratches. All of it merged into one thing. That was the magic.”

While he admits to not being a Beuys expert, Heipp says he found the artist to be an intriguing subject. “He was kind of a shaman and a mythical figure” he says, pointing to Bueys’ own myth-making which included a made-up story about flying a fighter plane for the German army in WWII, being shot down and then nursed back to health by Eastern European farmers — none of which was, apparently, true (or at least verified).

“I saw in these images of Beuys — this disorienting merger of spaces — as a metaphor for the mystery of the artist,” he says. “And I also connected with this notion of myself being a first-generation German immigrant.”

Heipp grew up in Cleveland, Ohio. The son of factory workers, Heipp struggled in school, due in large part to undiagnosed dyslexia, as well as an ocular disorder called Strabismus. Heipp loved drawing from an early age. And he believes his Strabismus, which has the effect of flattening three-dimensional images, made him a better drawer.

Heipp’s first love was music. He played in bands, but realized early on that he wasn’t going to be a rock star. In part to avoid the Vietnam draft, Heipp enrolled in an architectural drafting program at a community college, where he took an art class. He then spent a year at Ohio State University before earning a scholarship to the revered Cleveland Institute of Art.

It was across the street from the school, at the Museum of Contemporary Art Cleveland that he first encountered the photorealist works of painters Chuck Close and Don Eddy.

“It knocked my socks off,” Heipp says of the exhibit. This was the early 1970s and photorealism was having a moment. After researching Close’s techniques, he ripped a photograph out of a National Geographic magazine, stretched a canvas, grabbed some oil paints and started copying what he saw in the image. A few years later, Heipp was invited to the Blossom Art Intensive summer program at Kent State University, where he worked alongside Eddy.

“At the time, I was making oil paintings that were trying to mimic airbrush,” Heipp says of his naivete in photorealism. “Don Eddy said, ‘Why are you trying so hard to make it look like an airbrush?” After Heipp told Eddy he didn’t have the slightest idea how to use an airbrush, Eddy instructed him, “Buy one. Plug it in. Pour paint. Point it at the canvas. The rest is practice.”

“And that’s what I’ve been doing for the last 50 years,” says Heipp, who paints almost exclusively in airbrush.

For an artist who relies on state-of-the-art tools for making work that is interested in how technology changes the way artwork is consumed, Heipp’s career has spanned a fertile five decades. High-resolution camera phones now threaten to make the DSLR, which long ago subsumed the film camera, obsolete. Heipp has kept pace, embracing new technologies like digital scanners to render new inspiration for his paintings.

Meanwhile, smartphones and social media relentlessly inundate the public with imagery, changing the way viewers engage with reality.

“I used to tell my students, if you lived in the early 17th Century, in the time of Rembrandt, you’d be lucky if you saw 100 images in your lifetime,” Heipp says. “I’ve always thought that how we view art is an interesting barometer of our culture. It’s always changing.”

Heipp finds the term photorealism to be misleading, arguing much like David Hockney has that photography is not a more truthful representation of reality. “The term photorealism makes the analogy that the photograph is capturing reality,” he says. “It’s actually capturing a single-lens, mechanical version. That’s not realistic. It’s really an index of what’s there.”

Devils and Saints will be Florida Mining’s fifth exhibition since the gallery reopened in 2020. Gallery founder Steve Williams says Heipp’s art fits with the mission of Florida Mining — which, as an exhibition space, focuses on the work of artists working in the American Southeast — and also expands upon what the gallery has exhibited to date.

“This show is really about the process of Richard’s work, which we’ve been following for more than 20 years,” Williams says. “His work seems more relevant now than ever.”

Gallery manager James Meadows believes the ability of Heipp’s imagery to place the viewer within its complex and often disorienting layers gives the paintings a powerful resonance. “You see [Heipp] in the image. You see multiple layers of glass, there’s four and five layers. And still you get to find your placement inside the piece. I find that’s what makes really powerful artwork — when you’re able to find your voice inside that work.”

The Florida Mining show will mark Heipp’s sixth exhibition since 2018, a run that was bookended by a retrospective at the Polk Museum of Art in Lakeland, Florida, and last year’s retrospective at the University Gallery at UF.

“I loved teaching, but If I had my choice I’d be in the studio all the time,” he says of his productivity of late.

The pace of technological change is not likely to decelerate any time soon. And with a society primed to take up real estate in a metaverse, where some will likely visit a showcase of non-fungible token art at a museum rendered in virtual reality, the lenses through which we view imagery will undoubtedly change. In other words: More fertile ground for Heipp — new perspectives, new settings, new realities for the artist to “copy.”

An opening reception for Richard Heipp: Devils and Saints will be held on Friday, January 28, from 6-8 p.m. at Florida Mining Gallery; 5300 Shad Road, Jacksonville 32257. The gallery is open to the public Monday through Friday from 10 a.m.-5 p.m. or by appointment.