The U.S. government created ghettoes.

Government action produced racially segregated communities in the U.S., including in Jacksonville. This was no accident. It was a policy enforced by rules and a complicit justice system.

The effects are still being felt. Therefore, those of us who have benefited — mostly innocently — need to help remedy this injustice.

Richard Rothstein broke through a national case of collective amnesia about America’s segregated housing history with his 2017 book “The Color of Law.” The book devastates the idea that segregation in much of America, especially in the North, was created by custom, individual decisions, or “de facto segregation.”

In fact, a series of government policies helped to create mostly white suburbs and mostly Black slums, Rothstein wrote. In fact, segregation even in the North was more like the “de jure segregation” created by law in the South.

The U.S. Supreme Court played a devastating role by annihilating the 14th and 15th amendments to the Constitution, Rothstein told me in a phone interview. If the civil rights guaranteed in those amendments had remained fully intact, America today would have a “racially egalitarian society,” he said.

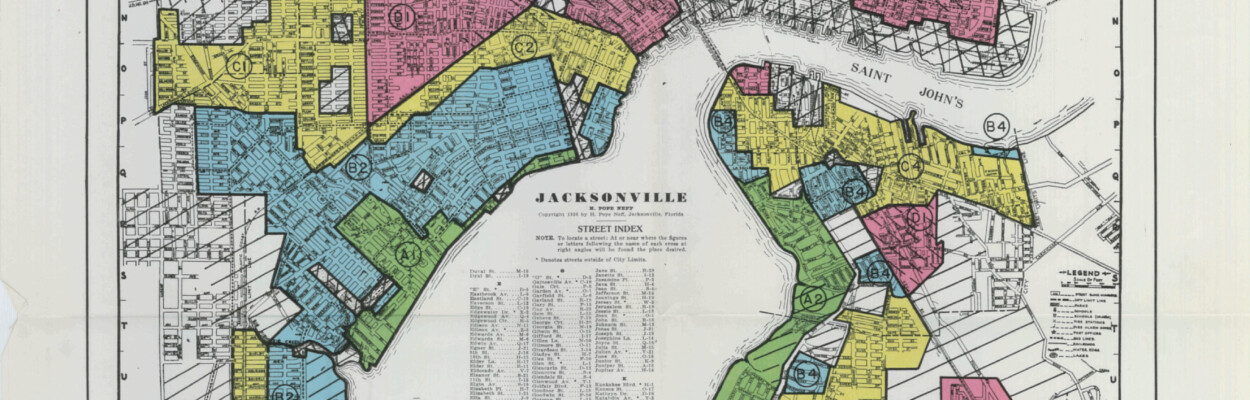

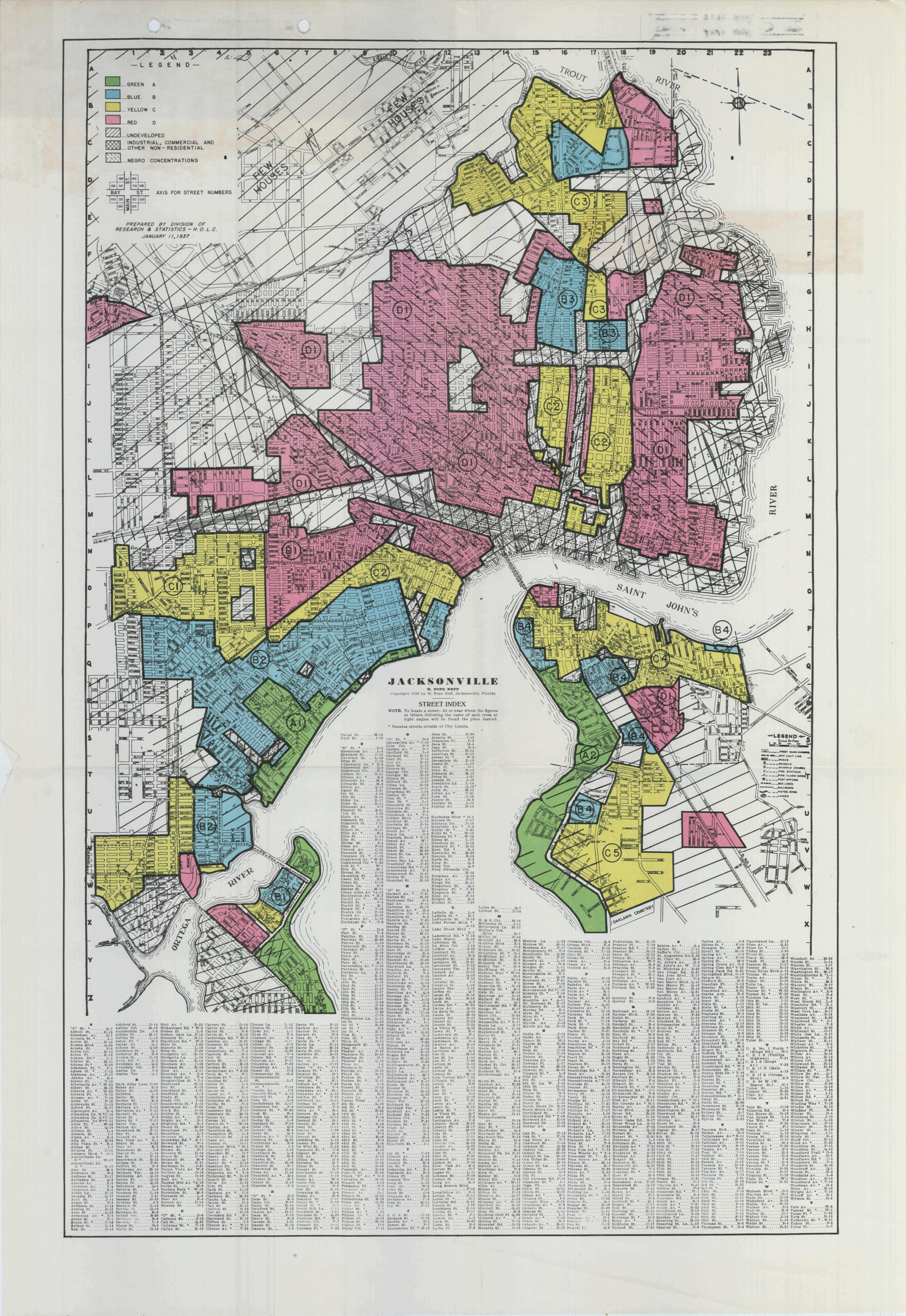

