On the evening of Wednesday, March 11, 2020 — the day before the Florida Department of Health confirmed Duval County’s first coronavirus case — a small crowd gathered inside Taliaferro Hall at St. John’s Cathedral in downtown Jacksonville to hear a local scientist talk about climate change.

“I think your faith could be a powerful motivator on this issue,” Adam Rosenblatt, an assistant professor of biology at the University of North Florida, said from the pulpit. Rosenblatt — who runs a lab at UNF that studies the effect of environmental change on plants, animals and ecosystems, with a current focus on alligator eggs — was invited to speak at the Episcopal church by its relatively new community outreach and social networking group called Green Spirits, which is devoted to spreading the word about environmental issues, including climate change.

Faith-based efforts like Green Spirits are increasingly popping up around the country as Christians — many of them young — start to push back against the skepticism of climate science that has taken root in their communities.

Rosenblatt, a cofounder of the Citizens’ Climate Lobby Jacksonville Chapter, connects climate change to scripture in his church talk tonight. He uses biblical passages that highlight environmental stewardship — sometimes referred to as “creation care” — including Genesis 2:15: “Then the Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to tend and keep it.”

This is the founding tenet of Green Spirits. “We will take action to learn about, to protect, and to renew God’s earth and all who call it home,” the group’s vision statement reads.

“The Bible says in book one, chapter one that humans have responsibility over every living thing on this earth. In the last book of the Bible, Revelation, it talks about how God will destroy those who destroy the Earth,” says Katharine Hayhoe, a prominent climate scientist, professor of political science at Texas Tech University and author of A Climate for Change: Global Warming Facts for Faith-Based Decisions, which she wrote with her husband Andrew Farley, an evangelical pastor.

Hayhoe, an evangelical Christian whose parents were missionaries, said she actually became a climate scientist because of her faith.

“Climate change, unchecked, will not mean the end of this planet. It’s not about saving the earth. It’s about saving human civilization, and especially those who are already suffering impacts that don’t have the voice to tell us or to advocate for change. And so, because of that, I truly feel like this is what God has called me to do,” she said.

In a TED talk that has now been seen by millions, Hayhoe makes the case that the most important thing any individual can do to fight climate change is talk about it. But, she says, people shouldn’t spread the good word — so to speak — until they have a solid baseline of knowledge.

That’s where organizations like St. John’s Cathedral’s Green Spirits come in. Like Hayhoe, founder JoAnn Tredennick believes knowledge is the first step toward meaningful climate action, which is why Green Spirits has focused on educating the faithful through experiences— a river tour with the St. Johns Riverkeeper, a hike in a nature preserve with the North Florida Land Trust, a climate change documentary film series followed by Q&As with speakers, like Rosenblatt.

“My way of being an advocate is bringing information to people and hopefully igniting a fire within them to want to do something, and the energy to do something, and that seems to be happening,” Tredennick said.

Her group now has more than 120 members — many of them coming from outside of the congregation. Some members believe, if wielded properly, their knowledge of climate change and its impacts can affect policy change.

Connie Thomas, a former Mayor of Orange Park and a member of Green Spirits, said, “Sitting down with your elected official and describing how a certain environmental situation is impacting your neighborhood is huge. It says a lot. If an elected official can start putting faces and stories with a situation, it makes a huge difference.”

City Councilman Matt Carlucci, then chair of Jacksonville’s Special Committee on Resiliency, was scheduled to speak at a Green Spirits event in April, but that and all other events since have been cancelled due to the pandemic, and the outreach has been limited almost exclusively to a newsletter. Tredennick hopes to reconvene small group meetings by the spring of 2021.

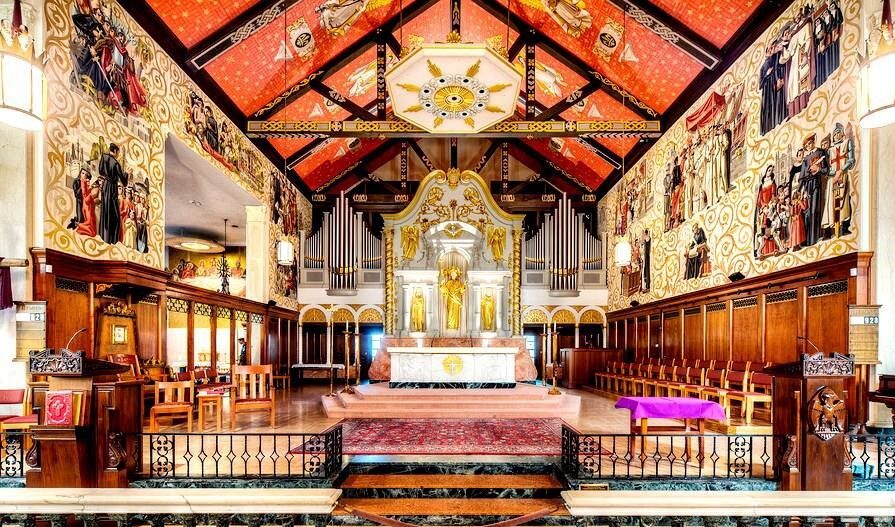

Meanwhile, another local faith organization has continued its effort to combat climate change throughout the year. The Catholic Diocese of St. Augustine, which includes 17 counties stretching from the east to the west coast of Florida, has quietly been working on an environmental stewardship action plan focused on the Jacksonville area.

