The vast majority of the more than 1.7 million households in Florida that have flood insurance policies through the National Flood Insurance Program will likely see their rates rise as Congress faces a Sept. 30 deadline to reauthorize the program that’s drowning in debt.

The NFIP owes more than $20 billion, money it’s had to borrow, for the most part, over the past 15 years amid intensifying floods and a proliferation of coastal development that’s simultaneously exposed more properties to that flooding.

Now the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), which administers the NFIP, has a plan to stabilize the program: a new rating system called Risk Rating 2.0: Equity in Action.

Credit: John Raoux, AP Photo

Risk Rating 2.0

Risk Rating 2.0 is the first change to the way the NFIP calculates premiums since the 1970s and represents the biggest shift since the program was founded in the 1960s. FEMA plans to introduce it on Oct. 1 of this year.

Under the current system, flood zones are used to calculate a property’s flood insurance premium. Under Risk Rating 2.0, premiums will be tied to “the specific features of an individual property.”

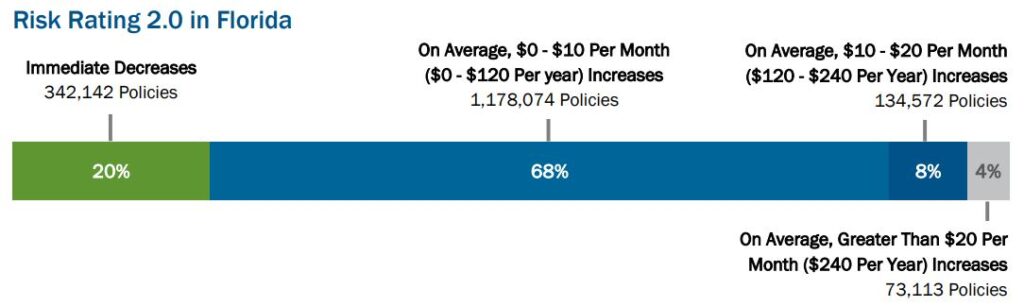

Today, policyholders see an average premium increase of about $8 a month. Under Risk Rating 2.0, 80% of policyholders in Florida will see their premiums increase, with the vast majority of those increases $20 or less per month ($240 per year or less). The remaining 20% will see their premiums decrease. For policyholders whose premiums will be going up, annual increases will be capped at 18%.

“The new pricing methodology is the right thing to do. It mitigates risk, delivers equitable rates and advances the Agency’s goal to reduce suffering after flooding disasters,” wrote David Maurstad, senior executive of the NFIP, in FEMA’s announcement of Risk Rating 2.0 this April. “Equity in Action is the generational change we need to spur action now in the face of changing climate conditions, build individual and community resilience and deliver on the Biden Administration’s priority of providing equitable programs for all.”

Starting Oct. 1, new policies will be subject to the new rating methods, and existing policyholders who are eligible for renewal will immediately be able to take advantage of decreases in their premiums. Premium increases for others won’t kick in until April 1, 2022.

Given that many policyholders will see their premiums increase, it’s no surprise that many oppose the change. A City Council in Texas recently unanimously approved a resolution opposing the new rating system, and politicians like Republican Congressman Steve Scalise from Louisiana are speaking out against it as their constituents complain about rate increases. But FEMA and others say the changes are necessary if the NFIP is going to survive.

Credit: AP Photo

Inception

During the first five months of 1927, the U.S. was hit by five storms, each of them bigger than any single storm in the previous ten years. Eventually deluge after deluge became too much to bear, levees burst, and the swollen Mississippi River flooded some 27,000 square miles of land across seven states from Illinois down to Louisiana.

“Once more war is on between the mighty old dragon that is the Mississippi River and his ancient enemy, man,” read The New York Times on May 1, 1927.

As a result, between 250 and 1,000 people died, more than 600,000 people were left homeless (most of them racial or ethnic minorities) and property losses topped $1 billion (which at the time was about a third of the federal budget), making the Great Flood of 1927, as it came to be called, one of the costliest disasters in U.S. history.

Flood insurance had been offered by private insurers since 1895, but many of them fled the marketplace after the Great Flood, just as the country was about to enter the Great Depression.

