When University of North Florida biology Professor Adam Rosenblatt moved to Jacksonville in 2017, it seemed like no one was talking seriously about climate change at City Hall. “Now those conversations are happening frequently, at least as far as I can tell,” he says.

Rosenblatt, a co-founder of the local chapter of the Citizens Climate Lobby, attributes that shift to the hiring of Jacksonville’s first Chief Resilience Officer, Anne Coglianese, who’s now partnering with him on a city-wide heat mapping project.

Volunteers are needed to help with it, some time between June 6-19. That means attaching sensors to their cars and driving specific routes throughout the city multiple times a day, every day for a week. At the end of that week, all the data collected will be aggregated to show which neighborhoods in Jacksonville are most threatened by extreme heat — the deadliest form of hazardous weather, according to the National Weather Service.

“The city is partly funding the campaign with $20,000. We’ve gotten support from the city’s PR team, and Anne has been very generous with her time,” Rosenblatt tells ADAPT. “Once the study is complete I’m looking forward to sharing the results as widely as possible and helping the CRO use the heat data to inform the city’s resilience strategy.”

To do the study, the city received a $13,000 grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. It’s one of the city’s four major “resilience” projects that have collectively attracted millions of dollars in state and federal funding this year alone, Jacksonville Chief Resilience Officer Anne Coglianese says, and her office is aggressively pursuing more.

“Resilience” generally refers to governments’ preparations for the impacts of climate change — actions that are increasingly urgent in Florida at the state and local levels. About a year ago, Gov. Ron DeSantis signed into law a package called the Resilient Florida Program, which included grants for local governments to do their own projects.

Last month, under that program, Jacksonville was awarded $500,000 for an ongoing citywide flood vulnerability study, mapping high-hazard areas along the Atlantic coast and St. Johns River. The study, which will cost upwards of $600,000 total, is expected to be finished by September of this year, with its data meant to help city staff base decisions on projected future risks.

“We’re not only looking at our current condition, but also what we expect that flood risk to look like at 2040, 2070 and 2100,” says Coglianese.

Back in January, Jacksonville was also awarded Resilient Florida grants for two infrastructure projects. A $20 million grant is helping add a storm water pump station at LaSalle Street in San Marco. LaSalle Street and the surrounding residential area frequently experience flooding during heavy rains — the neighborhood’s homes and businesses took on feet of water after Hurricane Irma in 2017.

In addition to the pump station, this project — which will cost approximately $40 million — will incorporate back-flow prevention technology to help counter the effects of tidal and stormwater flooding as well as sea level rise. Improvements will also be made to the drainage-collection systems in the area to ensure that floodwaters can quickly move to the pump station.

