Though less well known than those in South Florida or Tampa Bay, Jacksonville’s Hispanic community has roots that are hundreds of years deep, and it’s helped shape all aspects of life in the city throughout its history. It’s high time Jacksonville’s Hispanic heritage got its due.

Colonial period and Los Floridanos

The Jacksonville area’s connection to the Hispanic world predates the founding of the city by centuries – in fact, it dates back to the earliest days of Spanish colonization in the mainland U.S. The Spanish Empire established the colony of St. Augustine in 1565 to solidify its claims on Florida and expel the French settlement of Fort Caroline, founded two years earlier in what’s now Jacksonville. Thereafter, the Spanish settled haciendas and established missions to the Indigenous peoples around northern Florida and southern Georgia. Among the lasting contributions of this time, Spanish colonists named the Rio San Juan, or the St. Johns River.

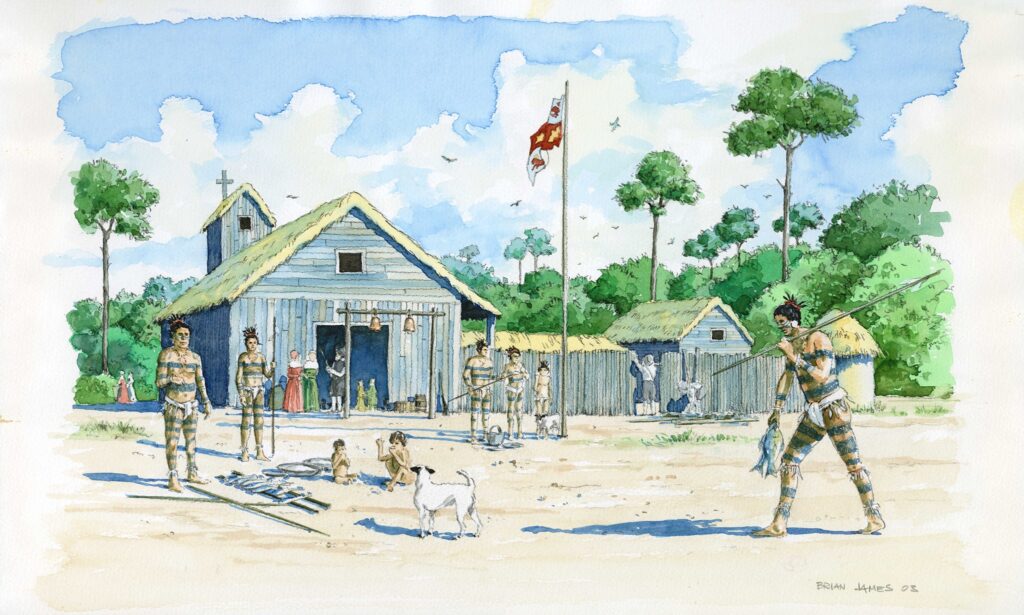

The biggest Spanish mission in what’s now Jacksonville was San Juan del Puerto, a mission to the Mocama Timucua people living on Fort George Island. Friar Franscisco Pareja served at the mission from 1595 to 1616. He devised a writing system for the Timucua language and wrote several works in the tongue which survive today, preserving invaluable information about the region’s Indigenous peoples.

Spanish Florida was governed out of Cuba, establishing long and continuing ties with the island and other parts of the Spanish Empire. Spanish subjects born in Florida were known as Floridanos, a group that still has thousands of descendants in Northeast Florida today. Spanish Florida was diverse, with a population including the Floridanos, Timucua and other Indigenous peoples, free and enslaved Africans, and others from across the Spanish Empire and various European countries. During Florida’s British period from 1763-1783, another group with Spanish connections arrived in northern Florida. Andrew Turnbull recruited hundreds of settlers from the Spanish island of Menorca and others from the islands of modern Italy, Greece and Turkey to work the failed New Smyrna colony. The Minorcans relocated to present-day St. Johns County, where their descendants number 25,000 today, and they’ve heavily influenced the culinary culture of Northeast Florida with contributions like the datil pepper and Minorcan chowder.

