Since she arrived in Jacksonville in 2021, Chief Resilience Officer Anne Coglianese has been in fact finding mode, getting to know her new home and the threats facing it. Now she’s sharing what the data show so far and preparing for a series of public meetings that will help shape the city’s resilience strategy.

In addition, the city is hiring a firm to help evaluate its land development regulations, which she says could reveal regulatory opportunities to address climate-related threats.

In 2022, Coglianese worked with about 30 consultants from across the country, a number of them based in Jacksonville. “What we’ve spent the better part of the last year doing is really quantifying the risks and vulnerabilities that are facing Jacksonville,” Coglianese told members of the City Council’s Neighborhoods, Community Services, Public Health and Safety Committee last week.

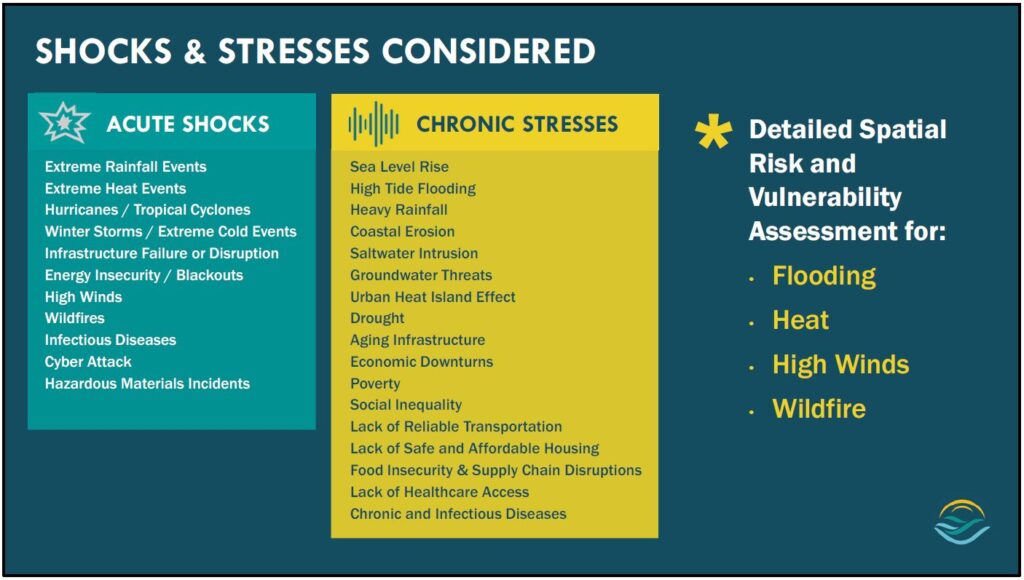

Flooding, heat, high winds and wildfire risks are expected to worsen because of climate change, with wind and wildfire risk assessments ongoing. “These are hazards that happen way less frequently, but when they do they could really disrupt Jacksonville, so we also want to make sure that that’s on our radar,” she says.