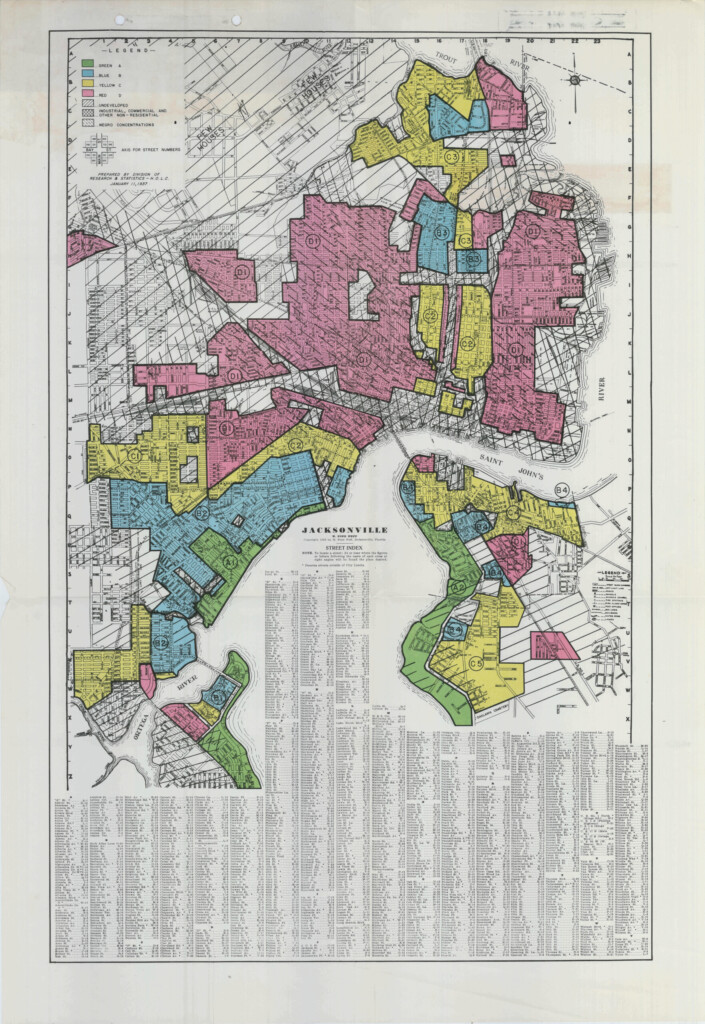

“Redlining” in the 1930s also had a devastating impact. The federal government ranked neighborhoods for home loans according to racial categories. There were four colors used for rankings. A redlined neighborhood meant mortgages were reserved for African Americans. A greenlined neighborhood was reserved for whites. Blue and yellow neighborhoods were intermediate.

In Jacksonville, the redlined neighborhoods of the 1930s are clearly identifiable today as the predominantly Black neighborhoods in Northwest Jacksonville and Pine Forest on the Southside. It’s shocking to see the sheer size of the redlined areas in the old core city and the small areas of greenlined neighborhoods along the St. Johns River in San Marco and Riverside.

But that isn’t all, Rothstein points out. The real estate industry worked to keep the nation’s housing racially segregated. A code of ethics in 1924 by the National Real Estate Association called for segregation. Also, real estate agents sought to create white flight by using blockbusting tactics.

In addition, deed restrictions prohibited Black families from moving into white neighborhoods. And the court system largely facilitated all of this.

