The World Affairs Council of Jacksonville has invited physicist Steven Koonin, a New York University professor, to speak about his book, Unsettled: What Climate Science Tells Us, What It Doesn’t, and Why It Matters, on Tuesday, Jan. 25, at the Ponte Vedra Inn & Club.

Koonin’s background is impressive — he was part of a team of scientists credited with debunking the University of Utah’s claim to have discovered “cold fusion,” which, if true, would have transformed the energy landscape. But when it comes to climate change, many of Koonin’s views — as expressed in his book and in prior speaking engagements — are controversial because they don’t line up with the scientific consensus.

“In keeping with the World Affairs Council’s mission to promote understanding of issues of global importance, to deliver knowledge on complex subjects behind today’s headlines, and to present diverse viewpoints, we look forward to hearing Dr. Koonin’s perspective and to the dialogue among members of our community,” Trina Medarev, executive director and CEO of the World Affairs Council of Jacksonville, wrote in an email to ADAPT. “This ability to connect citizens to content, to which we might agree or disagree, is indeed an opportunity to experience lifelong learning and actively engage in matters of civic importance, improving the quality of our lives and our community.”

Climate scientists, science communicators and journalists who spoke to ADAPT say the contributions he’s making to the dialogue on climate change are unproductive. They are critical of the World Affairs Council’s decision to invite Koonin to speak without someone on hand to challenge statements he makes that aren’t in line with the scientific consensus, and they hope the nonprofit will invite an established climate scientist or climate communicator to speak in the future.

What’s driving climate change?

Koonin and the vast majority of climate scientists agree, for the most part, on the basics of climate change. “I think it’s very difficult not to acknowledge that the climate is changing and that humans are exerting a growing influence on it,” Koonin said in an interview with ADAPT.

Koonin does downplay the role of human activity. “Human influences are physically small. They’re therefore confounded with a number of other influences that cause the climate to change,” he said.

Climate scientists, on the other hand, say there are no natural factors that could explain the rate of global warming that’s been observed over the past 150 years or so.

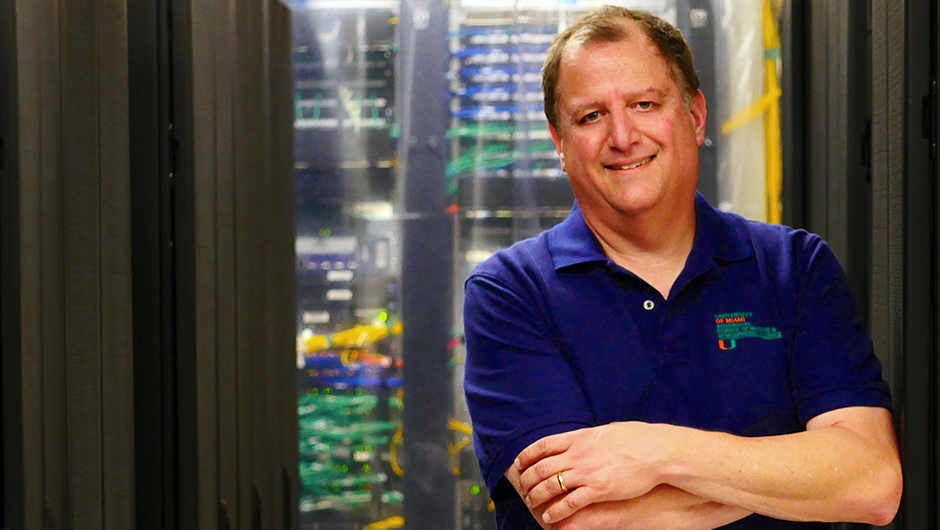

“We can’t ignore one simple fact, and it’s a fact, it’s indisputable: If you go back 800,000 years, the CO2 in the atmosphere has gone up or down from 200 parts per million by volume to 300 parts per million by volume,” says climate modeler Benjamin Kirtman, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the Rosenstiel School for Marine and Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Miami. “We’ve effectively gone from 300 to well over 400 [parts per million by volume] in 150 years. So not only are we out of bounds of what’s happened in the last million years… we did it in 150 years, whereas that kind of jump usually took 10,000 to 40,000 years. So you just can’t ignore that humans are having this enormous impact on the climate system.”

