In honor of National Hispanic Heritage Month, here are nine stories that suggest Hispanic influence on the development and culture of Jacksonville is just as old as the city itself.

Datil peppers

Datil peppers are a small, waxy, and extraordinarily hot variant of the habanero-type pepper, Capsicum chinense. Many farms, gardens and front porches around the First Coast grow these legendary peppers – in fact, they’re so common that many locals don’t realize they’re a heavily localized variant that’s basically unknown anywhere else.

Two rival origin myths attribute the arrival of the datil pepper in St. Augustine to different groups with centuries of history in the First Coast: the Cubans and the Minorcans. Florida’s Cuban connection dates to the earliest days of Spanish colonization in the 16th century. The Minorcans, from the Spanish Mediterranean island of Menorca, came to Florida to settle the New Smyrna colony in the 18th century. When this venture failed, the Minorcans relocated north to St. Augustine, where their descendants number about 25,000 across St. Johns County today.

Datil peppers have long been part of local Minorcan cuisine, lending credence to the story that they brought it over. However, the peppers aren’t grown in Menorca; they’re habanero-type peppers native to the Caribbean and Central America – “habanero” refers to Havana, Cuba. A 1937 St. Augustine Record article confirms that datils were first brought to St. Augustine from Santiago, Cuba, around 1880 by jelly maker Esteban B. Valls. The peppers thrived in Valls’ garden and quickly became popular around town, with the Minorcan community embracing them as their own. Today, datil peppers are common in dishes, sauces and marinades all over the First Coast.

Minorcan chowder

Minorcan chowder is a local dish popularized by the Minorcan community of St. Augustine. The Minorcans, from the Spanish Mediterranean island of Menorca, came to Florida to settle the New Smyrna colony in the 18th century. This thick soup comprises a red broth thickened and colored by tomatoes and tomato paste, supplemented with potatoes, vegetables and chopped clams or other seafood. The dish derives from the Mediterranean cooking traditions of Minorca, where hearty tomato soups were popular with sailors and fishermen. As a chowder with a tomato base, Minorcan chowder is most similar to Manhattan chowder, rather than the venerable New England clam chowder made with milk and cream. The distinguishing feature of Minorcan chowder is the datil pepper, which gives it a scorching heat with a touch of sweetness. Today, Minorcan chowder can be found not only in St. Augustine but in Jacksonville and elsewhere around the First Coast.

Old Town Fernandina

Located just north of Downtown Fernandina, Old Town holds the distinction of being the last Spanish city platted in the Western Hemisphere. Platted in 1811, the plat is based on the 1573 Law of the Indies. This was a document the Spanish used to organize new towns they settled as a result of their explorations.

Old Town served as the original town site of Fernandina until David Levy Yulee platted a “new” Fernandina during the 1860s, shifting the center of the town from Old Town to its present location. Roughly bounded by Bosque Bello Cemetery, Nassau, Marine, Ladies and Towngate streets, Old Town was added to the U.S. National Register of Historic Places as a historic site on January 29, 1990.

Jacksonville’s short-lived Cuban cigar industry

Commercial cigar rolling in Florida dates as far back as the 1830s. Seeking to market authentic Cuban cigars in America, while avoiding high tariffs from Havana and Spanish trade restrictions, Samuel Seidenberg opened the first cigar factory in Key West in 1867.

Late 19th century cigar makers also found Jacksonville an attractive location to process Havana tobacco. At the time, Jacksonville was the terminus of six railroads, home to a deep river channel, and considered the gateway to Florida, the Bahamas, and Cuba. Most of Jacksonville’s cigar makers were clustered in two areas within walking distance: East Bay in the vicinity of Liberty Street and West Bay in the vicinity of LaVilla’s Broad Street.

By 1895, Jacksonville had become home to 15 cigar manufacturing companies and thousands of Cuban immigrants. Its largest, Gabriel Hidalgo-Gato’s El Modelo Cigar Manufacturing Co., employed 225 and produced 6 million stogies annually. However, City Council member José Alejandro Huau, Hidalgo-Gato’s brother-in-law, may have been the most popular cigar factory owner in town. Employing 150 workers at his own West Bay Street factory, Huau was influential in José Martí’s visiting Jacksonville eight times between 1891 and 1898 to stir up enthusiasm and financial support for Cuba’s freedom movement.

