In September of 2017, flooding caused by Hurricane Irma destroyed the house that Tom Davitt was renting on Jacksonville’s Westside and wrecked tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of his uninsured possessions.

“I rolled out of bed because I thought it was my alarm, and it was a tornado warning. And I stepped into a foot and a half of water,” the 56-year-old yacht broker said in February. “I’m basically starting all over at my age.”

Tom Davitt at Sadler Point Marina in Jacksonville. Credit: Brendan Rivers/WJCT News

A long-time Northeast Florida resident, Davitt had lived through wild weather and disasters before, like the time an unnamed storm dropped an oak branch into his living room. A gale also destroyed 300 feet of his dock in 2009, and a follow-up squall stole the rest.

“Is it going to happen again?” Davitt said. “Lord, I hope not. I don’t want another one of those 50-year storms for Jacksonville. I don’t think it’s going to be 50 years before it happens again.”

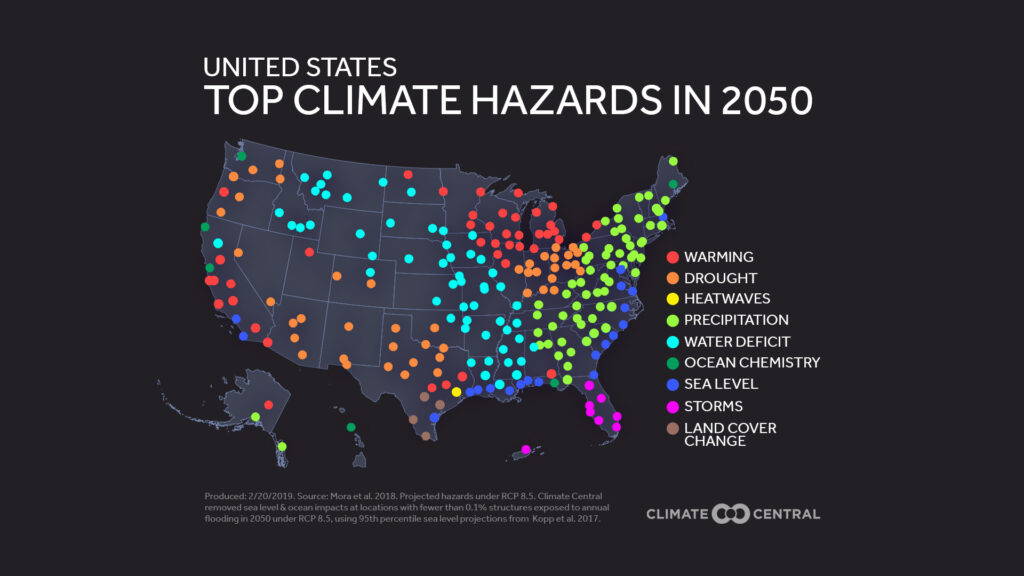

According to research published last November in the journal Nature Climate Change, pollution is raising global temperatures, which escalates hazards in Jacksonville posed simultaneously by droughts, heat waves, storms and heavy rainfall – all as sea levels rise.

“This is what makes the prospect of climate change so scary,” said Camilo Mora, a geographer and associate professor at the University of Hawaii, Manoa, who led the study.

Mora and 23 fellow researchers analyzed how human systems are going to grow more vulnerable to these disasters.

They reviewed more than 12,000 scientific papers, identifying 467 ways that health, food, water, infrastructure, the economy and security are affected by the climate under normal circumstances. From their analysis emerged a geographical index that combined past data with projections to show how climate change will make the hazards even worse.

The increased risks come as Jacksonville sits almost a foot lower in the sea than it did a century ago, which has increased coastal flooding. Roughly $870 million worth of homes are projected to be at risk of regular flooding in Duval County alone by 2050.

“How do you adapt to a hurricane now?” Mora said. “What about heat waves? What about saltwater intrusion? When you look at all of these cumulatively – all of these hazards together – it’s going to be like an attack.”

Severe drought, heatwaves and wildfires have already taken place over the past few decades, hurting the state’s agriculture sector. A 2006-2008 drought cost Florida roughly $100 million per month, and 1998 wildfires destroyed upwards of 300 properties and caused hundreds of thousands to evacuate.

The prospect of more suffering and economic pain caused by worsening storms, wildfires and heat waves has been spurring some Americans to fight to reduce greenhouse gas pollution, which is causing global temperatures to rise and fueling a push by prominent Democrats for a “Green New Deal” to urgently reduce emissions.

To slow the effects of climate warming, some cities, states and nations have been taking steps to curtail the use of fossil fuels and promote cleaner alternatives. But even if every country lived up to its commitments under the Paris climate agreement, temperatures are projected to increase well beyond the goals of that 2016 pact. That’s prompting a growing number of political leaders to back the kind of large-scale mobilization of clean energy that’s imagined under the Green New Deal resolution sponsored by dozens of Democrats. As a far-reaching and wide ranging “10 year-national mobilization” to address both economic inequality and climate change, the Green New Deal also contains many broad objectives that have little to do with the climate. But its proposal to meet 100% of U.S. power demands through renewable, zero-emission sources and to remove pollution and greenhouse gas emissions from manufacturing “as much as is technologically feasible” are among the most ambitious climate-related goals being put forth in Congress. Most of the initial plans from Democrats running for president have not gone as far, or as fast.