“We are looking at how to address the concerns Pope Francis stated in Laudato si’ in a tangible, effective way for Northeast Florida, considering the environmental threats to people, land and our ways of life in Northeast Florida, climate change being one of the big drivers of that,” explained Lee Ann Clements, professor of biology and marine science at Jacksonville University and chair of the Diocese of St. Augustine’s steering committee on “integral ecology.”

In a 2015 writing, Pope Francis called for action. “Climate change is a global problem with grave implications: environmental, social, economic, political and for the distribution of goods,” the document reads. “There is an urgent need to develop policies so that, in the next few years, the emission of carbon dioxide and other highly polluting gases can be drastically reduced, for example, substituting for fossil fuels and developing sources of renewable energy.”

In the fall of 2019, Bishop Felipe Estévez heeded that call, commissioning the new committee to come up with ways “to be faithful stewards of God’s creation.”

Clements, who has been a member of the diocese since she moved to Jacksonville 31 years ago, was asked to lead that effort. After months of work, her committee produced “Care for Our Common Home: The Integral Ecology Plan for the Diocese of St. Augustine” this October.

The document lays out a three-pronged approach to tackling climate change and other environmental issues: education, a diocese-wide commitment to reduce consumption and waste (i.e. carbon emissions) and advocating for solutions.

While groups like Green Spirits and efforts like the one being undertaken by the Diocese of St. Augustine can be found throughout the country, an organized focus on climate change is not yet the norm among churches and faith-based organizations in the U.S.

But as more than 7-out-of-10 Americans agree that climate change is real, why aren’t more religious institutions working towards solutions? “The problem is not the people who don’t agree that it’s real. The problem is the people who don’t think that it matters, and that is most of us,” Hayhoe explained. “The majority of us don’t think it matters to us personally.”

A recent poll from Climate Nexus, in partnership with the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and the George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication, found that 65% of non-Christian Americans say they are “very worried” about climate change and a similar percentage say it is already having a moderate to large effect on their families’ health.

But that same poll found that less than a quarter of white evangelicals (the largest religious group in Florida and the nation) are “very worried” about climate change, and more than half think it’s having little to no effect on their families’ health.

While there are examples of non-Christian religions’ tackling climate change, many in minority religions don’t have the time or resources to do so, according to Matt Hartley, associate director of the Interfaith Center at the University of North Florida and board chair for the Interfaith Center of Northeast Florida.

“I think religious minority groups often find their civic resources absorbed by educating others about their religion, raising issues of bigotry and prejudice, establishing a place for their community and ensuring the safety of their places of worship, which are often targets for prejudice-motivated violence, as has been the case in our city,” he said.

And, because the effects of climate change are disproportionately impacting minorities, Hartley worries that as time passes, religious minority groups will be less and less able to focus on addressing the root causes of climate change.

“The downstream deleterious impacts of climate change could indeed contribute to keeping such groups focused on immediate concerns of safety and civic belonging; whether direct climate/weather/sea level impacts or social-safety impacts,” he said.

Within America’s white evangelical community, Hartley said, climate inaction is largely due to a strong anti-science sentiment.

“I grew up kind of on the edges of white evangelical Christianity, and there was always this kind of perceived conflict with science,” he said.

Beyond religious affiliation, though, studies have shown that rejection of climate science is mostly driven by political ideology rather than faith.

“The political polarization and the arguments over climate science and climate action, they’re really a symptom of a deeper underlying problem, which is the political polarization, fragmentation and tribalism of our society, which leads us to prioritize our identity and our ideology over facts and information and data,” Hayhoe said. “And we’re seeing this with the pandemic.”

Despite that divide, there is an ongoing generational shift among people of faith, locally and across the nation.

“Climate change and care of the earth seem to be much more palatable issues for young religious people than when I was in college 20 years ago. Even the campus ministers that I work with who are evangelical are more concerned about climate than the evangelical campus ministers that I worked with 20 years ago,” said Hartley.

This trend has led to the advent of groups like Young Evangelicals for Climate Action, a faith-based climate advocacy movement of young Christians in the U.S.

“Addressing climate change with compassion and action is deeply Christian. Scripture is full of examples of God’s abiding love for creation and our call to take care of it (all those “and God saw that it was good” references in Genesis, for instance),” Rev. Kyle Meyaard-Schaap, national organizer for Young Evangelicals for Climate Action, wrote for GRIST ahead of the November 2020 election. “For Christians, safeguarding God’s works and protecting vulnerable people from climate pollution are both invitations to get better at following Jesus — the Jesus who said that nothing was more important than loving God and loving our neighbors.”

For these faith-based efforts to be effective, Hartley believes people of all religions need to figure out how to work with those who aren’t spiritual.

“As faith communities, we need to start doing our part to prepare for what’s going to be happening in our area because of climate change,” he said. “I think we have more power when we’re all together.”