That human impact comes from the burning of fossil fuels, according to Scott Denning, professor of atmospheric science at Colorado State University. “Digging up carbon and setting it on fire is incredibly destructive and we have to stop doing it so we, the humans, can be fine,” he said.

Is climate change fueling stronger hurricanes?

When it comes to the impacts of climate change, Koonin’s views also diverge markedly from mainstream science. Hurricanes, for example, are a major concern in Florida, and climate scientists say rising global temperatures are fueling stronger storms. However, Koonin appears to disagree with that interpretation.

“There have been no detectable trends in hurricanes over 100 years. There have been ups and downs of course, but over a long term, not much,” he said. “There is a hint that the fraction of hurricanes that are the strongest has increased in the last 30 years, but then there are other papers that came out subsequently that said, ‘No, no, it’s just a return to natural variability.’”

According to Kirtman, who was a lead author for the fifth U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report in 2014, Koonin’s take on hurricanes is inaccurate when you look at the best available science.

“We know quite convincingly, there’s a high degree of confidence, that we’re seeing more category 4 and 5 storms. It’s also compelling that climate models themselves are predicting more category 4 and 5 storms. So the total storm counts, yes, there’s not a trend in the number of storms, but there is a trend to more powerful storms,” he says. “There’s also some compelling but somewhat more uncertain evidence that storms are producing more rainfall and have slower forward speeds. And so both of those things combine to increase the flood risk.”

Is climate science unsettled?

One of Koonin’s main criticisms of climate science is in the title of his book. He claims the science is “unsettled,” and because of that uncertainty he believes governments should be cautious about pursuing solutions.

“The policies that we make have to be a balance between what we know about the science and possible risks against all of the other implications of policy,” Koonin said. “If you decarbonize too rapidly, you will incur costs associated with disruption and with deploying immature technologies. If you decarbonize too slowly, you incur these probabilistic costs due to an increased risk of bad stuff happening with the climate. And so there’s an optimal that balances these two.”

Whereas most climate scientists say the world needs to curb fossil fuel emissions as fast as possible, Koonin is proposing a slower approach that focuses on adapting to the effects of climate change over addressing its root causes.

“We should be doing it in a graceful way and we should not be wrecking or severely impacting other aspects of society as we do that,” Koonin said of the transition to renewable energy. “Most people think we should be running the whole country on wind and solar. Well, in fact, that’s practically impossible because either it would cost a zillion dollars or it would be terribly unreliable or both.”

Kirtman says Koonin is right that there is always uncertainty in any scientific field. What Koonin fails to acknowledge, though, is that while there are still aspects of climate science that aren’t certain, many are.

“That we’re seeing more Category 4 and 5 [hurricanes] is certain. The fact that the climate system is warming is certain. The fact that it’s due to human activity is certain. The fact that sea level rise is responding, in terms of thermal expansion and freshwater input, is certain,” Kirtman says. “Where we start to get into vagaries is in some of the local (and) regional impacts.”

Everything we know about climate change makes it clear that the status quo of energy production is unsustainable, according to Denning from CSU, which means climate action needs to be more aggressive to stave off the worst impacts.

“If we just keep burning coal, oil and gas to run modern society for the rest of the century, that’s in the neighborhood of as much heat as was added at the end of the last ice age,” he said. “It took 100 centuries for that. We could do it in one century. That’s a bad idea.”

As Kirtman puts it, “the cost of inaction far outweighs the cost of action.”

Credit: U.S. Government, public domain via Wikimedia Commons

‘A brilliant theoretical physicist,’ but not a climate scientist

Koonin is the founder of NYU’s Center for Urban Science and Progress, which explores how data and technology can be used to solve complex urban problems. He served as Undersecretary for Science in the U.S. Department of Energy under President Barack Obama from 2009 to 2011 and for five years was Chief Scientist for the oil and gas company BP.