The Floridano population was never large, and in Florida’s second Spanish period from 1784 to 1821, the colonial government issued land grants to encourage further settlement from the empire, the United States and elsewhere. One such land grant, issued to Maria Suarez Taylor, in 1815, formed the basis of the original town of Jacksonville. After Taylor’s husband Purnal had been killed by U.S.-aligned forces during the Patriot War of 1812-14, the Spanish government awarded her 200 acres on the north bank of the St. Johns River at the Cow Ford. In 1816, Maria and her second husband Zachariah Hogans built their home on this property, and in 1822, they joined Isaiah Hart in donating land for the original platting of Jacksonville.

St. Elmo W. “Chic” Acosta

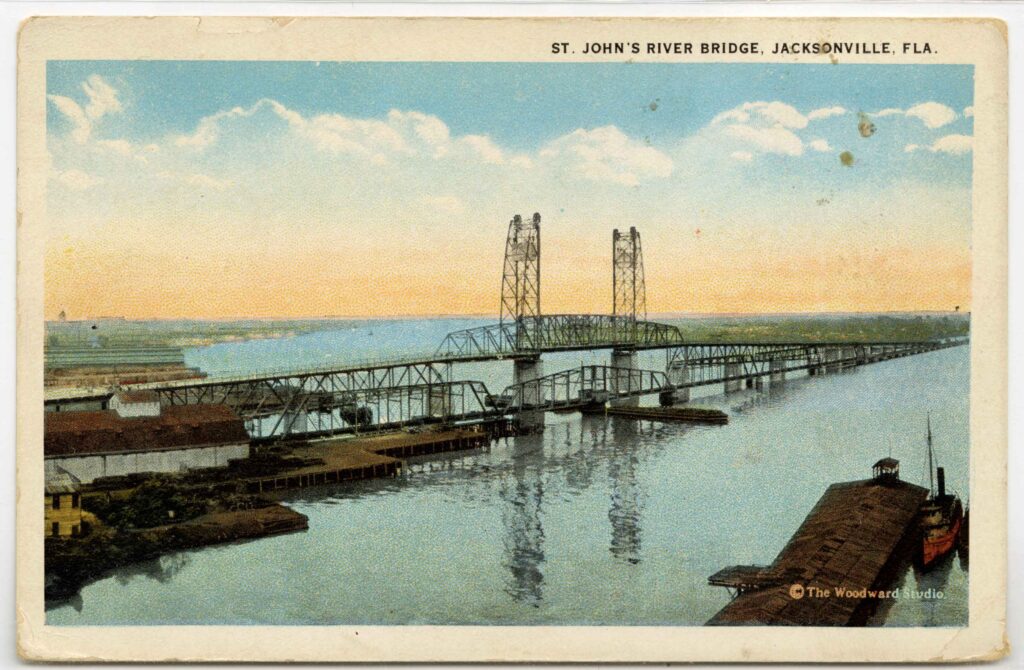

The original Floridanos integrated into the wider community, and their descendants have contributed to all aspects of life in Northeast Florida. One of the best known is St. Elmo W. Acosta, known as Chic, a Jaxson who lived from 1875 – 1947. He served as a Jacksonville City Council Member (1910 and 1914), member of the Florida Legislature (1913-1914) and City Commissioner of Parks (1919-1936). His major accomplishments included substantial expansion of the city’s park system and securing funding for the first car bridge to span the St. Johns River in Jacksonville.

The St. Johns River bridge, the first of the city’s Seven Bridges, brought massive investment and development to Jacksonville and helped secure its place as the logistics hub of Florida. In 1949, two years after Acosta’s death, bridge was named the St. Elmo W. Acosta Bridge in honor of his contributions. The bridge was replaced with the present concrete structure in 1990, still named after Acosta.

