The concept of urban renewal as a method for social reform emerged in England during the 19th century as a reaction to address unsanitary conditions of the urban poor. In many U.S. cities, it was used by local, state and federal governments to erase many marginalized communities from existence. Here are five examples of neighborhoods in Jacksonville that were completely erased by urban renewal.

1. Campbell Hill

More than 230,000 cars drive over the lost neighborhood of Campbell Hill everyday not knowing the history that lies under Interstate 95’s Myrtle Avenue overpass. Much smaller than its larger neighbors LaVilla and Brooklyn, Campbell Hill was a compact urban neighborhood nestled between railyards on the north side of McCoys Creek, just west of the former Jacksonville Terminal passenger railroad station. Named after Alex B. Campbell, Campbell Hill dates back to as early as 1860 with the establishment of the Florida, Atlantic and Gulf Central Railroad. Five years later, Campbell arrived in the U.S. as an immigrant from Canada, England. A Reconstruction-era capitalist, A.B. Campbell’s investments included owning and operating Merryday & Paine’s Music Store, along with a fine printing business and real estate.

During the early 1880s, Campbell purchased, surveyed and platted Campbell Hill, the Eastside’s Campbell’s Addition, in addition to being the Secretary of the Jacksonville Cemetery Association and selling land for the development of Evergreen Cemetery. Campbell also published the first works of famed composer Frederick Theodore Albert Delius in 1885. After the opening of Henry Flagler’s Jacksonville Terminal, Campbell Hill became a desired location for the men and women who provided the physical labor.

One of Campbell Hill’s most famous residents was Frank Benjamin “Frankie” Manning. During the Great Migration, Manning’s mother, who was a dancer, left Jacksonville, moving the family to New York in 1917. Learning to dance at an early age, Manning eventually became known as one of the founding fathers of the Lindy Hop and Swing Dancing. During his career he toured with Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, and others. He also appeared in movies including Jittering Jitterbugs and Hot Chocolate, Malcolm X and Stomping at the Savoy.

Campbell Hill remained relatively untouched and vibrant until the construction of Interstate 95’s Myrtle Avenue overpass in 1957. Subsequent expansions to Interstate 95 have resulted in the elimination of most of the neighborhood. Today, only four isolated buildings remain in the neighborhood.

2. East Jacksonville

The neighborhood of East Jacksonville originated along the St. Johns River, just east of Hogans Creek, after the end of the Civil War. Prior to the Civil War, East Jacksonville’s waterfront was lined with lumber mills and wharves that utilized industrial enslaved labor. A part of a 225-acre Spanish land grant given to Daniel Hogans, East Jacksonville was generally bounded by Hogans Creek, Albert Street on the north, Haines Street on the east and the St. Johns River on the south.

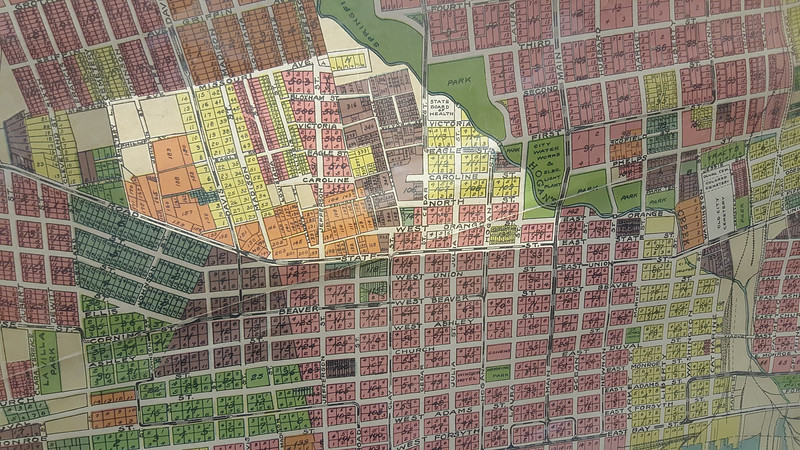

Original neighborhood street names included the likes of Brough, Julia, Leach, Victoria, Maggie, Mattie, King, St. John and Forsyth. An attempt to incorporate East Jacksonville as a municipality was defeated in 1878. Following the extension of Henry B. Plant’s streetcar line to the community and the opening of St. Luke’s Hospital, East Jacksonville began to rapidly grow. By the time it was annexed into Jacksonville in 1887, it had become a large neighborhood anchored by an industrial riverfront, cigar factories and a small commercial district straddling Florida Avenue (now A. Philip Randolph Boulevard).

Since the 1920s, East Jacksonville has largely disappeared from the map as the community has been erased by expressway construction, industrial development and the creation of the Sports and Entertainment District during the mid-20th century. Also considered a part of the Historic Eastside, the land area once known as East Jacksonville is the central focal point of plans to develop a new stadium for the Jacksonville Jaguars and supporting mixed-use development.

3. Hansontown

A Gullah Geechee community, Hansontown was founded in 1866 by Daniel Dustin Hanson, a surgeon with the 34th Regiment, U.S. Colored Infantry. Hanson intended Hansontown to become a communal farming community for Black Civil War veterans, freedmen and women to grow and sell crops. Due to his death in 1868, his vision never materialized.