After several failed attempts to create a national system of flood insurance, Congress eventually passed the Southeast Hurricane Disaster Relief Act in 1965 after Hurricane Betsy inundated New Orleans. A resulting federal report stressed a dual purpose for flood insurance: 1) Offer financial relief and 2) Regulate land use and development in floodplains.

The report sounded optimistic that a flood insurance program could succeed, but also included a warning: “For the Federal Government to subsidize low premium disaster insurance or provide insurance in which premiums are not proportionate to risk would be to invite economic development in floodplain areas. Further, insurance coverage is necessarily restricted to tangible property; no matter how great a subsidy might be made, it could never be sufficient to offset the tragic personal consequences which would follow enticement of the population into hazard areas.”

Two years later, the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 created the NFIP.

Credit: Sky Cinema

A warning unheeded

Since then, local planning authorities and land-use regulators have largely been unable, or unwilling, to prioritize flood mitigation over development, despite several features in the National Flood Insurance Program meant to encourage them to do so.

“Local communities, especially on the coast, which is my specialty, have economic incentives to develop anywhere, including in a floodplain,” said Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Gilbert Gaul, author of The Geography of Risk: Epic Storms, Rising Seas, and the Cost of America’s Coasts. “They want to build their tax bases, they want to build their communities, they want to build their towns, they want to sell them houses and get tax revenues.”

In New Jersey, for example, Republican Gov. Tom Kean tried to restrict coastal land development in the 1980s, but his efforts were stymied by major lobbying efforts led by home builders. In 1994, the state passed a law allowing washed-out properties to be rebuilt in the same spot. In 2012 Hurricane Sandy destroyed about 346,000 homes and caused billions of dollars worth of damage in New Jersey alone.

“People opposed every one of our measures because short-sighted people say ‘Let’s enjoy it today, don’t worry about tomorrow,’” Kean told The Huffington Post.

This pattern has repeated itself time and time again across the country, supporting one of the program’s main criticisms: that federal disaster-relief programs don’t actually promote risk averse behavior, as many hoped the NFIP would. Rather, they incentivize people to take risks they otherwise wouldn’t — like living on a flood-prone coastline — and reward them when their luck inevitably runs out.

In the case of the NFIP, this plays out in two ways:

- Subsidies: The premium rates for most NFIP policies are supposed to reflect the true flood risk, but Congress has required FEMA to subsidize flood insurance for properties built before their community’s first flood insurance rate map was produced. FEMA also grandfathers in properties at their rate from past rate maps.

- “Severe repetitive loss” properties: These are properties that have received four or more NFIP claim payments of $5,000 or more, or two claims with a cumulative total that exceeds the value of the property. While SRL properties make up just 0.6% of the more than 5 million properties insured through the NFIP, they receive a disproportionate 9.6% of all damages paid out through the program, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Credit: U.S. Navy via Wikimedia Commons

Insolvency

Despite all of the issues plaguing the NFIP, the program was pretty much able to sustain itself for decades with the premiums it collected and the occasional loan from the U.S. Treasury. It wasn’t until Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005 that the program started to become insolvent.

In the aftermath of Katrina, the NFIP found itself $18 billion in debt. To meet its obligations, the program’s borrowing authority had to be increased from $1.5 billion to nearly $21 billion. After Hurricane Sandy less than a decade later, Congress had to increase the NFIP’s borrowing authority yet again, this time to more than $30 billion. In October of 2017, Congress cancelled $16 billion of NFIP debt so the program could pay claims for Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria.

The NFIP now owes more than $20.5 billion to the U.S. Treasury and is paying more than $1 million in interest every day. FEMA predicts that over the next 10 years the NFIP will have to pay $5.7 billion in interest expenses. By 2029, it’s expected that the program will have paid about $10.3 billion in total interest.

“Whether or not FEMA will ultimately be able to pay off the debt is largely dependent on future insurance claims, namely if a catastrophic flooding incident such as Harvey, Sandy, or Katrina occurs again and with what frequency,” reads a recent document from the Congressional Research Service.

Credit: NOAA via Wikimedia Commons

What changed?

The NFIP should have helped deter development in flood-prone areas, ensured that any new development in a floodplain would be designed to minimize flood damage risk and decreased how much the federal government spent on disaster recovery costs — but, for one thing, storms and floods are worse today. This month’s report from the U.N. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change makes it clear that catastrophic flooding events are becoming more common as climate change continues to accelerate due to human activity.

