Even in the age of smartphones, it’s still a daily routine for millions of Americans: breakfast, a cup of coffee and the morning weather report from their favorite TV weathercaster.

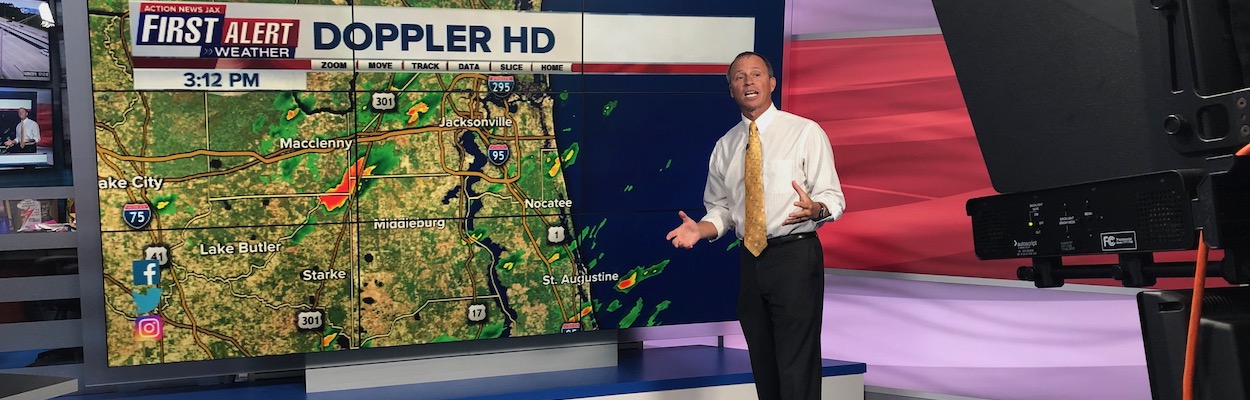

As recently as 2015, FiveThirtyEight found that about 20% of Americans still got their weather forecasts from local TV news. And when it comes to local news that affects their daily lives, Americans rank weather, by far, the most important topic that keeps them tuned in.

Credit: Pew Research Center

That’s why local weathercasters — who are increasingly having to communicate potentially lifesaving information to their audience as climate change contributes to more extreme weather — are well positioned to help educate the public on climate change, which researchers say is necessary before people can buy in to addressing its causes.

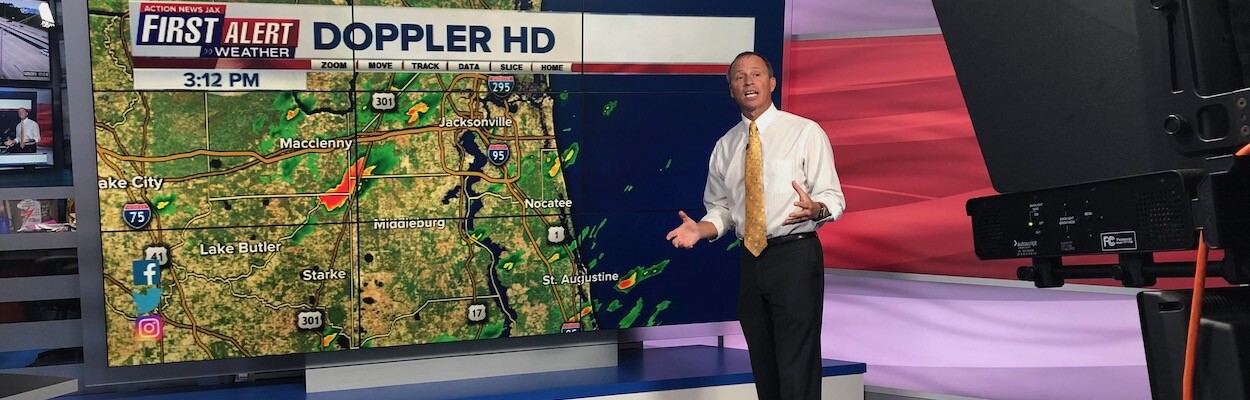

Mike Buresh is chief meteorologist at Jacksonville’s CBS and FOX affiliate, Action News Jax. He’s been working in Jacksonville for nearly two decades, and his TV weathercasts reach close to 100,000 people every day.

