From 1970 to 1974, Jacksonville was the headquarters of the first magazine to serve Florida’s gay community. In honor of the last week of Pride Month, here’s a look at the history and impact of David magazine.

Jacksonville’s LGBTQ history dates back thousands of years. The native Mocama Timucua people had gender roles for two-spirits — individuals who belong to a third or nonbinary gender — and same-sex relationships were common. In the 20th century, despite laws and social norms that repressed and ostracized LGBTQ people, LGBTQ citizens quietly formed communities and played roles in shaping the city. In the early 20th century, Black LGBTQ musicians and performers like Ma Rainey and Bessie Smith helped establish the LaVilla neighborhood as a hotbed of blues and jazz music. By the 1950s, gay bars and clubs could be found in the city, and through the 1960s, the bohemian neighborhood of Riverside attracted LGBTQ individuals and families, emerging as Jacksonville’s first substantial “gayborhood.” Despite an often hostile social climate, the quiet but steady growth of Jacksonville’s LGBTQ community led to new opportunities for connection and visibility.

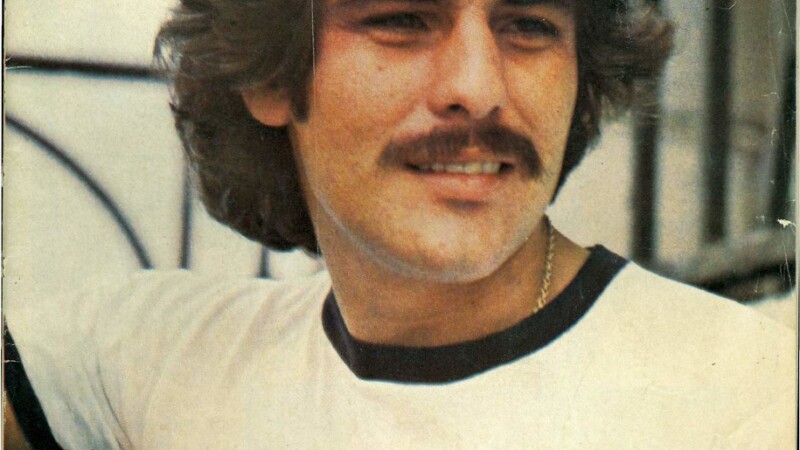

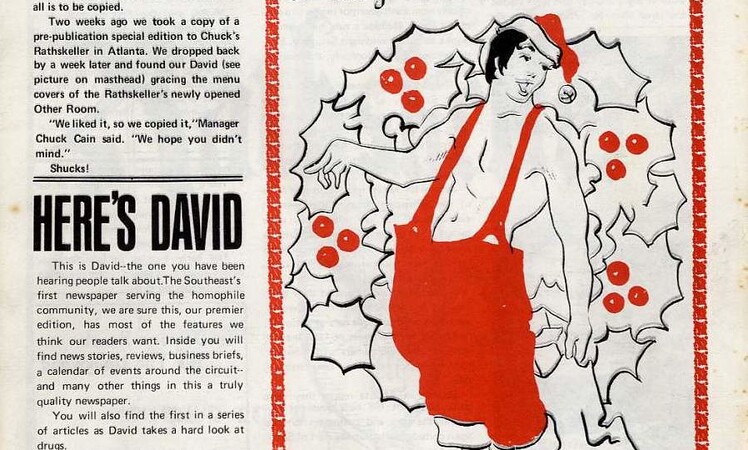

In 1970, Jacksonville got something it had never had before: a monthly magazine catering to the gay community. The pioneering magazine David was the brainchild of Henry C. Godley and Mark W. Riley, who served as editor-in-chief and managing editor, respectively (the first issue lists G.A. Murphy as the editor). Named after Michelangelo’s David, the magazine advertised its mission as “Entertaining and Informing Gays.” During its run in Jacksonville, David’s offices were listed at 9876 Atlantic Blvd., which was also the address of a gay bar called Knight Out.

David’s first commercial issue was released in December 1970, following a pre-publication special edition that year. The first issue declared, “This is David – the one you have been hearing people talking about,” noting it was “the Southeast’s first newspaper serving the homophile community.”

The editors proudly declared that unlike other gay-oriented publications, “David is not an underground newspaper.” It sold for 50 cents, a typical price for mainstream magazines at the time, and was distributed at established businesses and newsstands across Florida and Georgia. The editors stated that David would cover not only gay issues, but all stories and topics of interest to the gay community, writing, “David is not a homosexual newspaper — but a newspaper for homosexuals.”

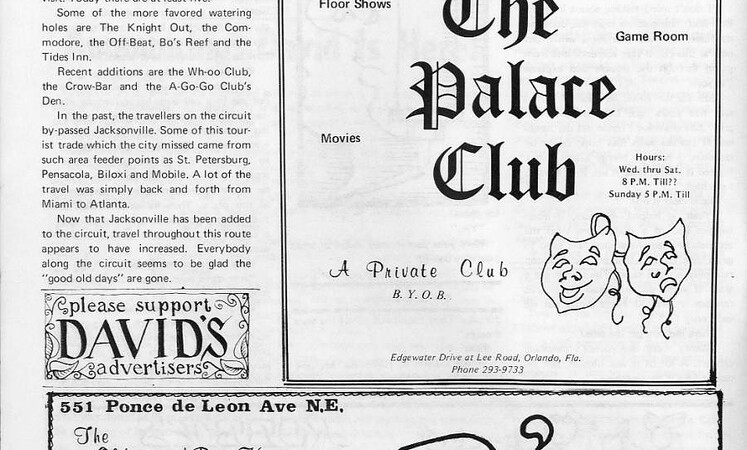

David’s first issue contained pieces on LGBTQ events, drag shows and theatrical performances, primarily in Florida and Georgia. It also included news stories, a bar guide, travel pieces and a feature on drug abuse. One article described Jacksonville’s growth as a destination on “the circuit,” the collective of bars and clubs that gay travelers in the Southeast would visit along the route between Atlanta and Miami.