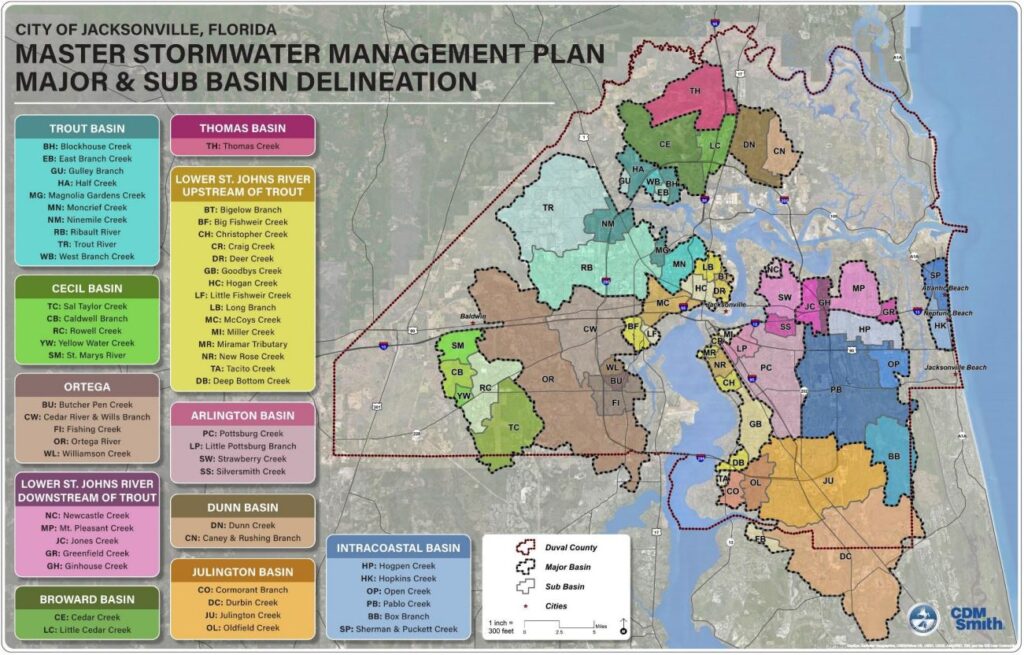

Another Resilient Florida grant of almost $1.4 million will help dredge the Westside’s Wills Branch Creek, which was identified in the city’s Master Stormwater Management Plan as a “primary drainage pathway.” By deepening a downstream section of the creek, this project should provide relief for nearby residents, who are used to floods.

All told, “By the end of the summer or early fall, we will have not only a map of our flood risks, but also a map of how climate might be impacting extreme heat across Jacksonville,” says Coglianese. “We’ll be able to layer these two data sources together and fold in some Census data so that we have a complete picture of what vulnerability looks like in Jacksonville.”

To do that, the city is working with consultants on a tool called AccelAdapt, which will give a better picture of vulnerability that includes economic and social factors.

AccelAdapt could allow business owners, for example, to look at a storm and flood risk where most of their employees live, or on the roads their customers take most often.

“This tool will give us really granular, almost parcel-by-parcel data on risk that we, as a city, can then use to make decisions about infrastructure and programs,” Coglianese says.

The city’s internal-use version of the AccelAdapt portal should be ready by early fall, with a goal to eventually create a more easily understandable public-facing version.

Next, the city of Jacksonville is also looking to tap into another pot of state funding: $100 million through the Statewide Flooding and Sea Level Rise Resilience Plan. Local governments must have completed their own flood vulnerability assessment to qualify.

Coglianese says, “We’re hoping that by moving very aggressively on this vulnerability study, we’ll be able to, as quickly as possible, qualify for that additional pot of funding.”

The city has also applied for funding from FEMA’s Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program and the National Coastal Resilience Fund, a partnership between the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and NOAA.

“We’re not letting a single grant opportunity slip by us,” Coglianese says. “We are making note of every time there’s a Notice of Funding Availability and we are either identifying a project that’s already in our capital improvement plan, or we’re looking at the grant requirements and coming up with a project that we feel will check as many boxes as possible so that we’re really taking advantage of the resources that are available right now.”

Additional federal funding for resilience projects should be available soon through the bipartisan Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act. “In the coming years, I think those federal sources will also be significant and in the mix of what we’re using to fund resilience projects,” says Coglianese.

All of this work will ultimately be turned into a comprehensive resilience strategy highlighting actions the city can take to defend against the effects of climate change. It will be developed in consultation with various city departments, independent authorities, City Council and stakeholders including the business community and residents.

Rosenblatt says developing that resilience strategy is an important first step. “Hiring a CRO — and especially someone like Anne — shows that the city is serious about confronting the threat of climate change,” he says. “Of course, what really matters is what the mayor and City Council decide to do with the climate resilience strategy produced by the CRO. If they develop significant policies related to resiliency efforts and dedicate serious dollars toward actually following the strategy, then it will show that hiring a CRO wasn’t just for show. I’m optimistic that will be the case.”

And Coglianese says the city won’t wait until that strategy or all of these studies and reports are done to start working on resilience. For example, Coglianese says the city needs to update its land development regulations, which determine what kind of development is being permitted, and where. Coglianese says the city will seek input from developers and the community before any changes are made.

Also, “We’ll be working with the Department of Public Works to update design standards to make sure that every city project is considering climate and is considering future projections of risk in how they’re designed from the get go so that every dollar in our capital improvement plan, at some step in the process, has been considered for climate risk, just to make sure we’re making the smartest financial decisions in construction,” Coglianese says. “We don’t want to wait until the final strategy is published before we start tackling these very big questions.”