Flooding

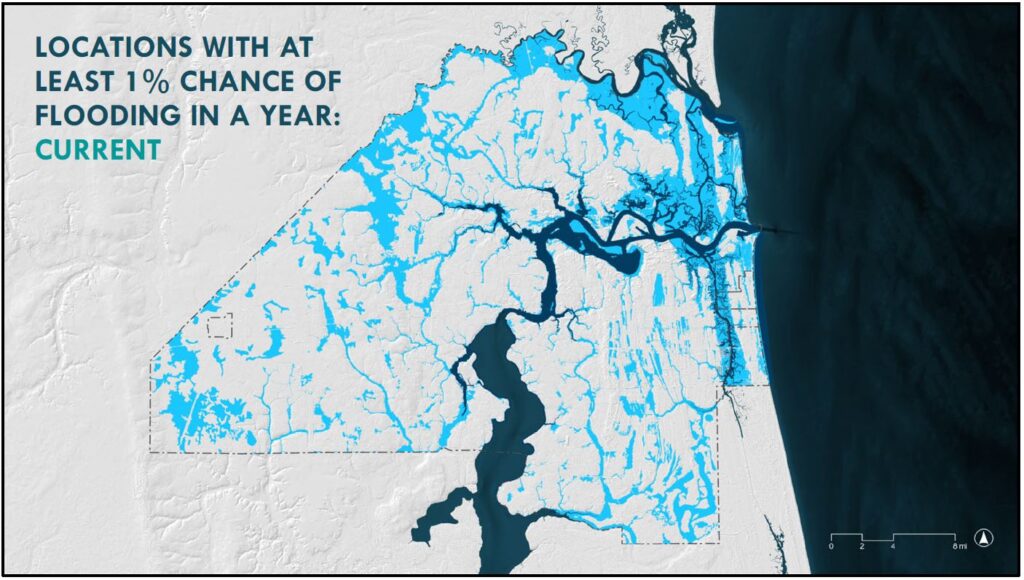

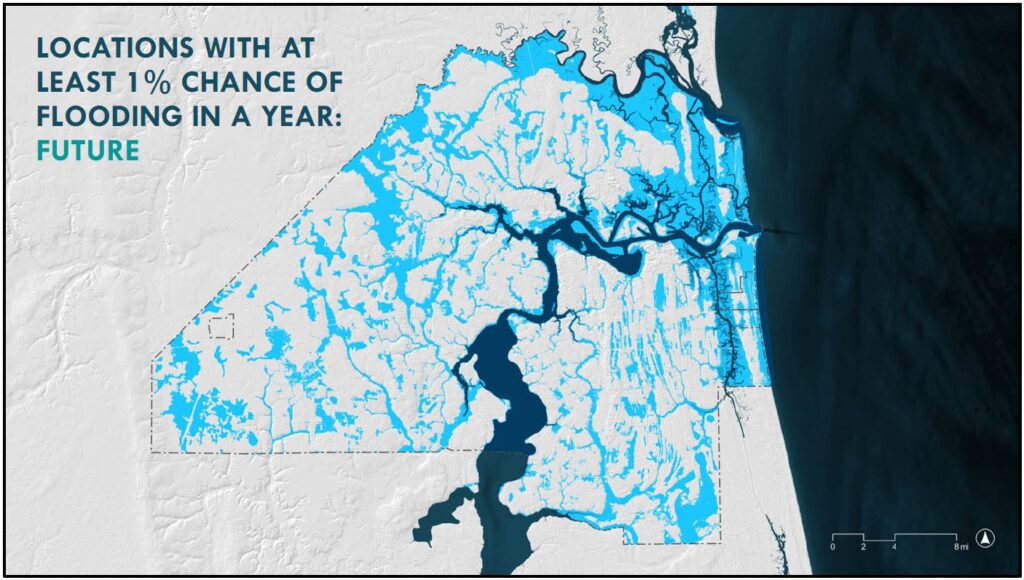

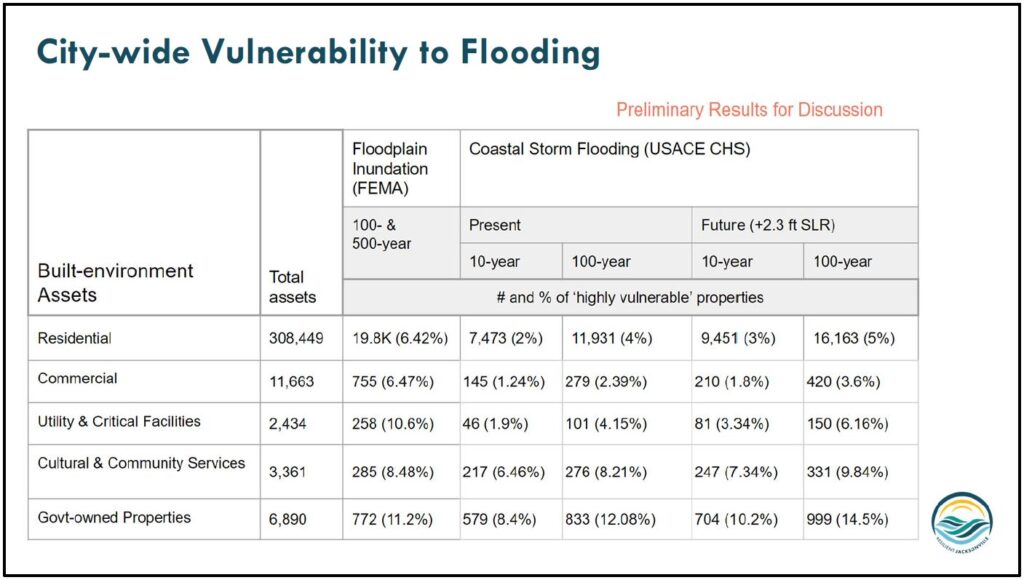

The city could see twice as many extreme rainfalls by the year 2070 and 40 to 60 high tide flooding days by 2050, up from just four in 2021. Northeast Florida could also experience as much as 2.3 feet of sea level rise by 2060, which would exacerbate both coastal and river flooding.

The city’s modeling up to this point has been focused on high-tide flooding and coastal storm surge, but Coglianese and her partners have also been trying to model compound flooding — when different types of flooding happen at the same time, like when coastal storm surge mixes with rivers swelled by heavy rain.

“This is also an area where the field of hydrologic modeling is really trying to get even more precise,” she said. “In the coming years, this is probably an area where we look to reassess our models and use new best practices.”

