The Jaguars’ roots in Jacksonville have been three decades in the making.

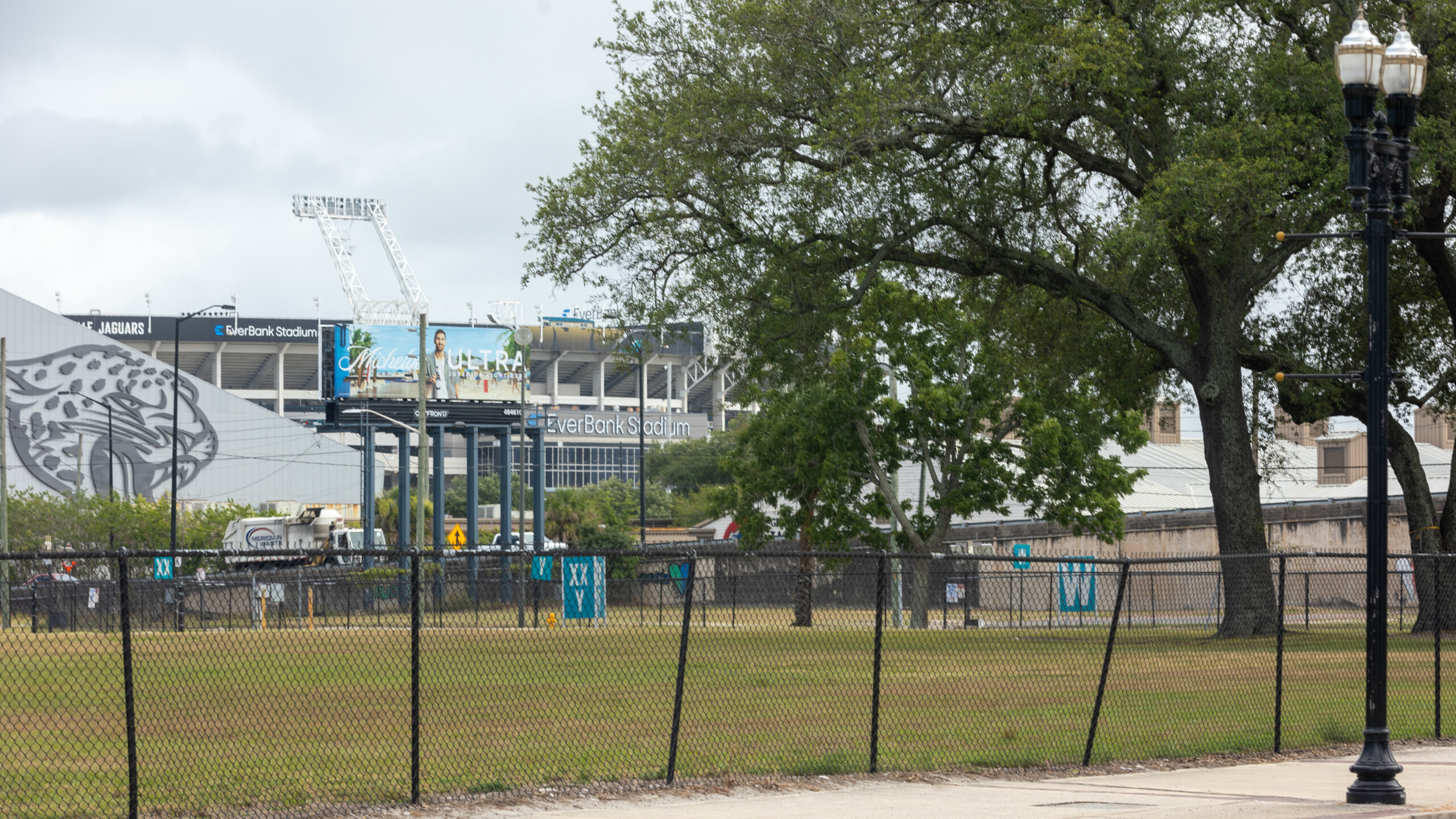

The franchise believes the City Council’s approval Tuesday of renovations to EverBank Stadium will serve as financial fertilizer for the community in the shadows of the stadium lights.

Pardon Eastside residents for being skeptical.

Residents and community leaders trust the motives of the Jaguars, who plan to devote millions to programs and community organizations on the Eastside. They trust the motives of Jacksonville Mayor Donna Deegan. But many residents tell Jacksonville Today they do not trust the Jacksonville City Council to allocate funding for the Eastside.

