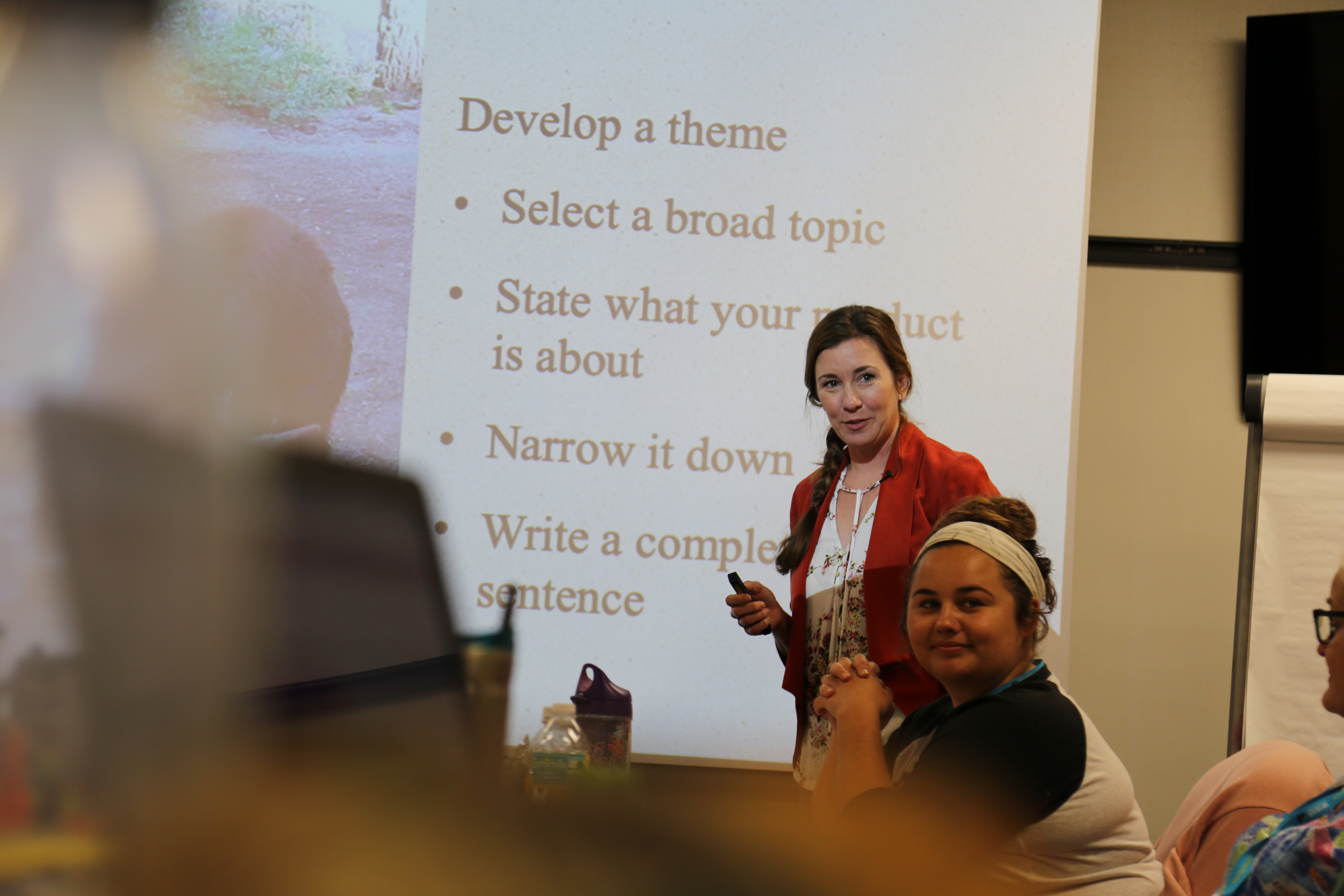

Lauren Watkins teaches people how to talk about climate change as the Director of Behavior Change Strategies for Impact By Design

You train professionals in climate change communication. Who attends the sessions?

Typically they’re for people who are working in institutions like museums and parks, where they’re trying to change audience behaviors, but the techniques we teach, called “strategic framing,” work day to day.

We want people to feel like they have the capacity to talk about issues in a way that’s not going to turn into a Thanksgiving table blowout.

How can we start a conversation about climate change?

The best way you can start is with a value you know you’re going to agree on — safety, security, loving your family. Try to maintain the tone of, we’re in it together. It’s not about your politics or mine, or your religion.

