At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and during the ensuing economic slowdown, Jacksonville virtually shut down. Businesses shuttered their doors and most who were able to started working from home. That meant far fewer internal combustion engine vehicles were being driven, leading to massive reductions in air pollution and noticeably cleaner air.

“There was definitely less traffic,” said Veronica Glover, a lifelong resident of Jacksonville’s Urban Core and the executive director of the Sister Hermana Foundation, a non-profit that helps families fighting cancer. The only time Glover noticed any serious traffic was during the food giveaway events that she helped organize or at COVID-19 testing sites across the city.

Credit: Veronica Glover

What Glover witnessed was happening all across the globe, but as people and industries returned to their routine use of cars and trucks, air quality worsened again. That’s because the largest contributor to carbon emissions in the U.S. is transportation — contributing to 29% of national emissions. And 76% of emissions in the transportation sector come from the fossil fuel-burning engines in our cars, trains, trucks and buses.

Electric vehicles present a solution for reducing this substantial share of harmful pollutants. Experts say electrification of trucks and cars would be an essential step toward canceling out America’s yearly greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. Often called “net zero,” such an elimination of heat-trapping emissions would also require deep investments in solar and wind generation and battery storage, possibly nuclear power, and an overhaul of transmission lines nationally.

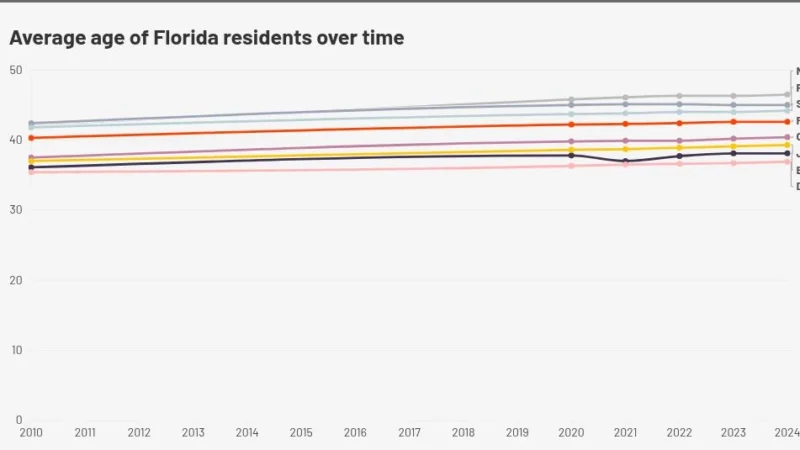

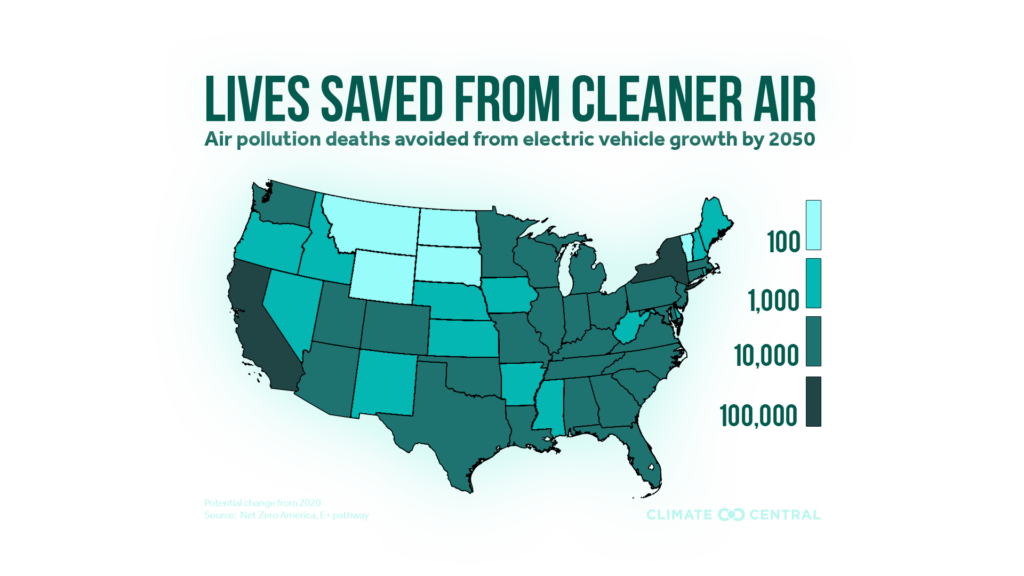

Princeton University’s Net Zero America program has been researching scenarios that could see the U.S. reach net zero by 2050. Under a scenario with an aggressive approach to electrifying vehicles, one that would see sales of electric vehicles outnumber sales of gas guzzlers within a decade, they estimate Florida could avoid nearly 10,000 premature deaths by 2050 caused by diseases from tailpipe pollution.

The benefits wouldn’t just be felt in frontline communities like Glover’s. Air quality across the entire state would improve if internal combustion engines were replaced with electric vehicles.