Marianne Lavelle, an Inside Climate News reporter who has covered Koonin and his book, says Koonin’s views on climate change were developed during his time at BP.

“Obama’s chief Energy Secretary Steven Chu brought him aboard because he was contrarian and, really to his credit, wanted to hear from all sorts of views,” said Lavelle, who interviewed Chu as she was reporting on Koonin’s book.

When the IPCC issued its fifth assessment report in 2013, two years after Koonin left his position in the Obama administration, the American Physical Society decided to review and update its 2007 Statement on Climate Change, which affirmed human-caused climate change and the seriousness of its consequences. Koonin, a member at the time, led the committee behind that process.

“Professor Koonin instituted this adversarial red team-blue team approach to assessing the scientific evidence for human effects on climate,” said Benjamin Santer, who at the time was a climate researcher at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and was asked to be a member of the blue team.

In January of 2014, Koonin held his red team vs. blue team exercise at NYU, giving the three-member teams 30 minutes each to present, followed by a Q&A session with the committee. “In the end, the red team did not convince the members of this committee that warming was not happening and that humans were not responsible for changes in climate. The red team lost,” says Santer.

Following that exercise, Koonin proposed a revision of the society’s climate statement that the committee rejected. Koonin then resigned.

“The review continued, adhering to the standard process, and resulted in the 2015 Statement on Earth’s Changing Climate,” which affirmed the reality and seriousness of climate change, an APS spokesperson wrote in an email to ADAPT.

Last year, the Lawrence Livermore National Lab invited Koonin to give a virtual lecture about his book, similar to the Tuesday event hosted by the World Affairs Council of Jacksonville. “When news of Professor Koonin’s lecture became public at the lab, many of my younger colleagues in the climate program were horrified. As one of them noted, it felt like they were ‘invisible’ and as if all the work that we did did not matter, that what was really important was showing favor to a powerful and influential individual who was on Livermore’s Board of Governors, but was not knowledgeable about the science of climate change,” says Santer.

Santer reached out to the director of the lab detailing his own personal history with Professor Koonin and asking for equal time on stage to address what he saw as “myths and misconceptions” that Koonin was propagating. Santer did not ask for the event to be canceled. Santer describes the response he received from the director as “dismissive,” so he decided to retire early.

“I had always intended to continue being involved with Livermore as a visiting scientist or in some sort of visiting capacity until the Koonin episode, at which point I completely cut all ties with Lawrence Livermore National Lab,” Santer says. His last day working at the lab was Sept. 30, 2021.

“Professor Koonin is a brilliant theoretical physicist, but he’s not a climate scientist and there are no quick shortcuts to scientific understanding. You can’t magically assimilate understanding of computer models of the climate system,” Santer said.

This sums up much of the criticism leveled against Koonin: he is out of his depth when he’s talking about climate science.

“Dr. Koonin is a physicist who has never been involved in climate science nor has he published a single climate-related paper in the peer-reviewed literature,” Susan Joy Hassol, a prominent climate communicator, director of Climate Communication and a contributing author of the IPCC’s sixth assessment report released in 2021, wrote in an email to ADAPT. “If you have a heart problem, you go to a cardiologist, not a dentist. Presenting Dr. Koonin as a climate change expert is like a dentist practicing cardiology.”

Kirtman from the University of Miami agrees with that assessment, but he thinks Koonin does make some valid points.

“I would argue that he probably isn’t on firm ground arguing about the climate science itself. But how it’s portrayed in the media and how politicians use it to pursue the policy objectives that they want to pursue, I’m sure he’s on firmer ground there, intellectually,” Kirtman says. “Do I think that it’s been sensationalized by some in the media? Yes. Do I think it’s been sensationalized by some reporters? Yes. But also, I think if you take a balanced view and all the information that we have, we are facing a serious existential threat.”

Koonin, in no uncertain terms, says he disagrees with that framing. “From a public relations point of view, I’d like to cancel the ‘climate crisis.’ I’d like the administration and some leading scientific organizations to stand up and say, ‘There is no crisis, but we acknowledge that there is a problem here to be dealt with, along with many of the other problems that we’ve got facing us,’” Koonin said.