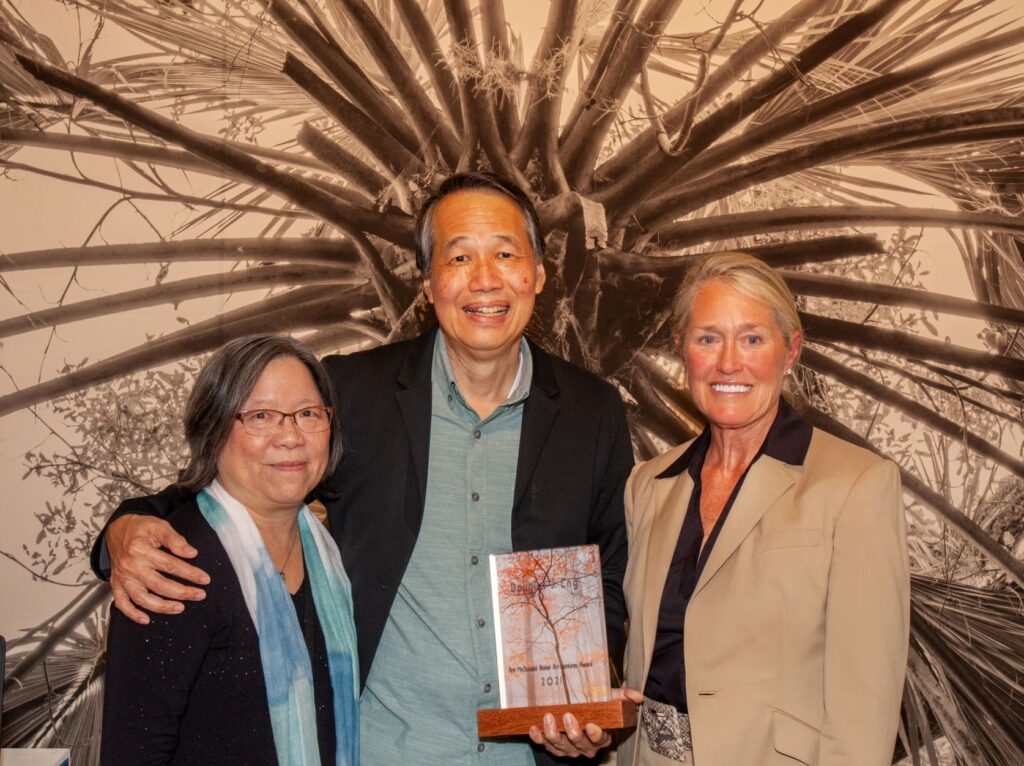

Through his art, Jacksonville photographer Doug Eng is trying to help people gain more of an appreciation for the natural environment — and ultimately, of how their own actions are affecting it.

Eng recently won the Ann McDonald Baker Art Ventures Award from the Community Foundation for Northeast Florida, which includes an unrestricted grant worth $10,000. Work from the Jacksonville native’s career is on display at the Museum of Contemporary Art Jacksonville through January 2, 2022.

Credit: Laird/Blac Palm, Inc.

As soon as you make it to the top floor of MOCA, where his exhibit, Structure of Nature | Nature of Structure, is on display, it’s obvious that Eng has a bit of an obsession: trees.

Eng worked as an engineer for decades, so for him the appeal has a lot to do with form and structure.

“The tree always embodied the characteristics of something that I always seem to be interested in,” he told me.

The exhibit is divided into four distinct sections. The first, which you see as you come up the stairs, is immersive: a wide forested landscape divided into segments that hang from the ceiling, as the sounds of nature quietly permeate from a hidden speaker above. The second area focuses on the simple beauty found in nature, from portraits of individual trees to landscapes of foggy sunrises over black water creeks. The third section is all about form and structure and how patterns emerge in nature, many of which are mirrored in cityscapes.

Credit: MOCA

The final part of the exhibit, which features Eng’s most recent work, resonated with me the most. Here, Eng aims to show the viewer what’s threatening the natural environment: people.