Initially, the Jaguars pledged to provide $150 million over 30 years while the city of Jacksonville promised another $150 million up front, creating a $300 million Community Benefits Agreement as part of the stadium deal. But the city then delayed discussion of more than $90 million of its funding, including the portion devoted to the Eastside.

The move reminded people like Bruce Moye of additional broken promises from City Hall.

Moye is president of the Eastside Brotherhood, a nonprofit that has supported the Eastside through charity and volunteerism since 1981. Moye has lived Out East for decades and implicitly trusts that the Jaguars will do what they promise.

“It’s the city. … They are thinking we don’t know any better,” Moye says. “Once they separate it, we still might get some of the funds, but it won’t be as much.”

Moye has lived Out East since 1966. He remembers the National Guard rolling along what is now called A. Philip Randolph Boulevard during a race riot in 1969. He also recalls being inside the stadium when initial Jaguars owner Wayne Weaver got off a helicopter to celebrate the NFL’s coming to Jacksonville in December 1993.

“Upgrade us on your promises so we can compete with mainstream Jacksonville,” Moye says of the city’s investment on the Eastside. “You’ve done developed Main Street. They have had two or three chances. We’re just asking for one chance. We’ve started with the Melanin Market and Black history programs. We have created things to do the whole year.”

Moye believes the Jaguars’ investment in the Eastside will spur community and business growth among members of the community, not solely outsiders and opportunists.

Jaguars owner Shad Khan says American football has the power to move communities. To this day, his claims his biggest achievement in football was helping Jacksonville pass the Human Rights Ordinance in 2017.

“This community involvement, I think everyone should benefit,” Khan told reporters Wednesday. I mean, we’re sitting in an area that, frankly, I’ve seen deteriorate over the 12 years I’ve been here. The glacial pace of how some of these things have really not been addressed, this is a great chance with us, with the mayor, with the City Council to make a difference.

“The workforce development, I think there are people here who need good jobs, construction, some of those life-altering skills, rather than importing. Growing our own is a logical one. Winning football is maybe a mission for a football team. I think making lives better is really the ultimate goal of any cultural activity like football.”

The Rev. Christopher McKee says the Community Benefits Agreement is an opportunity for the Eastside to continue the withintrification process, a revitalization effort driven by people who already live in the neighborhood as opposed to gentrification from the outside.

McKee has served as the lead pastor at The Church of Oakland in the heart of the Eastside since 2017. He knows the Jaguars are good community stewards because the church and the team have held a back-to-school drive together for years.

“It would mean the community getting what it deserves,” McKee says. “This is not by any means a handout. It is necessary reinvestment in a community that has experienced long-term disinvestment. If we want to have a conversation about how neighborhoods, especially in urban cores across this country, have dealt with disinvestment, the Out East neighborhood is an example of that. Any investment is reinvestment. It is a necessary fix to a longstanding problem.”

Around the NFL

This week might have indicated how radically different the Jaguars approach is compared to their NFL peers.

When the Buffalo Bills’ plan to build a new stadium was finalized last year, the team provided $550 million to the cost of the then-projected $1.4 billion stadium as well as $90 million in a Community Benefits Agreement. In their Community Benefits Plan, the Bills would focus on eliminating poverty, improving health and wellness as well as additional job opportunities. However, it would not focus on a specific community or prevent displacement of people in Orchard Park, New York, where the stadium is situated.

Earlier this week, the Charlotte City Council approved a package in which taxpayers would spend $650 million to renovate Bank of America Stadium.

The Jaguars and Carolina Panthers are celebrating their 30th anniversary this season. Jacksonville and Charlotte have taken different approaches to the renovation of stadiums in once-thriving Black communities.

Panthers owner David Tepper is wealthier than Jaguars owner Shad Khan; however, the Panthers are contributing less in renovations to Bank of America Stadium in downtown Charlotte than the Jaguars are for EverBank Stadium renovations.

The Panthers’ Community Benefits Plan with the city of Charlotte calls for minority small-business owners and women-owned small businesses as well as programs “for veterans and military families, disadvantaged and at-risk youth, and low-income residents.”