Jacksonville’s budding hand-rolled cigar industry eventually declined with the emergence of Tampa’s Ybor City. In addition, following Cuba’s independence, many Cubans living in town returned to the island.

Camp Cuba Libre

In May 1898, a military installation known as “Camp Cuba Libre” was established in Jacksonville for the deployment of American troops in Cuba during the Spanish-American War. Within a few weeks of its establishment, trainloads of soldiers were arriving, and by the end of the war, as many as 30,000 troops had come through Camp Cuba Libre under the command of Major General Fitzhugh Lee, Robert E. Lee’s nephew. Said to be a prankster and practical joker, Fitzhugh Lee was a West Point graduate who had also served in the American Civil War as a Confederate officer.

Lee selected the location of Springfield as the camp site because of its relatively high elevation and sandy soil, which alleviated the sewage problems prevalent at camps in other communities located at lower waterfront elevations. In addition, the Daughters of the American Revolution Hospital Corps contracted Catholic nuns as nurses, who were sent to the camp prior to being assigned to another camp in Havana.

After the official end of the Spanish-American War in April 1899, Major General Fitzhugh Lee would go on to become the military governor of Havana and Pinar del Rio. Originally known as Camp Springfield, Following the Great Fire of 1901, much of the land that was once occupied by Camp Cuba Libre was developed into the present-day neighborhoods of Springfield and Eastside.

Downtown’s haunted El Modelo block

While the Spanish-American War and the Cuban cigar manufacturing scene in Jacksonville are no more, there is a ghostly story that lives on. Located in LaVilla at 501 W. Bay St., the El Modelo block is one of a handful of sites Downtown that survived the Great Fire of 1901. Originally built in 1886, during its early years, the structure was occupied by Gabriel Hidalgo Gato’s El Modelo Cigar Manufacturing Company. Hidalgo-Gato’s company was the largest cigar manufacturer in town, employing 225 and producing 6 million stogies annually at its height. A beacon of Jacksonville’s early Cuban community, the site was visited by José Martí multiple times during the 1890s.

After Gato’s death, the building was occupied by the Plaza Hotel and a number of bars in what became a seedy area of the city. In 1907, a Spanish-American War veteran entered the front door of one of these bars in what would be his last act. He was immediately shot in the chest with a sawed-off shotgun. Upset over the tragic event — and still waiting on that drink — the victim’s ghost allegedly continues to haunt this building.

Downtown and the Panama Canal

During the 1850s, Jacob Brock established Jacksonville’s first shipbuilding operation on a waterfront site on East Bay Street, just east of Catherine Street. After Brock’s death in 1877, the shipyards were sold to Alonzo Stevens. The Merrill-Stevens Engineering Co. was formed in 1887, when James Eugene and Alexander Merrill joined Stevens as business partners. Between 1902 and 1914, the shipyard built barges on site that were used in the construction of the Panama Canal. During the time the Merrill-Stevens Co operated the shipyard, it was home to the largest dry dock between Newport News, Virginia, and New Orleans. By the opening of the Panama Canal, employment had increased to 1,500 workers.

During the 1950s, Merrill-Stevens sold the shipyard and relocated to Miami, where the company still builds yachts today. In 1963, new owner W.R. Lovett renamed the company the Jacksonville Shipyards, Inc. (JSI). By the time JSI was sold to Fruehauf Corp., it had become Jacksonville’s largest civilian employer, with a workforce of 2,500. JSI’s decline began in the 1980s, shutting down briefly in 1990 and laying off 800 workers. It would reopen briefly, only to close permanently in 1992 after selling its drydocks to a shipyard in Bahrain. Today, much of this former industrial site related to the construction of the Panama Canal is planned to be transformed into a riverfront park and cultural district.