Buresh and nearly all of his fellow weathercasters agree that climate change is happening, but that hasn’t always been the case. Just nine years ago, in 2011, less than 1-in-5 TV weathercasters in the U.S. said they thought human activity was driving climate change. Fast forward to 2017: 95% of weathercasters thought climate change is happening and 70% thought human activity plays a role.

That shift helps explain why on-air reporting about climate change by TV weathercasters shot up by about 3,200% between 2012 and 2018.

As Action News Jax’s resident scientist, Buresh believes it’s “critically important” to talk about anything science-related, including climate change, which he talks about on air about five times a month. But, he said, it’s a challenge to fit those conversations into his regular weathercasts due to time constraints.

“This time of year, I’ve got two minutes to present hurricanes, thunderstorms, the weekend and what’s going to happen for you tomorrow,” he said.

He has more opportunities to discuss climate change in his blog and in 30-second vignettes he regularly produces for TV.

Another factor driving the increase in local coverage of climate change might be a program called Climate Matters, which started in 2010. Climate Matters, from the nonprofit Climate Central, offers weathercasters and other journalists free reporting resources, easy-to-understand text and visuals that they can use to report on local climate impacts and solutions, like this recent package on fall warming.

Today, more than 1,600 weathercasters and journalists across the country receive Climate Matters materials, with more than 100 of them in Florida and 11 in the Jacksonville area, including Buresh.

Buresh uses Climate Matters materials two or three times a month, like in this “Buresh Blog” post. He said Climate Matters gives him access to data and materials he likely wouldn’t have time to put together on his own.

Climate Matters began as a pilot project with one TV meteorologist in Columbia, S.C.: Jim Gandy at WLTX. After Gandy ran 13 two-minute climate-related stories over the course of a year, a followup evaluation found that viewers had developed a more science-based understanding of climate change.

Since then, a more thorough study of two meteorologists using Climate Matters materials, John Morales at WTVJ in Miami and Tammie Sousa who was then at WMAQ in Chicago, found that “offering climate information via trusted communicators in local media is an effective approach to increasing acceptance of, concern about and engagement with climate change.”

But what makes weathermen and women “trusted communicators” on a polarizing topic like climate change?

Bernadette Woods Placky, a former Emmy-winning meteorologist who is now the director of Climate Matters, said, “Friends and family are highly trusted, but sometimes they don’t really know the fundamentals of climate science or what it’s doing to different communities. Climate scientists are very well trusted, as they should be, which is great. But a lot of the public doesn’t have access to a climate scientist, especially on a regular basis.”

Enter TV weathercasters.

“They really see how weather is changing, both in the extremes and the everyday, and they have the ability to connect it with the forecast in that ongoing conversation with their public,” Placky said.

A 2012 study by Yale and George Mason universities found that 74% of Americans trusted climate scientists, and 62% trusted TV weathercasters as sources of information about climate change. Meanwhile, 43% said they trusted the “mainstream news media.”

Research has also shown that across the political spectrum, watching climate videos similarly increased viewers’ acceptance of climate science and concern about climate change.

“I think one of the advantages of weathercasters is they’re not really seen as polarized. They’re seen as a kind of content expert,” said Irina Feygina, lead author of the Climate Matters study and previously the director of behavioral science and assessment at Climate Central.

But that’s not to say weathercasters don’t face any pushback when they tell stories about climate change. One Jacksonville-area TV weather forecaster, who declined to be identified, said whenever the station publishes anything about climate change on its website, a wave of negative feedback floods in.

It’s a fear among many journalists, formed from experience.

But, according to Placky, public opinion is shifting.