However, the community along the banks of Hogans Creek did rapidly grow during Reconstruction and the late 19th century. By the time it was annexed into Jacksonville in 1887, the neighborhood’s population had increased to 1,623. Two of Hansontown’s most well-known and respected residents were Clara English White and her adopted daughter, Eartha Mary Magdalene White. During the 1880s, former slave Clara White became known for feeding hungry neighbors from her two-room house in Hansontown. In subsequent years, Dr. Eartha M.M. White molded these humanitarian acts into the thriving Clara White Mission.

Characterized by shotgun houses and 15-foot-wide unpaved streets, the working-class neighborhood became an early target for urban renewal. Considered the slums, in 1942 a large swath of the neighborhood’s west side was razed and replaced with a large public housing complex called Blodgett Homes.

As a part of a 1969 Federal urban renewal program, the Jacksonville Housing and Urban Development Department envisioned replacing the rest of the neighborhood with townhouses, garden apartments, high-rise senior housing and wide streets. This plan failed to materialize and much of the land eventually became the Downtown campus of Florida State College of Jacksonville in 1977. By this time, Blodgett Homes had become one of the city’s most dangerous places to live, leading to a large portion of that site being razed and replaced by a state office complex during the 1990s.

Today, most Jaxsons speeding down State and Union streets will find it hard to believe that there was once a dense, walkable community located between Downtown and Springfield.

4. Railroad Row

Between 1890 and 1920, more than 20 million immigrants arrived in the U.S. Many found Jacksonville’s LaVilla neighborhood as a destination to pursue the American dream. Sandwiched between three major railroad depots and the riverfront, LaVilla’s Railroad Row emerged as a place where early settlers arrived from Southern Greece and Turkey as sailors from ships that docked along the riverfront.

The oldest developed section of LaVilla, Railroad Row was a compact mixed-use district straddling West Bay and Forsyth streets between the Jacksonville Terminal and Downtown. During its heyday, the Jacksonville Terminal was the largest passenger railroad station in the South and served as an official gateway to worldwide travelers entering the city, handling as many as 20,000 passengers and 200 trains each day.

By 1910, Railroad Row had become home to many Greek-owned restaurants, fruit markets, hotels and bodegas serving the large transient population in the area. Railroad Row’s vibrancy peaked along with passenger rail travel during World War II. Following World War II, suburban growth, urban renewal and the closure of its three railroad depots brought a decline to the neighborhood. Every building along West Bay Street that remained, was razed as a part of the 1990s River City Renaissance Plan.

While much of Railroad Row no longer exists, the former Jacksonville Terminal and a small collection of historic warehouses along West Forsyth Street survive. With recent infill multifamily residential development, the Jacksonville Regional Transportation Center, the Emerald Trail and the opening of Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing Park, LaVilla’s Railroad Row has become one of Downtown’s most popular locations for infill development.

5. Sugar Hill

Sugar Hill was a middle class African American neighborhood located along West 8th Street, just west of Hogans Creek and Historic Springfield. Sugar Hill’s period of growth came with the arrival of the North Jacksonville Street Railway, Town and Improvement Co. following the Great Fire of 1901. Owned and operated by several prominent members of the Black community, the streetcar service connected LaVilla with Moncrief Park.

Anchored by the Cookman Institute (now Bethune-Cookman University in Daytona Beach), Duval County Hospital, St. Luke’s Hospital and Brewster Hospital, Sugar hill quickly became a desired residential location, leading to subdivision names such as Hendersonville, Springfield Heights, West Greeleyville, Highland Heights and College Heights. By the end of the 1920s Florida Land Boom, Sugar Hill had become characterized with numerous mansions and elegant residences of Jacksonville’s Black businessmen, attorneys, architects, doctors, educators and other professionals.

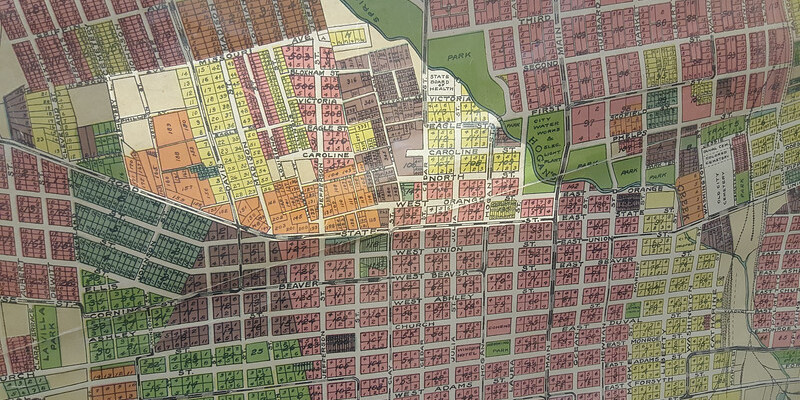

Redlined in the 1930s because of its racial demographic makeup, Sugar Hill was targeted for urban renewal through the use of local, state and federal funds in the mid-20th century. During the 1960s and 1970s, the neighborhood was largely razed for the creation of Interstate 95 and the present day UF Health Jacksonville medical complex.