Here is a passage from a 1950 deed restriction in Daly City, Calif.: “The real property … shall never be occupied, used or resided on by any person not of the white or Caucasion race, except in the capacity of a servant …”

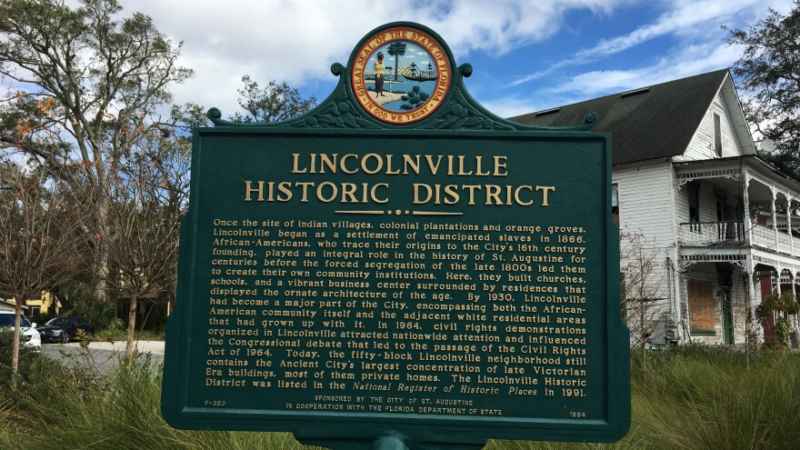

After World War II, mortgages by the FHA and VA were refused to Blacks in white neighborhoods and vice versa. Then came the interstate highway system, which broke up the African American neighborhoods in cities like Jacksonville. Meanwhile, toxic waste, trash incinerators and polluting industries tended to be in Black communities.

Bottom line, as Rothstein wrote in “The Color of Law,” segregation across America was entrenched during the 20th century by government action. It was so effective that Rothstein calls it “residential apartheid.”

So what should have happened?

The government should have declined to segregate neighborhoods by race. The government could have declined to insure FHA and VA mortgages for racially exclusive neighborhoods. The government should have taken action against racial discrimination in housing policies like deed restrictions. The examples go on.

Finally, in 1968, after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the government passed the Fair Housing Act. But the damage had been done.