Jacksonville’s Cuban cigar industry

In the late 19th century, Jacksonville saw a new influx of immigrants from the Hispanic world, particularly Cuba. Commercial cigar rolling in Florida dates back as far as the 1830s, and the state became a major locale for Cuban cigar factories starting with Samuel Seidenberg’s “clear Cuban” cigar factory in Key West in 1867. Soon thereafter Jacksonville, a rail hub and port, emerged as an attractive hub for processing Havana tobacco.

By 1895, Jacksonville was home to 15 cigar manufacturing companies and thousands of Cuban immigrants. Most of the city’s cigar makers were clustered into two areas within walking distance of Bay Street, East Bay aroud Liberty Street, and West Bay in the vicinity of LaVilla’s Broad Street. The largest, Gabriel Hidalgo Gato’s El Modelo Cigar Manufacturing Company, employed 225 workers and produced six million stogies annually. The old El Modelo building at 501 West Bay Street was one of the few Downtown buildings to survive the Great Fire of 1901, and still stands today at the foot of the Main Street Bridge.

Hidalgo Gato’s brother-in-law José Alejandro Huau, was also a cigar factory owner and a popular Jacksonville personality. Initially operating his factory with another brother-in-law, he became sole owner in 1876 and changed the name to Huau & Co., later appending his wife Catalina Catalina’s initials to make it C.M. de Huau & Co. The business, which made El Esmero cigars, grew to employ 150 workers in a large building on Bay Street and a cigar store at Bay and Pine (Main) Streets that was said to be the finest in the city. Huau parlayed the success of his business into a political career, serving three two-year terms in the Jacksonville City Council. Though a proud U.S. citizen, he kept abreast of the struggles of his homeland and worked for years towards independence from Spain. With the assistance of Huau, José Martí visited Jacksonville eight times between 1891 and 1898, stirring up enthusiasm and financial support for Cuba’s freedom movement.

The Lolita Cigar Company was another Cuban cigar factory that operated in the ground floor of the former Central Hotel on Broad Street in LaVilla. Its owners were Julio C. Pulgaron and Carlos Ortega. Pulgaron also operated cigar making businesses on Davis, Johnson and West Ashley Streets. Another cigar manufacturer that left a surviving building was the Sola & Gonzalez Company, which briefly operated a factory at 322 Broad Street in 1911. Its owners were Jose de Sola, originally from Havana, and Mario Gonzalez, who lived in Tampa.