The good news: While flood-risk projections show a big threat to the area around Downtown Jacksonville, Coglianese stresses that current predictions don’t account for planned interventions.

For one thing: “All of the Downtown bulkheads are being replaced and are being elevated and being designed in a way with adaptive capacity so that they can be kept to higher levels in the future.”

Heat

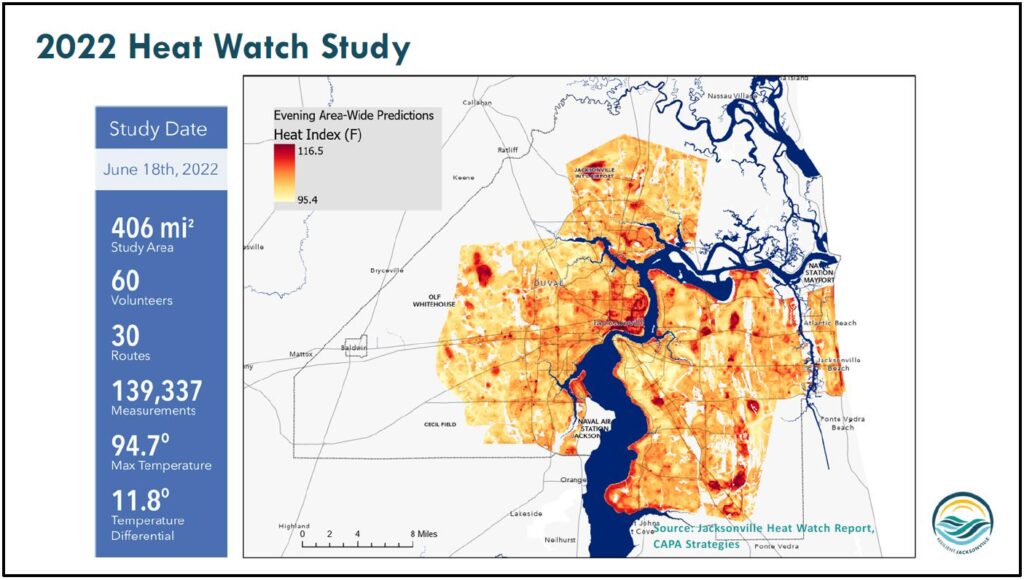

Over the last summer, the Curry administration worked with the University of North Florida to conduct a large-scale urban heat mapping study. Around 60 volunteers ran 30 routes around the city with sensors attached to their cars, gathering heat and wind data, which have been aggregated into a heat map.

“It really shows that, depending on where you’re standing in Jacksonville, you could experience a 12-degree difference in the temperature, which we know has a key correlation to public health,” Coglianese says.