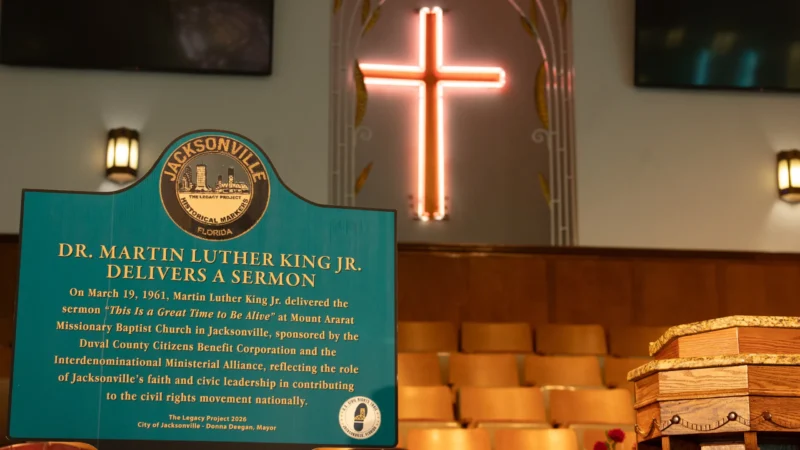

LaVilla and integrating professional baseball

A historic trade partner with the capital of Puerto Rico, Jacksonville sees 90% of the goods shipped between the mainland and the island come through its port. As a result, San Juan was declared a sister city in October 2009. Historically lumped into the generic term “African American,” Afro-Puerto Ricans were an important part of Jacksonville’s segregation-era Black community evolution as a place for jazz, blues and landmark civil rights events. For example, a Puerto Rican-born pillar of Black society, Manuel Rivera, operated Ashley Street’s Manuel’s Tap Room, a lounge and grill that was open 24 hours a day during the 1940s and 50s. Described by the NAACP as “the finest of its kind in the South,” Manuel’s hosted many up-and-coming jazz musicians, including Ray Charles before he found international fame. Overcoming Jim Crow, in 1953, Rivera also opened his home to three young Black Jacksonville Braves baseball players, Puerto Rican-born Flex Mantilla, Hank Aaron and Horace Garner, thus integrating Major League Baseball in the deep South.

Rapidly diversifying neighborhoods

-L.jpg)

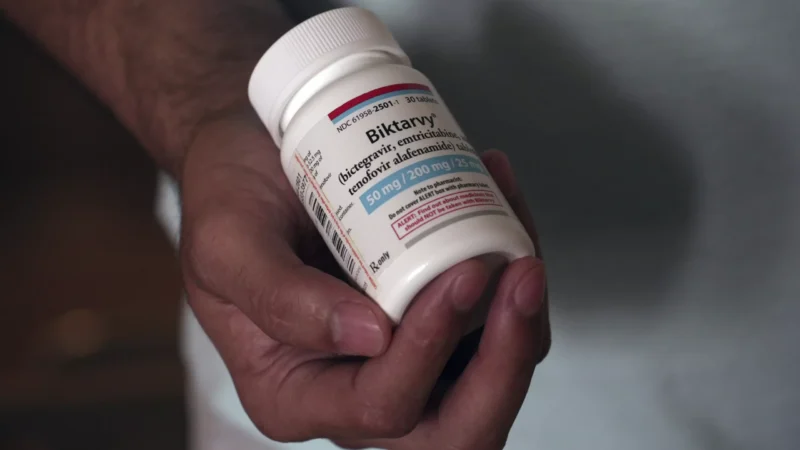

Duval County’s Hispanic population increased from 2.6% in 1990 to 11.3% in 2020 and even further since then. As a result, the cultural makeup, development pattern, and flavor of long-established neighborhoods across the city continue to evolve. Today, tens of thousands of people of Latin and Caribbean descent, including from Mexico, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, and Venezuela, are living in town and reshaping their neighborhoods, such as the Westside’s 103rd Street corridor and Spring Park near Englewood.

Contact Ennis at edavis@moderncities.com