New research out of the University of Florida suggests that stormwater ponds, specifically permanently wet retention ponds, are a significant source of climate change-causing greenhouse gas emissions.

Stormwater ponds are man-made ecosystems that are used to help reduce flooding and pollution from runoff. The St. Johns River Water Management District, which establishes water quality standards in the Jacksonville area, has issued tens of thousands of permits for them over the past several decades.

Stormwater ponds are the most commonly used stormwater system in the U.S., and Florida has more than 76,000 of them, covering an estimated area of nearly 260 square miles.

While stormwater or retention ponds do provide ecosystem benefits — as they were designed to — the new research from UF indicates they may in fact be delivering a net disservice by contributing to greenhouse gas emissions.

The amount of greenhouse gasses emitted appears to be linked to several factors, including the age of the pond.

“We found that in younger ponds, their rate of carbon burial was low and the rate that they were emitting carbon to the atmosphere was quite high,”said PhD student Audrey Goeckner, the lead author of the study. “Older ponds seem to be storing carbon in their sediment more rapidly and emitting less carbon gas to the atmosphere.”

Stormwater ponds tend to accumulate organic matter, like leaves, algae or manure. That material eventually settles at the bottom.

“That would be called carbon storage [or carbon burial], or the carbon coming from those organic materials that’s in the stormwater,” explains Mary Lusk, assistant professor in the Soil and Water Sciences Department at UF. “But as it sits there with time, those organic materials can begin to decompose and break down, and as they do, they give off those gasses of carbon dioxide and methane.”

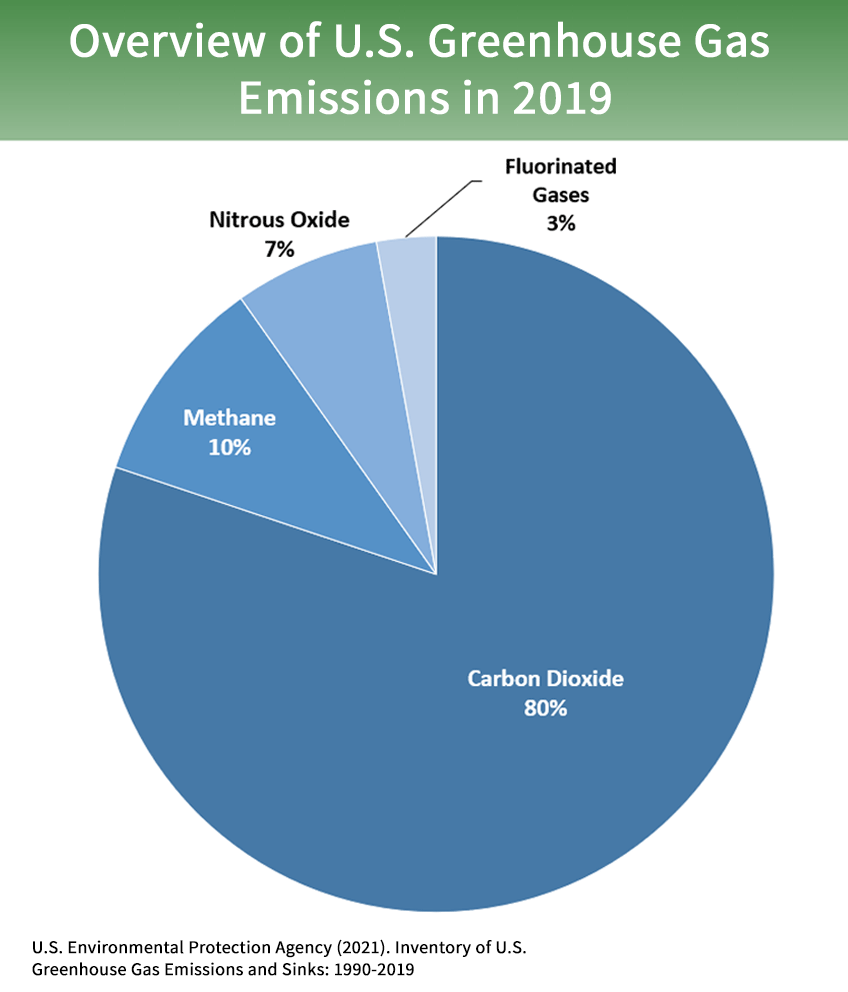

Carbon dioxide — what we exhale — is the most prevalent greenhouse gas in the atmosphere, and its excess is considered the leading driver of climate change.

Another factor that determines how much C02 stormwater ponds emit is acidity, which lessens over time.

“That’s a natural process that happens, and the more that pH goes up, the more we can keep carbon dioxide in the water,” Lusk says. “But at lower pHs (higher acidity), when these ponds are younger, chemically what goes on is that carbon dioxide is more likely to escape from the water.”

A couple of things are at play in reducing acidity over time. First, in urban environments, stormwater runoff tends to pick up calcium carbonate from concrete as it flows through underground piping systems and into stormwater ponds. Also, as ponds get older, they tend to collect nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, which fuel the growth of algae. Algae’s photosynthesis (turning sunlight and carbon dioxide into food for itself) both reduces the amount of carbon dioxide in that ecosystem and reduces acidity.

These natural processes that lower emissions could be an inspiration as local governments start thinking about how stormwater pond management is linked to climate change. But Lusk warns there’s still a lot that needs to be studied before we know best practices.

“This is the first study that I know of that anybody has done to look at this in stormwater ponds. So I was really excited that Audrey [Goeckner, PhD student] worked on this and that she did such a great job with it,” she says. “It’s almost like now we’ve identified what’s going on, so now we need to get out there and do some research on how we can mitigate that a little bit.”

For now, the St. Johns River Water Management District requires stormwater ponds in the region to be regularly inspected and maintained. But some of their recommended practices, like dredging and the use of pesticides, can actually exacerbate emissions.

For example, algaecides are frequently used to treat algal blooms in ponds.

“You don’t have as many photosynthesizers in the water column to utilize the CO2 because you just killed all of them,” Goekner said.

On top of that, methane is produced in conditions with no oxygen, so if you have a lot of organic matter (dead algae) that’s depleting the pond’s oxygen, you might see more methane being emitted too. Methane is about 86 times more potent than carbon dioxide at warming the atmosphere over a 20-year period.

“I think what we’re advocating for really in this research is for the climate science and the carbon science community to recognize that these ponds can definitely be huge sources of greenhouse gasses, and that we ought to include those in our models of statewide and regional and even global carbon cycling so that we can better constrain how carbon is cycling in our urban environments,” says Lusk.

In the meantime, Goeckner hopes more scientists will start talking to developers and the engineers that design stormwater ponds.

“There are so many in the state of Florida and they continue to be built as more people move into our state,” she said. “We should be asking more questions, like, ‘How do our constructed spaces influence the way that carbon is moving through the landscape?’ Because it all plays a part in climate change.”

Fara Ilami, the Regional Resiliency Manager for the Northeast Florida Regional Council, agrees with that assessment.

“This research highlights the need for effective balancing of competing environmental needs and for constant incorporation of new findings into urban planning processes. Accurate modeling of consequences for new stormwater pond installation and maintenance of older stormwater ponds should be developed for land managers to use when making these types of decisions,” she said. “Here in Northeast Florida, we have a considerable amount of salt marsh which serves as a carbon sink; perhaps the contribution of greenhouse gasses by stormwater ponds might not alter the net carbon budget for this region as much as in other parts of Florida, due to the amelioration by the salt marsh. It is crucial to find out the answers to questions like this before making environmental changes.”