Meanwhile, Jacksonville’s Community Benefits Plan is the largest in NFL history. Currently, the team will commit $3.9 million annually over 30 years to benefit parks, countywide initiatives and the Eastside — the neighborhood that was altered in the 1920s to initially build a football site at the present location of EverBank Stadium.

Tuesday night, the City Council approved a package that would provide major renovations at the site for the third time.

Council member Jimmy Peluso, whose district includes Downtown and the Eastside, asked out loud last week whether the City Council’s deferral would accelerate the gentrification and displacement that took place in Brooklyn, Sugar Hill and LaVilla – all predominantly Black neighborhoods that were gentrified in the name of development and progress.

“Is Out East next?” Peluso asked. “I hope not.”

Some on council considered it financially prudent to defer discussion of the remaining dollars in the Community Benefits Agreement. But along A. Philip Randolph Boulevard, that move was perceived as another dream deferred.

Honey Holzendorf says she felt disrespected that some City Council members appeared inattentive during a public hearing June 17 about the stadium.

Holzendorf, who has lived Out East for six decades, doesn’t believe her community will see the Community Benefits Agreement dollars the city pledged as part of the stadium deal.

Holzendorf says she would like to see the city allocate the public dollars designated for the Eastside to the Jessie Ball duPont Fund because that nonprofit is willing to be present in the community.

“They are doing the work,” Holzendorf says of the duPont Fund. “We don’t have to worry if they will give us the money. All we have to do is ask. Jacksonville doesn’t care about the Eastside. Look at our roads.”

An hour before Holzendorf expressed that hope to Jacksonville Today, Jessie Ball duPont Fund President Mari Kuraishi attended a meeting on the Eastside — alongside community members as well as leaders from LIFT Jax and the Community Foundation for Northeast Florida — about how the neighborhood would leverage its designation as a member of the National Register of Historic Places.

Creating generational wealth

Elaine Jackson’s ties Out East run even deeper than Holzendorf’s. She is a fourth-generation resident who lives in Fort Caroline now but is frequently back in her old neighborhood volunteering with the Historic Eastside Community Development Corp.

Jackson says it’s vital that Eastside residents and community members use the influx of dollars from the Community Benefits Agreement to create generational wealth, before property values increase. One way to do so is to own the properties they live in.

A majority of the Eastside is a part of Census Tract 174, a Qualified Opportunity Zone — a federal program that uses tax benefits on capital gains taxes to spur economic development in economically distressed communities.

The U.S. Census Bureau data indicates that nearly a third of Eastside residents live in poverty (32.3%) and only 37.2% of residents own their homes. Both are worse than countywide averages (13.8% poverty and 58% homeownership).

Jackson says many of the people who inherited homes Out East chose to leave the neighborhood. That contributed to the lost connections that organizations like the Historic Eastside Community Development Corp. look to revive.

“Everyone knew each other and knew when someone was down on their luck,” Jackson tells Jacksonville Today as she sits along a bench near the recently demolished Marion Graham Mortuary. “When they hurt, we hurt. When we were hungry, they fed us. It was a community, a neighborhood. It’s not what it is today.”

Ariane Randolph is among the many looking to change that. She is an author, activist and Eastside resident who has studied Community Benefits Agreements in other communities.

Randolph argues that Eastside residents must begin to think like developers, or become the developer themselves — and that means not relying on the city’s Community Benefits dollars to revive the Eastside.

“The Community Benefits movement is about 20 years old,” Randolph says. “Oftentimes, there is an indigenous or cultural community that is driving that process, rarely a municipality that’s driving the process.”

Randolph says the more collaborative and transparent the City Council can be with Eastside residents as it discusses and allocates the remaining Community Benefits Agreement dollars, the better the process will be.

Moments after the Jaguars and Mayor Deegan outlined their plans for the stadium renovation last month, team President Mark Lamping told reporters the Community Benefits Agreement was a critical part of the team’s commitment to Jacksonville and the neighborhood where many fans park to watch Jaguars football.

“That neighborhood, which is right next to the stadium, has been underserved for generations,” Lamping told reporters in May.

“Quite honestly, we think that we need to be a catalyst to do what we can with others to solve that. So, if we are going to make a big commitment to the community, we certainly wanted our neighbors to the north to receive a disproportionate amount of that.”

Moye agrees with Lamping. He believes the city should do the same.

“That’s the whole idea of trying to keep our historical Eastside,” Moye says. “The way we grew up, we know it’s regal.”