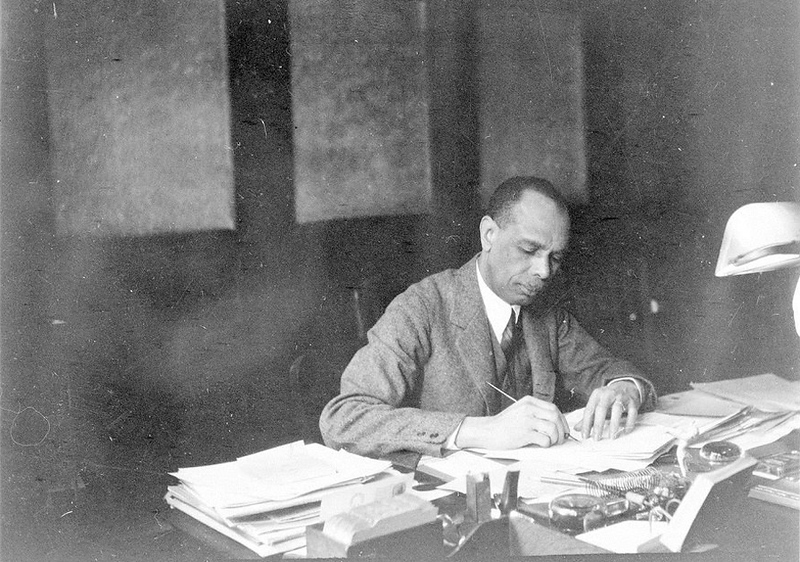

Jacksonville’s greatest native son, James Weldon Johnson, grew up in LaVilla at the height of the Cuban cigar industry and was well ingrained with the Spanish-speaking community, and Johnson learned Spanish as a boy. As a teenager, the Johnson family took in a young mixed-race Cuban named Ricardo Rodriguez (later Ricardo Rodriguez Ponce), evidently the son of a Cuban aristocrat. Johnson and Rodriguez Ponce remained lifelong friends; in his autobiography, Johnson credits Ricardo with improving his Spanish and teaching him to smoke. Johnson put his mastery of Spanish to good use as an adult when he served as U.S. Consul to Venezuela from 1906 to 1908 and Nicaragua from 1909 to 1913. Jacksonville’s Cuban community plays a significant part in Johnson’s autobiography Along This Way and his novel The Autobiography of an Ex-Colored Man.

Jacksonville’s hand rolled cigar industry eventually declined with the emergence of Tampa’s Ybor City and later, mechanical cigar manufacture such as that pioneered by fellow Jacksonville cigar company Swisher, one of the few remaining representatives of an industry that once dominated Florida’s economy.

Cuban Independence and Camp Cuba Libre

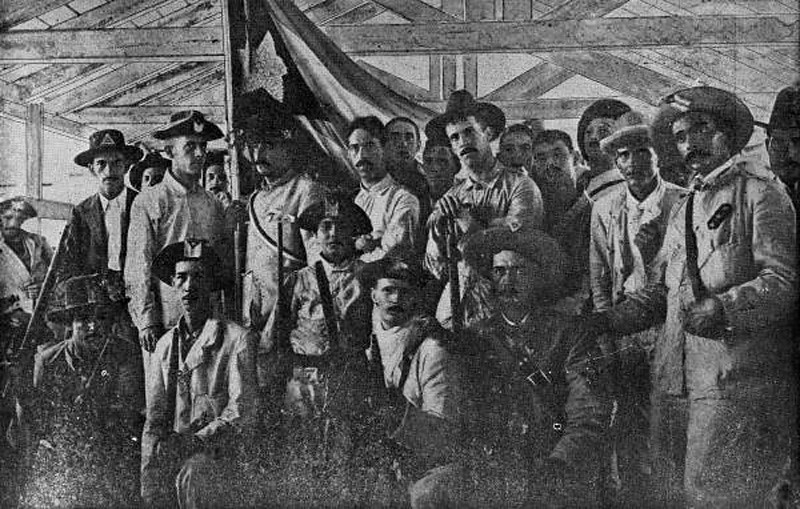

Jacksonville’s Cuban community played a role in their homeland’s quest for independence. Cuban businessmen like Gabriel Hidalgo Gato and Jose Alejandro Huau hosted Jose Marti and other leaders, and helped rally support for the cause among both Cubans and the wider public, and numerous Jaxsons took part in the efforts.

In May 1898 with the outset of the Spanish-American War, the U.S. military formed Camp Cuba Libre in what’s now Springfield as a rallying point for troops headed to Cuba. Gathered units included the Army of the Cuban Republic, consisting of 40 Cubans from Jacksonville, 200 from New York and 150 from Key West.

Boricua Jax: Jacksonville and Puerto Rico

Jacksonville has a longstanding trade partnership with Puerto Rico and its capital of San Juan. 90% of trade between Puerto Rico and the mainland US goes through Jacksonville. Jacksonville is also the home of Puerto Rican rum distiller Bacardi’s largest factory in the Americas region. In 2009, San Juan and Jacksonville were declared sister cities.