Putting all those electric vehicles on the roads would mean more than just building and buying them, though. A raft of infrastructure overhauls would be required, including scaling up installation of chargers and changes to utilities’ electrical transmission strategies.

Florida officials last year prepared a roadmap that could help the state achieve such a daunting task. The plan included everything from adapting transportation infrastructure to advancing electrified mobility and electrifying disaster preparedness.

The Republican-controlled legislature passed its first piece of climate legislation in 2020. With the next legislative session beginning in January, Advanced Energy Economy policy lead and Clermont City Councilman Ebo Entsuah is paying close attention to what policymakers bring forward.

“Especially in a state where we do see a number of natural disasters, it’ll be important for our legislators to get together and put out some of these recommendations from the floor, from the electric vehicle roadmap,” Entsuah said.

Credit: Sharkshock, Shutterstock

Multi-billion-dollar boost

Florida has the third-highest number of new EV charging stations added between 2017 and 2021, behind California and New York. At 58,160, Florida also has the second highest number of registered EVs in the country.

Dory Larsen, the Electric Transportation Program Manager for the Southern Alliance for Clean Energy, says thanks to booming EV sales, utility investment and charging deployment, Florida is poised to lead the EV market across the Southeast. To meet that demand, an additional economic boost could come from EV manufacturing in the state, she says.

“We found that in Florida, if all of the cars, trucks, and buses were electric today, Florida would have an extra $12.5 billion circulating through the state’s economy, annually,” said Larsen. A SACE report found that in 2019, the state and consumers spent $27.6 billion on gas and diesel, while fully electric transportation would have cost only $17.2 billion.

The time it takes to move from combustion engines to electric motors will have a significant effect on curbing overall greenhouse gas emissions. EVs would need to dominate American auto sales by the end of this decade for the U.S. to successfully decarbonize by 2050, helping it meet the goals of the Paris Climate Agreement and avoid the most catastrophic potential levels of climate change.

The federal administration is taking steps toward net zero planning as President Biden has called for 50% of passenger vehicle and light truck sales in 2030 to be zero-emission vehicles. On Thursday, the federal administration released the newest framework of their $1.75 trillion Build Back Better plan, which it is trying to push through Congress.

The new framework includes a $555 billion commitment to curbing carbon emissions, with a focus on making clean energy cheaper through tax credits. The legislation also specifies electrifying transit systems to improve air quality, reducing consumer costs of EVs manufactured in the U.S. and directing clean energy jobs towards lower-income communities.

Credit: Bill Bortzfield, WJCT News

Electric vehicles in the River City

Convincing drivers to switch technologies for the sake of air quality could be a tough proposition. Fleet purchasers wield a lot more consumer influence, and the rental car industry will play a critical role in the widespread adoption of electric vehicles. Tesla’s new $4.2 billion deal with Hertz signals a shift in the way the rental car industry is responding to consumers’ growing sustainability demands.

For individual consumers, fuel savings can be a draw, helping to start to replace some of the internal combustion engines on the roads with cleaner-running electric vehicles.

Electric vehicle fueling costs per household can be 50% to 75% lower than for gasoline-fueled vehicles. A 2020 U.S. Department of Energy study found that in Florida, an EV driver’s lifetime fuel costs are an average $7,000 cheaper than for drivers of fossil-fueled vehicles.

That cost-effectiveness is what won Jacksonville resident Erik Gonzalez over. “After having done some research into EVs, and Tesla in particular, I was really just impressed by not just the performance aspect, but the reliability and the cost of maintenance,” he said.

Gonzalez just invested in his first Tesla. He gets about 285 miles out of a full charge and has driven about 6,000 miles. “That equates to a cost savings of about $1,100 so far, just in fuel savings,” he said. Gonzalez also recently signed up for a new incentive program for EV owners that JEA launched in October.

The rebate can shave nearly $100 a year off the electric bill and offset some of the cost of installing an electric charger.

“This is a win-win for the utility and for the EV owners that get approximately 2,000 miles of free driving every year they enroll in the program,” said Dave McKee, JEA’s program manager of electrification.

Gonzalez is one of hundreds who have signed up for the rebate, which is part of JEA’s larger Drive Electric program. JEA and the federal government also offer incentives for individuals and companies that want to install electric vehicle charging stations, on top of up to a $7,500 federal tax credit for buying new electric and hybrid vehicles.

Many Jacksonville residents considering EVs may also be concerned about what their city utility’s energy mix means for their personal carbon footprint. JEA is still very dependent on fossil fuels. Last year the utility got just 1% of its energy from renewable sources and this year is expected to be very similar.

JEA, however, has a stated goal of getting 30% of its energy from carbon-neutral sources by the end of this decade. It’s working through the logistics of how to get there.

Credit: Bill Bortzfield, WJCT News

“We are going to know more, probably, in a year and half to say what our forward plan is, and we’ll have a much better understanding of how renewables play into our mix,” said Vicki Nichols, JEA director of customer solutions, market and development.

Jacksonville is not unique. Electric vehicles still only make up 1% of passenger cars worldwide, but many of the world’s biggest automakers are investing in manufacturing EVs, from Ford to Toyota to Volkswagen, in a range of price points and styles.