“The NFIP is predicated on the assumption that flood risks are static and change little over time,” reads a commentary from Columbia Law School and the NRDC. “Climate change is proving that assumption to be extremely dangerous and costly.”

According to the IPCC report, climate change is causing more extreme weather, like heavy downpours and catastrophic hurricanes, which leads to more frequent and intense floods. A FEMA-sponsored study estimates that the size of the nation’s “special flood hazard areas” — areas with a 1% or greater chance of flooding in a given year — will grow by 40% to 45% and the total number of NFIP policies will double due to both climate change and population growth by the end of the century. If that scenario plays out, the average amount the NFIP would have to pay to cover claims could increase by as much as 90% and the average premium would have to rise by about 70% in today’s U.S. dollars to offset the anticipated increase.

Sea level rise will also exacerbate the problem of severe repetitive loss properties. The NFIP paid an estimated $5.5 billion to repair and rebuild more than 30,000 SRL properties between 1978 and 2015. The NRDC estimates that 3 feet of sea level rise by 2100 — a middle-of-the-road projection — could burden the NFIP with another 820,000 SRL properties. Six feet of sea level rise, closer to a worst case scenario, could add more than 2.5 million SRL properties. If those scenarios play out, the NFIP would likely have to pay between $143 billion and $447 billion in flood insurance claims to repeatedly rebuild these homes in coastal areas.

Credit: U.S. Department of Energy via Wikimedia Commons

How did we get here?

In July 2012, just three months before Hurricane Sandy struck the Eastern Seaboard, Congress passed the Biggert-Waters Flood Insurance Reform Act, which attempted to fix some of the problems plaguing the NFIP. The legislation required the NFIP to produce updated floodplain maps, improve local building-code enforcement, ax insurance subsidies for certain properties and move toward charging premiums that more accurately reflect a calculated flood risk, among other reforms.

Louisiana Sen. Mary Landreiu, a Democrat, fought against the legislation, urging her colleagues to consider the affordability of insurance premiums. The next year, home-building and real estate industry spokespeople showed up at congressional hearings, warning that Landreiu’s fears were coming true. Even Democratic Congresswoman Maxine Waters of California, the co-sponsor and namesake of the law, said she would never have drafted the law had she foreseen the impact it would have on rates.

“Never in our wildest dreams did we think the premium increases would be what they appear to be today,” Rep. Waters was quoted as saying in The New York Times after the law passed.

Still, a 2013 study from the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that only about 8% of policyholders saw immediate rate increases, and many of those were some of the most heavily subsidized policies. But the slowness of settling flood claims after Hurricane Sandy gave vocal policyholders fresh ammunition. In March 2014, Congress passed the Menendez-Grimm Homeowner Insurance Affordability Act, which rolled back many of the strongest provisions in the reform act of 2012.

Despite all of the NFIP’s issues, policyholders in Florida view it as an essential. Ellen, who asked ADAPT not to use her last name, lives in Jacksonville’s Mandarin area, down the street from Deep Bottom Creek and a few blocks from the St. Johns River. She’s required to have flood insurance.

Ellen and her husband have watched their annual premium slowly rise over 20 years to just over $1,000. They never had to file a claim until Hurricane Irma struck in 2017.

“In Hurricane Irma, our homeowners insurance didn’t cover anything because the damage was all water, so we worked exclusively with the flood insurance,” she said. An appraiser estimated that the home suffered $100,000 to $150,000, and it was all covered by the NFIP. The only expense that wasn’t covered was a place to live while the home was restored.

The couple are now working to upgrade their home so that it will be protected if the area gets flooded again, which she thinks is inevitable. “It’s very important,” she said of the NFIP. “But it was designed for a world that we don’t live in anymore. We need something different.”

Journalist Gilbert Gaul believes that Risk Rating 2.0 could help fix some of the problems that have been plaguing the program, the main form of flood protection for millions of Americans, but he worries that politics will get in the way again.

“There are countless examples of when FEMA… has tried to do the right thing. Then Congress gets involved,” he said. “It’s usually coastal lawmakers — they step in and they stop FEMA from doing what it’s supposed to do.”

FEMA did not respond to a request for comment by this story’s deadline.