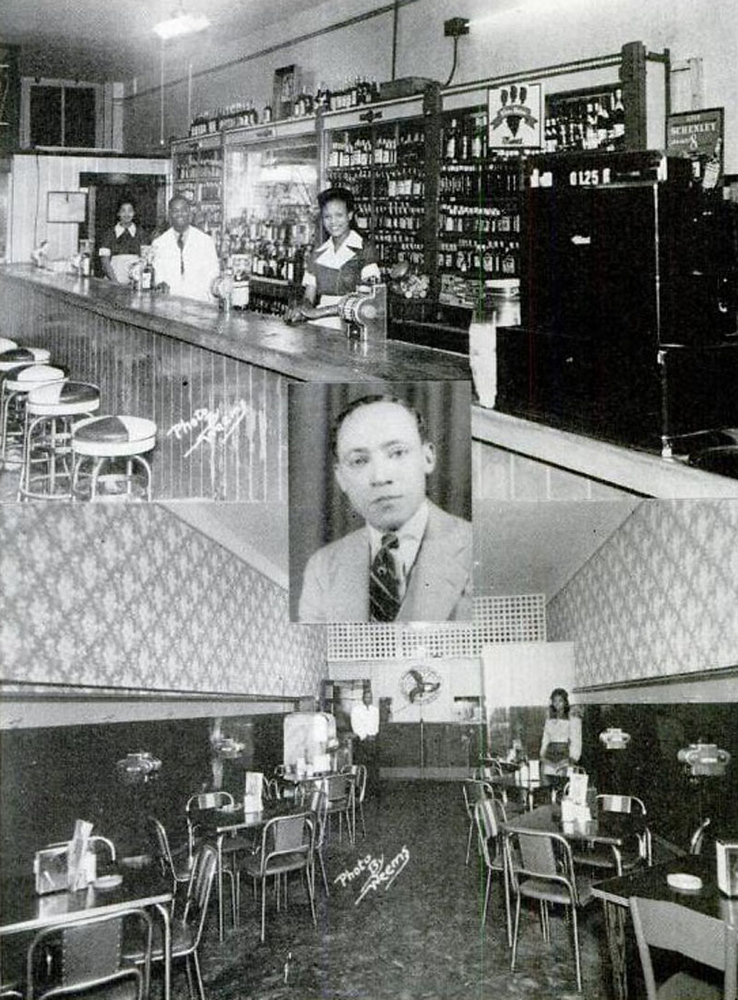

Naturally, Puerto Ricans have long played an important part in Jacksonville’s history and culture. From the early 20th century, Afro-Puerto Ricans contributed to the vibrant music, blues and civil rights scene of the city. Manuel Rivera, a pillar of Black Jacksonville society born in Puerto Rico, operated Manuel’s Tap Room on Ashley Street during the 1940s and 50s. Manuel’s was a 24-hour lounge and restaurant described by the NAACP as the “finest of its kind in the South” and hosted many up-and-coming jazz musicians including Ray Charles.

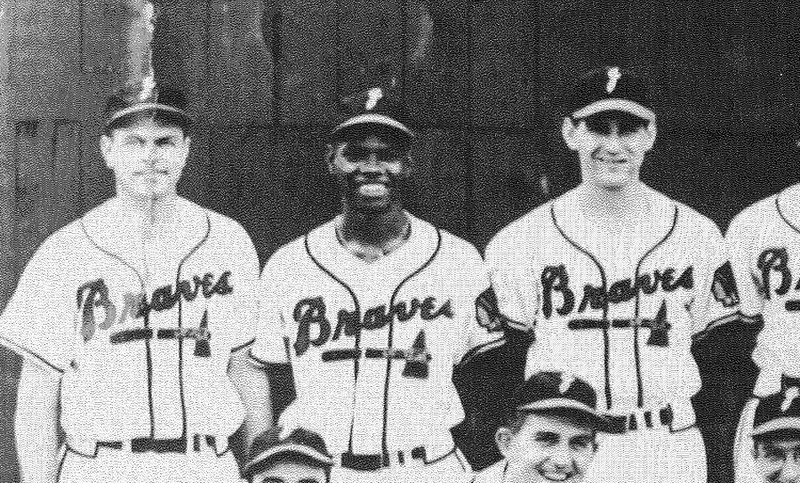

In 1953, Rivera also played a role in overcoming Jim Crow and the baseball color line by opening his home to three young Black baseball players for the Jacksonville Braves, the first integrated team in city history, and one of the first anywhere in the South. The players were future superstar Hank Aaron, career minor leaguer Horace Garner, and energetic utility man Felix Mantilla.