“When we first started the program, I would say there was a lot more pushback, and there was a lot more fear of pushback,” she said. “Some of our members, or the people who are in our network, have found that they had more fear of getting pushback from their management or the public than they actually got in reality.”

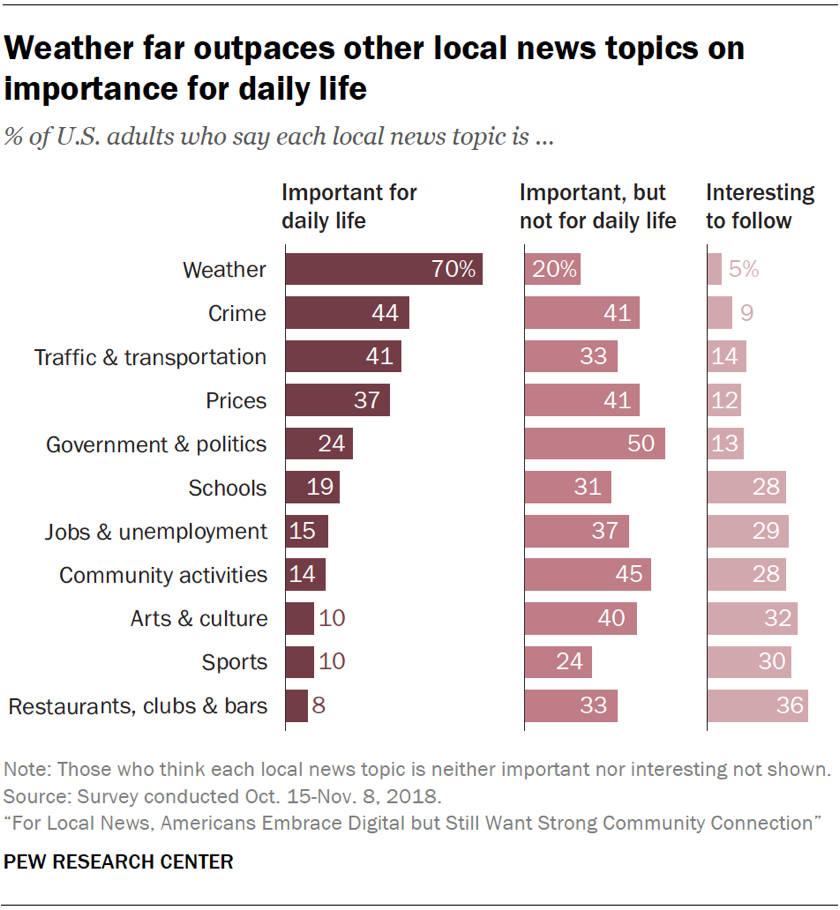

And the numbers bear that out. An April survey by Yale and George Mason universities found that Americans’ understanding that climate change is happening has tied the prior all-time high, even as the COVID-19 pandemic understandably continues to dominate people’s attention. Americans who think global warming is happening now outnumber those who don’t by about 7-to-1, and acceptance in Florida is even higher, according to Florida Atlantic University.

While he never gets pushback from station management when he talks about climate change, Buresh said he does get regular pushback from viewers and readers, mostly on social media. But, he said, that’s part of the job.

“I get feedback everyday, whether it’s about something I said, wore, predicted, where my hair was, how long my nose is, how tan I am, how much I move on camera. Man, take your pick,” he said. “It gets bitter and weird and strange and I can’t wait ‘til I retire because that account will be deleted as soon as I can do it.”

But he said fear of negative feedback shouldn’t stop weathercasters from presenting facts to their audience.

Placky said those who do can take heart in knowing that, given the proven effectiveness of weathercasters and meteorologists as climate communicators, they are playing a critical role in the growing acceptance of climate science among Americans, a trend that she said needs to continue.

“We’ve come a long way, but we really still have a long way to go because if we truly want to stabilize our climate, this isn’t about just getting a couple of pieces of legislation passed or public understanding to a certain level,” she said. “We’re going to need decades of sustained conversation for people to understand what’s really going on around them and what they can do.”