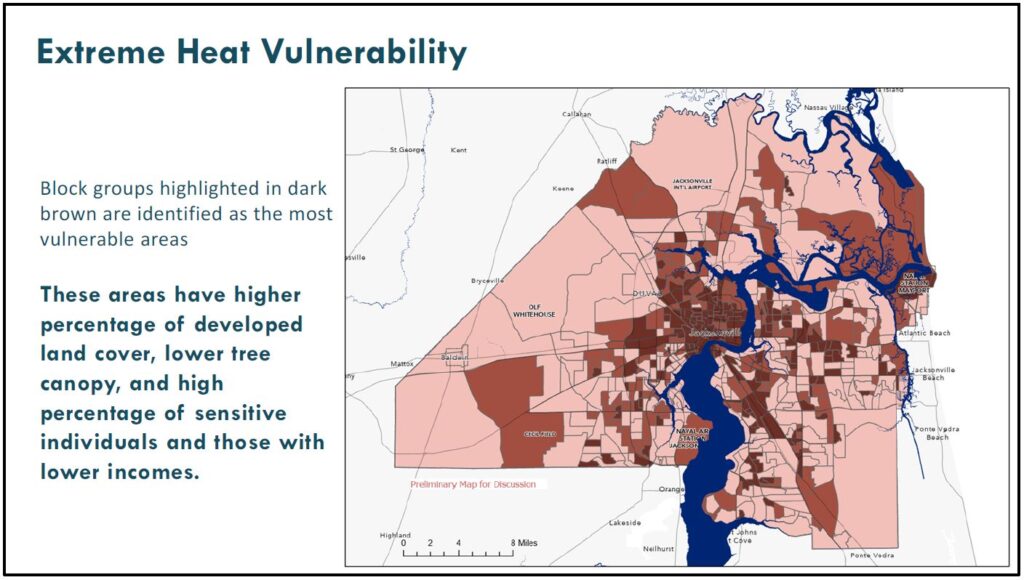

Hotter areas of the city tend to have more buildings, roads and parking lots and fewer trees. Many are in and around low-income neighborhoods.

Like flooding, extreme heat is a growing risk in Jacksonville. By the time today’s babies are adults, Jacksonville could see about 40 more days per year with heat index values above 90 degrees. Our region could also experience an additional 50 to 100 warm nights (above 75 degrees) by 2050. “If the human body can’t cool off at night, that’s when you really see the high rates of heat-related illnesses spike,” Coglianese says.

Extreme heat is the deadliest weather-related risk in the U.S., and it affects education outcomes, workforce productivity and quality of life.

Vulnerability

The city is working to take all of its new data on flood and heat risks and layer it in with what’s called vulnerability to paint a clearer picture of risk in specific parts of Jacksonville — all the way down to the single-building level.

To assess heat vulnerability, the city is considering factors like Census data that show where there may be concentrations of vulnerable populations — people older than 65 or younger than 5.

“This can, once again, help us with long term planning, making sure that we’re putting in green features, cooling features in areas of the city where we know there’s an extreme vulnerability,” Coglianese says.

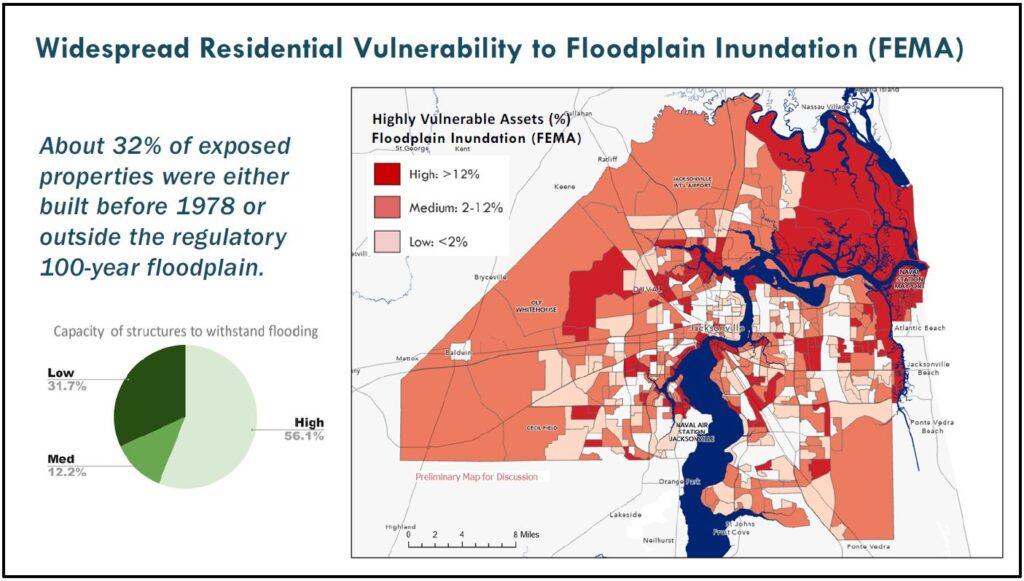

Assessing flood vulnerability can mean considering factors like the location of a building within a parcel and the year it was built.