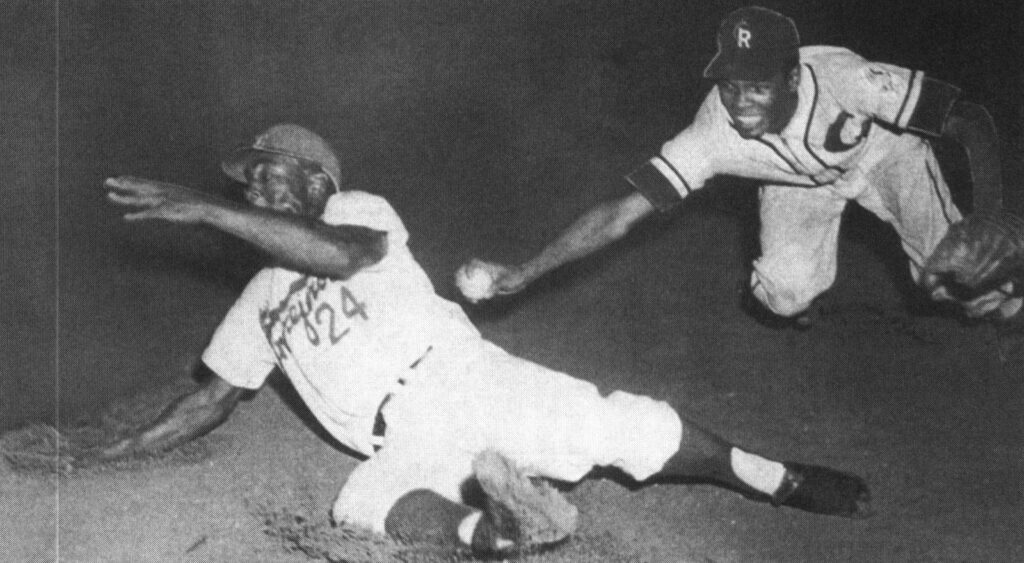

Felix Mantilla, an Afro-Puerto Rican like Manuel Rivera, had made such waves in the island’s baseball scene that the Milwaukee Braves recruited him into their farm system. Meanwhile, the Braves’ affiliate in Jacksonville were jumping at the chance to be the first team in the South Atlantic League to integrate – and to reap the rewards on the field and in the ticket box. Mantilla initially struggled to adapt to the language barrier and the brutal racial politics of the South, but with the help of Aaron, Garner and team leadership, he excelled on the field and helped make Jacksonville the league’s regular season champs. The team was also a smash success financially, and both Mantilla and Aaron were called up to higher leagues at the end of the season. Mantilla went on to an 11-year career in the majors as a distinguished utility player.

A growing community

Today, Jacksonville’s Hispanic community is more diverse than ever – and quickly growing. While Hispanics comprised only 2.6% of Duval County’s total population in 1990, this figure has grown to 13.5% – 142,951 people – as of 2024. As a result, the cultural makeup, development pattern, and flavor of long-established neighborhoods across the city continue to evolve. Tens of thousands of people of Latin and Caribbean descent, including from Mexico, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, and Venezuela, are making Jacksonville their home and reshaping their neighborhoods. Vibrant communities can be found in historic neighborhoods like Phoenix in the Eastside, established suburbs like the 103rd Street corridor and Spring Park, and newer bedroom communities like Nocatee.

To accommodate Jacksonville’s booming Hispanic communities, local leadership is reaching out like never before. Mayor Donna Deegan hired Yanira “Yaya” Cardona as the city’s first ever Hispanic outreach coordinator in 2024 and launched monthly business forums and an annual expo with the First Coast Hispanic Chamber of Commerce.

It’s a good thing, too. Jacksonville wouldn’t be what it is today without its long Hispanic legacy, and it’s high time it got its due.