“This is sort of what I’m working on now, these types of issues,” he says. “I wanted people to remember it. That was the last thing they saw, so hopefully it would set something in their mind.”

Credit: MOCA

In this portion of the exhibit, Eng draws the viewer’s attention to three environmental issues: stronger hurricanes, the loss of eastern hemlocks and the Rodman Dam, for which environmentalists are calling to be removed.

Photos from Eng’s Fractured Forests series show the aftermath of Hurricane Michael, a devastating Category 5 storm that made landfall near Mexico Beach, Florida, in October of 2018. As global temperatures rise due to climate change, ocean temperatures are warming too, and warmer waters fuel stronger storms. Meanwhile, rising air temperatures lead to more evaporation, which in turn leads to more precipitation, increasing rainfall during those storms. These factors, combined with sea level rise (another symptom of climate change), also contribute to more intense flooding.

Credit: Doug Eng

In Witness to Extinction, Eng chronicles the loss of hemlock forests in the Appalachian Mountains. In the 1950s, an invasive species made its ways into these forests: the wooly adelgid. The insect is native to Japan and was brought to the U.S. unintentionally with ornamental Japanese hemlocks. Since it was introduced, the tiny invasive insect has spread into at least 17 states, from the Smoky Mountains to southern Maine, and poses a serious threat to the sustainability of eastern hemlocks.

Credit: Doug Eng

The Drowned Forest series hits a bit closer to home. Through these images, Eng explores the thousands of acres of cypress floodplain forest that were submerged when a 16-mile reservoir became part of the Cross Florida Barge Canal, construction of which was halted in 1971. The Rodman Reservoir, as it’s called, still exists today and is lowered for four months every four years to clear surface vegetation. Eng’s photos were taken during one of these drawdowns, revealing a haunting landscape of thousands of dead tree stumps.

For years, people have called for the Rodman (or Kirkpatrick) Dam to be breached. Doing so would restore the Ocklawaha River (a tributary of the St. Johns River), returning an estimated 150 million gallons a day of freshwater flow to the St. Johns. This could help mitigate saltwater intrusion in the St. Johns River, which is largely being driven by sea level rise and the ongoing river dredging.

Credit: Doug Eng

Eng wants his work to be part of the solution to environmental issues that are important to him.

“I’m at the point where the only thing I think I can do is: A) support the organizations that are actually out there on the ground doing things, and B) through the photography and imagery, the installations, try to raise awareness,” he explains. “I felt it was important, if it’s an issue that’s important to me, to actually get that in front of someone and not really try to direct someone as to what to do, but to go, ‘Hey, here’s a situation that I found,’ and just present it to them.”

Credit: Doug Eng

Eng says other photographs are part of the exhibit because, quite simply, he finds them visually appealing — art for art’s sake. But while all of Eng’s pieces are undeniably beautiful, the benefits of the trees and natural spaces he’s photographed far outweigh their aesthetic value — they literally sustain us. Trees produce the oxygen we need to survive, wetlands reduce flooding and forests absorb pollutants (including carbon dioxide, the main greenhouse gas driving climate change).

The subjects of his photographs are worth your time and attention — they are fine art. And if that’s the case, are those subjects not also worth protecting? Eng hopes he’ll inspire his audience to seek them out once they leave the museum and “participate” in nature.

“It’s one thing reading about it and going, ‘Oh yeah, I love nature. And I’ve got all these books and I watch these videos.’ But man, get yourself out into it,” he said. “Because when you participate in it and you build that connection with that place — and especially if it’s your home — then if something threatens it, or something happens to it, you’re going to have that connection and you’re going to do something.”

If you go:

MOCA, at 333 N. Laura St., is open 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. Tuesday through Saturdays and from noon to 5 p.m. on Sundays. The museum is closed on Mondays, and will also be closed on Dec. 24, 25 and 31, as well as Jan. 1, for the holidays. Guests are required to wear a mask. More information here.