The study is focusing on utilities and other critical services, as well as commercial properties and homes — plus, the city’s roads, which, if compromised, could leave neighborhoods isolated during a major flood.

“We’ve been able to look at how they’ll perform and how vulnerable they are under different types of storm events,” Coglianese says. “This will really help us as we get into planning”

When the city layers social vulnerability data on top, it’s apparent that vulnerable properties in Jacksonville are often in areas that have the highest percentage of households with incomes below the poverty level.

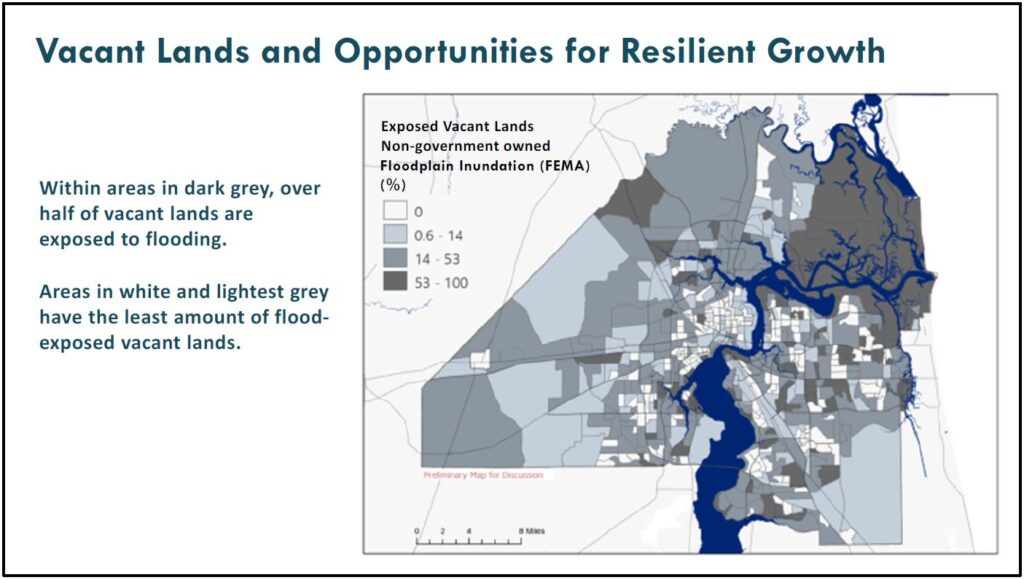

Coglianese and her partners are also looking closely at the flood exposure of vacant land. This will allow them to identify the areas where development should be discouraged due to high flood risks.

“But it also really shows us where we have an opportunity, where we have high and dry land, where we have places that are low hazard and how we can start to cluster and provide incentives for the type of dense development we want to see in areas that we know are going to be safe and vibrant and healthy, long term,” she says.

Interventions

Now that the city has a better idea of its risks and vulnerabilities, Coglianese’s team is starting to explore various interventions that could lessen our risks. There are two main ways the city is doing that: through ongoing working groups with subject matter experts — sessions on everything from land use and development to critical infrastructure and emergency services — and an upcoming series of public meetings.

The three public meetings will be held next month throughout the city, all at 6 p.m.:

- Feb. 9 at the Legends Center, 5130 Soutel Dr.

- Feb. 13 at the Edward Ball building, 214 N. Hogan St.

- Feb 16 at the Southeast Regional Library, 10599 Deerwood Park Blvd.

“Once we have all of the opportunities, all of the ideas that we’ve heard from the public, that we’ve heard from experts, we’re then doing an alternatives analysis where we take the data sets and we start to weigh the pros and cons of different options and start to see solutions emerge,” she says. “We’re going to be really guided by the data. But also, it’s so important for that data to be grounded by what we’re hearing from people who are living in these neighborhoods.”