“In the past, the travelers on the circuit bypassed Jacksonville,” the author wrote. “Three years ago there were only two gay bars or nightspots for the crowd to visit. Today there are at least five.”

Jacksonville venues mentioned in the piece included the Knight Out, the Commodore, the Off-Beat, the Tides Inn, Wh-oo Bottle Club, the Crow-Bar, the A-Go-Go Club’s Den and Bo’s Reef (Jacksonville’s longest running gay bar, later known as Bo’s Coral Reef).

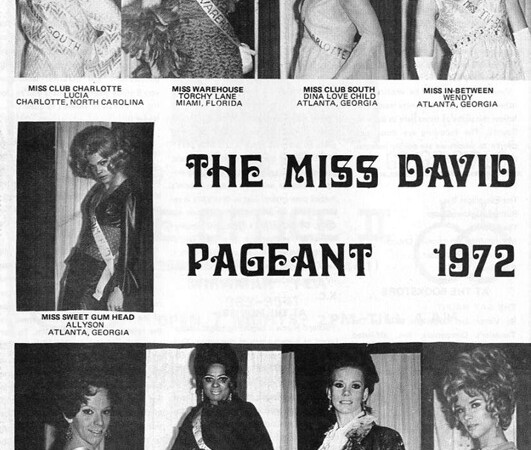

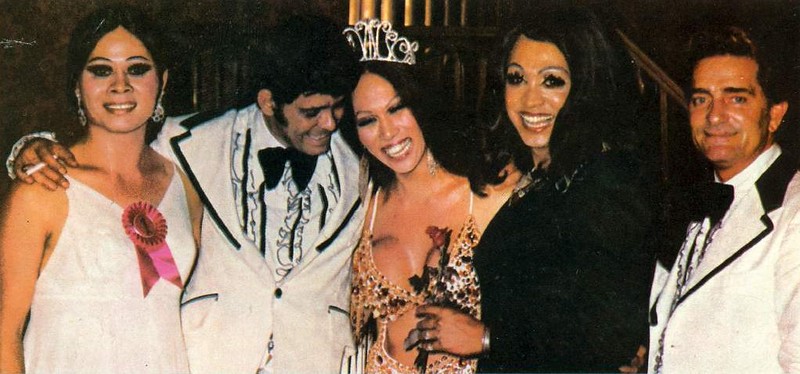

As David’s profile grew, its coverage spread to include much of the Southeast and beyond. The February 1972 issue was devoted to the gay scene of Texas. The magazine also transitioned to higher quality paper and featured photographs, particularly of nude or lightly clad models. In 1972, David launched its own drag competition, the Miss David contest. Drag queens and transgender women competed for the title during an event at Jacksonville’s Knight Out club.

Miami drag performer Torchy Lane, representing the Warehouse nightclub, won the inaugural Miss David crown. The event was so successful that the magazine launched a Mr. David contest later that year. Both events became annual affairs and evolved into the David Convention, held each year over several days in different cities. The 1975 David Convention was a five-day blowout held at Miami Beach’s Marco Polo Hotel.

David also delved into politics. The February 1973 issue discussed Florida Attorney General Robert L. Shevin’s efforts to decriminalize private sex acts between consenting adults and overturn laws that had long been used as a cudgel against LGBTQ people. “Much of the persecution of homosexuals now experienced is rooted in its illegality,” Shevin wrote. “If the above legal reform could be realized, the legal basis for discrimination would be removed and full rights of employment and housing could be realized through civil litigation in much the same way Blacks have realized their civil rights.” The September 1973 issue included a letter from Harvey Milk requesting support from the gay community nationwide for his first run for the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. Though Milk lost that race, it paved the way for his successful run for supervisor in 1977.

In 1974, Godley and Riley relocated David to Fort Lauderdale. Its success bred competitors. The launch of another gay travel publication, Michael’s of Florida Travel Guide, in 1974 drew away many of David’s advertisers. Facing declining revenues, the owners reduced the size and frequency of the main magazine while adding a second monthly travel guide called Little David. In 1975, the magazine was reformatted as a much smaller weekly publication and renamed This Week with David. Godley and Riley also pivoted the business, founding the International David Society, which offered an array of services for LGBTQ customers including travel agents and health insurance in addition to publishing.

David magazine went through a number of iterations from there, but it never regained its earlier prominence. To some extent, it appears to have been a victim of its own success. David proved there was an untapped market for high-quality gay lifestyle and travel publications in Florida and the Southeastern U.S. The International David Society was dissolved in 1990, just before Godley’s death in 1991 and Riley’s in 1993, and David magazine was no more.

However, its impact on LGBTQ life in the Southeast was significant. As Jeff Auer of OutHistory wrote, “David was the precursor to popular gay magazines of later decades.” In 1998, the original David was followed by a new publication called David Atlanta, which remained in print in one form or another until 2017. Jacksonville has been home to a series of LGBTQ magazines over the years, most recently JaxGay Magazine.

Modern scholars of LGBTQ publications have also given David well-deserved attention as the trailblazing first LGBTQ magazine in the Southeast. Websites like OutHistory and Houston LGBT History chronicle the history of the magazine and feature past issues, and physical issues have been preserved in the University of South Florida Libraries’ LGBTQ+ Collections and the University of Miami Libraries’ special collections.

Hopefully, these efforts will inspire further attention for this lost piece of Jacksonville history in the years to come.