Once entrenched, segregation is difficult to reverse, so the easiest course is to ignore it. The injustices become entrenched. To follow discrimination with race-neutral policies will leave behind future generations of African Americans.

Thus, meaningful action will not take place without effort, Rothstein and his daughter Leah wrote in their new book, “Just Action.” They call for the sort of local activism typified by the civil rights campaigns of the 1960s.

“What we require are actions as powerful to diminish segregation as those that created it,” the Rothsteins wrote in “Just Action.”

The impact of racial discrimination in housing is still felt today in that similar homes in segregated Black neighborhoods are valued less than identical homes in white neighborhoods, Rothstein said.

Some possible solutions

Solutions need to be just as broad as the discrimination that created these inequities.

Since homes are a major wealth generator in the U.S., an inheritance tax could help to rectify the impact of this massive discrimination. A recent New York Times article noted that in the next 20 years or so, about $84 trillion will be passed to the next generation, the largest wealth transfer in American history. If just 1% of that income were taxed to rectify this discrimination, it would produce $840 billion for such uses as fully funding Section 8 housing or for mortgage subsidies in low-income neighborhoods.

And how about reforming credit to allow rental payment history to be used in credit scores? Because fewer African Americans own homes, they don’t have mortgage payment histories.

Banks could also subsidize African American home buyers. A 1976 federal law allows lenders to provide mortgages to Blacks on more favorable terms to remedy previous discrimination, but it is rarely used.

In “The Color of Law,” Rothstein also suggests that the federal government could purchase 15% of the homes that come up for sale in developments that were racially restricted, like Levittown on Long Island, and then sell them to African Americans at rates their grandparents would have paid if allowed to do so.

He also suggests that the real estate industry donate a portion of its commissions to create a $20 billion annual fund to support Black homeownership.

He also emphasized that affordable housing refers to more than housing for the very poor. Most African Americans are not poor but are working-class people; they are part of the “missing middle.”

Middle-class neighborhoods are disappearing. Thirty years ago, two-thirds of Americans lived in one; now only about half do.

What Jacksonville could do

The point is that in order to rectify discrimination created for racial reasons, solutions must be designed racially, as well, Rothstein said. Solutions also must be local.

As a role model, Rothstein pointed to a New York Times article on Montgomery County, Md., a Washington, D.C. suburb, which has built public housing over several decades. Its local housing organization acts as a developer and a financing agency. About 2,000 housing units have been built there for moderate-income residents outside federal housing programs.

By selling bonds to finance projects, it can lend itself funds and pay itself interest.

Jacksonville, on the other hand, has a history of putting forth ideas to build affordable housing, through years of studies and committee reports. Funding is generally cited as the roadblock to implementation. But we could do something like Montgomery County. Where could the seed money come from? How about making it part of the stadium negotiations with the Jacksonville Jaguars? An initial investment from the Jaguars could be the boost this city needs and would certainly reduce some of the opposition involved in the proposed $1 billion city investment in a new football stadium and entertainment district.

We could also reform zoning. Eliminate or reduce single-family zoning. Encourage inclusionary zoning that requires a certain percentage of affordable homes — something like 10% to 25% — included in new developments.

While most Americans played no direct role in redlining, white Americans still benefited from it. As Rothstein wrote in “The Color of Law,” most Americans accept the privileges we did not earn, so by the same token we should accept the duty to correct the inequities we did not commit. The people of Jacksonville and our elected leaders need to recognize the impact of racial discrimination that is built into the nation’s banking, real estate and justice systems. Jacksonville residents are still suffering from the impacts of redlining. As the benefits of consolidated government largely bypassed the redlined communities in Jacksonville, the inequities remain, what King called a bad check marked “insufficient funds” in his “I Have a Dream” speech.

Strong local action is needed to rectify this. A sense of outrage is required and justified.

Mike Clark devoted about 47 years to Jacksonville's two daily newspapers. He retired in 2020 after 15 years as editorial page editor at The Florida Times-Union, where he and his staff won local, state, regional and national journalism awards.

He is the author of the new book, “Civil War Survivor: Incredible True Story of a Union Private.”