Research shows one value that resonates in America and Canada is protection. What that looks like is saying something like, “Regardless of whether it’s a partisan issue or human caused or not, we just want to protect the people and places we care about from harm.”

My own mom and I butt heads in our politics and our beliefs about climate change. It’s difficult to have those conversations, particularly when you feel like you’re up against an opposing ideology.

“Not everybody cares about polar bears in the Arctic.”

– Lauren Watkins, Director of Behavior Change Strategies, Impact By Design

Are some values ineffective when talking about climate change?

One is the cute critter trap. Seeing that polar bear hanging on to that last ice cube in the middle of the ocean is very triggering, but it’s not necessarily productive. Not everybody cares about polar bears in the Arctic. People tend to value something universal, like family.

Another one that backfires is, “Science says so.” That can come across as elitist and shut people down who feel like they don’t know a lot about science.

Let’s say we’ve established a shared value. What’s the next step?

Help people understand what’s happening. For example, use a metaphor for the role carbon dioxide plays in the environment, like, “If we burn fossil fuels for energy, we add more carbon dioxide to the atmosphere. The atmosphere is kind of like a blanket around our earth, and the more CO2 we add to that blanket, the thicker it gets, the hotter it gets. Now we’re wrapped in this heat-trapping blanket.”

What should we avoid?

Try not to use words that imply political bias. Instead of “politician,” talk about “elected officials.” Instead of “policy,” talk about “initiatives” people can get behind.

Another thing to watch out for: the “carbon dioxide is normal” argument. We hear that a lot, that carbon dioxide is a normal part of our environment, from people who lean toward denying climate change is a problem. And it is natural. But we also know excess carbon is not natural.

Why is it important to include solutions when talking about climate change?

The fastest way to make someone feel completely hopeless is to tell them how bad something is and then say, “See you later.”

Information and awareness raising rarely change someone’s actions. Give them a solution as part of that story to make them feel like there’s something they can do.

The Guardian recently changed the language it uses in climate reporting, including referring to climate change instead as “the climate crisis.” What do you think of that change?

I don’t think it’s inaccurate, but it can be problematic for the general public.

What is a crisis? My crisis might be that I don’t have enough money to pay my bills this month, working two or three jobs.

At MOSH (Jacksonville’s Museum of Science and History), people go there to be entertained and educated. They don’t want to hear a crisis tone when they’re trying to take their fourth-grader on a field trip. They want to see something hopeful.

I’m okay with “climate crisis” as long as you frame it as an opportunity for coming together and solving a problem together too.

What kind of solutions should we talk about?

They have to match the scale of the problem. Individual actions, like switching to LEDs or buying a Prius, can help address some issues. But we often see people promoting them as a way to solve climate change, and that’s problematic because they don’t match the scale — or they don’t have anything to do with climate change. Plastic straws aren’t connected to climate change. Your city’s recycling is not going to address climate change.

To solve a crisis, it takes a lot more than people changing light bulbs in their houses.

Let’s say you work on a carpool collaborative with your local school so you’re reducing fossil fuel use, or you pressure the city of Jacksonville to have a bike share program like we see in other cities like Madison, Wisconsin, to try to get some cars off the road?

Community can mean anything as long as it’s not just one thing you’re doing in a vacuum at home.

How should we handle the situation when someone pushes back with, “Climate change is happening, but it’s natural. Humans have nothing to do with it”?

We use a technique called bridging and pivoting. Trying to make them feel heard is really important.

Don’t call them an idiot. Say, “Yeah, actually, you’re right. It is part of a natural process. But we also know, mathematically speaking, if everybody starts driving a car that has a really low miles per gallon and you’re putting out a lot of CO2…[insert heat-trapping blanket metaphor here].”

In Ponte Vedra, we led a public workshop. There was someone there who vehemently denied climate change. He felt like it was a platform and he wanted to deny sea level rise. He was angry and worked up. We gave him an opportunity to say what he had to say and used his feelings as an opportunity to explore: “What could we talk about that would make you feel more comfortable as a solution, given that we know the climate is changing, regardless of why?”

It was scary. Not necessarily as scary as the conversations with my mom, but still scary.

It seems important to listen, no matter what, then?

Instead of seeing that as someone challenging your character, see it as, “This person feels comfortable enough with me to argue with me. So I’m going to take that as a compliment.”

Coming from someone who has family who deeply opposes climate science, you can get to neutral ground and think about solutions.

Any other tips or advice?

One that I learned that was emotionally very freeing is that you don’t need to be a climate science expert. You can have these conversations without having an arsenal of scientific facts to blurt out. We know that people tend to not remember scientific facts anyway.

This Q&A has been edited and condensed for clarity and brevity.