JEA is also working with Jacksonville car dealers on educating shoppers about the benefits of electric vehicles, including at Tom Bush Volkswagen in Arlington.

“Volkswagen’s really getting into electric vehicles in a big way. They’re developing a whole fleet of charging stations across the country, and they just launched the ID.4 this last spring, and it’s selling so well. We’re really excited about this vehicle,” said Megan Del Pizzo, vice president of Tom Bush Volkswagen.

In addition to price, one of the most common concerns Del Pizzo and her colleagues hear from customers interested in EVs has to do with finding charging stations. According to Del Pizzo, that’s pretty much a non-issue in the River City.

“The amount of chargers we have in Jacksonville now, you really don’t need the range anxiety that a lot of people have when they’re driving an electric car, because there are chargers everywhere: at dealerships, workplaces, at the (St. Johns) Town Center,” she said.

Duval’s high ratio of charging stations per driver is due, in part, to a relatively low number of EV vehicles on Jacksonville’s roads.

“We benefited from entities like Town Center mall coming out with large charging banks… but less than 1% of our market right now is EVs,” said Nichols with JEA. “But a year from now, who knows? We may be behind. So we’re committed to keeping up with the market.”

As EVs grow in popularity, gas stations throughout Jacksonville and elsewhere could install charging stations to benefit from the transition to a majority electric transportation sector. But a new Florida law, signed by Gov. Ron DeSantis in June, prohibits local officials from requiring gas stations to install electric vehicle chargers.

“It really is taking the power out of the hands of the municipalities and the counties and preventing them from hitting those 100% clean energy goals,” said Ebo Entsuah, the state policy lead at AEE. State legislators’ shying away from clean-energy legislation and gas industries’ lobbying against local sustainable policies doesn’t help. “It definitely can stall a bit,” Entsuah said.

Credit: Marshall Ritzel, AP Photo

‘A triple burden’

Exposure to air pollution increases the chance that people will end up in the hospital, and if they have respiratory or cardiovascular diseases like COPD, stroke, lung cancer or asthma, it lowers their chance of surviving them. That means where you live within Jacksonville can actually be a matter of life and death.

“In low and middle income areas of cities, where historically, highways and roads tend to have been built in… in those areas where there’s a lot more car traffic and transportation traffic, we see a higher increased risk or higher increased prevalence of these diseases,” said Scott Helgeson, a pulmonologist at Jacksonville’s Mayo Clinic.

Air pollution disproportionately affects those living near busy freeways and congested roadways, in neighborhoods that typically have larger portions of Black and Latinx residents, partly because of racist historical housing practices such as redlining. These frontline communities also tend to live close to power plants or other industrial facilities, which compounds the poor air quality.

“There’s a triple burden,” said Marianne Hatzopoulou, a professor in engineering at the University of Toronto and head of the school’s transportation and air quality research group. “Not only are disadvantaged populations experiencing the highest levels of air pollution, but they are also the ones that are generating the least amount of emissions from transportation in a day,” she said.

Hatzopoulou says a growing body of evidence linking air pollution exposure to social disadvantage should be taken into account when local and state governments evaluate transportation decisions.

“What we want is the benefits of these policies to actually accrue to the people who are exposed to the highest level of air pollution,” Hatzopoulou said.

For nearly two years, researchers tracked air quality disparities between low-income neighborhoods of color and high-income white neighborhoods in Jacksonville and more than 50 other U.S. cities. The recently published study, co-authored by University of Virginia atmospheric chemist Sally Pusede, focused on levels of NO2, or nitrogen dioxide — an air pollutant released from fossil fuels that can cause and exacerbate chronic health problems like asthma.

In Jacksonville, people of color living in low-income neighborhoods breathe air containing nearly a quarter more NO2 than non-Hispanic whites living in high-income areas.

That same study also compared diesel NO2 emissions on weekends with weekdays, finding that a drop in heavy trucking on weekends led to pollution cuts of more than 60% on average, with frontline communities benefiting the most.

“This is another piece of evidence that says to policymakers that these trucks are really important, to control the emissions of diesel trucks,” said Pusede. “People should be paying attention to the equity dimensions of these vehicles. That is the most important part.”

Throughout her life, Jacksonville resident Veronica Glover has had to watch her friends and family suffer through terrible illnesses. Her mother has COPD and is a breast cancer survivor, her husband died from colon cancer and her grandmother died from lung cancer. Glover, who herself is a breast cancer survivor, worries that pollution from vehicles and industrial sources is contributing to the prevalence of these diseases in her neighborhood just northeast of Downtown.

“Inhaling that same type of toxin over and over and over again is definitely not good for our community,” she said. While Glover tries to help residents deal with the effects of pollution, she hopes city leaders and other policymakers start pursuing electrification strategies that will help communities like hers breathe cleaner air.

“It would definitely impact and increase our numbers, in saving lives,” she said.

This story was produced through a collaboration involving WJXT, ADAPT from WJCT Public Media, and Climate Central, a nonadvocacy science and news group.