Climate scientists have mapped out four main future scenarios that humanity might follow, depending on the extent to which we slow the release of greenhouse gas pollution. RCP 2.6 is considered the “best-case” scenario of these, where the world stops releasing carbon pollution by 2070. On the flip side sits RCP 8.5, where only limited efforts are made to reduce emissions in the atmosphere, frequently dubbed the “worst-case” scenario.

Research shows that even the best-case scenario would mean worse storms, floods and heat waves for Jacksonville. And it shows unchecked pollution will bring worse and more frequent disasters, sometimes striking at the same time.

But even disaster-weary locals like Davitt eye the dialogue surrounding emissions and climate change warily.

“The global stuff? God, I don’t know,” he said. “I hear, you know, the pros and cons of this and that, and if the ice is doing this, then there’s more ice this year. And I honestly don’t know which way it’s going.”

Davitt is still on the fence when it comes to investing in preventing and lessening the effects of climate change. At the same time, he doesn’t rule out supporting far-reaching climate protections like the Green New Deal.

“I know the cars and the pollution and, you know, it’s got to do something to the climate,” Davitt said. “If people were more cognizant about what’s going on, we wouldn’t have a lot of this stuff, I don’t think.”

The Green New Deal and International Action

Even if Americans embraced far-reaching climate action like the Green New Deal, the country’s actions alone would not be enough to keep global warming to the best-case scenario.

“The real question is kind of a dynamic one: How would the Green New Deal change the ability of other nations around the world to contribute?” said Michael Wara, an environmental lawyer and climate policy expert at Stanford University. “We need to inspire others with leadership. And we also need to develop the tools that other people can pick up and use to reduce their own emissions.”

Wara said the Green New Deal proposal should be viewed cautiously. While the concept promises aggressive action, the details aren’t available for analysis beyond speculation.

“We need to be looking at what the details are, because the details in this sort of thing matter,” he added.

Back in Jacksonville, Todd Sack, a gastroenterologist, says he’s fully behind the push in Congress for far-reaching climate action.

“We should all support the concept of the Green New Deal,” said Sack, who served on the city’s Environmental Protection Board for eight years and chaired the Florida Medical Association’s environment and health initiative. “It’s about plotting a transition to a carbon-free world, which we can do by 2030 if we push it.”

Sack’s patients’ health is threatened by rising temperatures.

“Climate change means flooding events. It means heat events where thousands of people could die from the extreme heat days. It means vector-borne illnesses, it means mental illness,” he said. “As a city, we need to begin to prepare our community for these 30- to 50-year eventualities.”

The Green New Deal faces stiff political opposition, including from many Florida lawmakers, who say they’re opposed to many of the policy proposals laid out in the legislation introduced by Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY) and Sen. Ed Markey (D-Mass).

“It is unilateral disarmament, economically,” said Sen. Marco Rubio, R-FL, during a recent interview on FOX News. “It’s actually self-inflicted damage that we would do to ourselves if even pieces of that were implemented.”

Congressman John Rutherford, R-FL4, who represents much of Jacksonville, described the Green New Deal as a “socialist manifesto masquerading as an environmental proposal.”

He does, however, support some aspects of the resolution, specifically the call to build up resiliency.

“In fact, I just recently joined the American Flood Coalition,” Rutherford said. He also pointed to his collaboration with former St. Augustine Mayor Nancy Shaver to request federal funding for a study on sea level rise and flooding.

While he supports efforts to defend against rising seas and flooding, Rutherford said he’s not sure what the causes are.

“I agree that climate change is happening, and we certainly have sea level rise,” he said. “I question what part of that is man made and what part of that is natural phenomenon.”

That’s as scientists have concluded, besides atmospheric pollution, “there are no credible alternative human or natural explanations” for global warming during the past century, according to a federal assessment published last year.

Rutherford said he’s not opposed to the goal of transitioning the U.S. to 100% renewable energy, but he doesn’t believe it’s possible to get there in the next decade – as the Green New Deal calls for – and he doesn’t agree with the economic policies Ocasio-Cortez and Markey are suggesting.

“I think the free market solutions and innovations will come along,” he said. “That is how this change should take place.”

“We’ve already pretty extensively reduced our use of coal,” he said. “We are relying more and more heavily on the gases. So I think that transition and innovation is taking place as we speak.”

Grappling Locally With a Global Problem

Despite that prevailing attitude from Florida’s elected officials, environmental watchdogs like St. Johns Riverkeeper Lisa Rinaman continue to call for ambitious climate policy action.

“We need to have a combination of local, state and federal policies because the crisis is much bigger than one community,” she said. “We have to act locally and engage globally.”

In her city, efforts by Jacksonville’s leaders are focused on adaptation and preparation rather than reducing pollution. The newly formed Storm Resiliency and Infrastructure Development Review Committee and Adaptation Action Area Working Group are aimed at improving citywide flood resiliency.

“This is something that we as Floridians can’t run from,” Rinaman said. “We have to make sure that we’re addressing it head on and do our part to be more resilient now.”

Jessica Hellmann, director of the Institute on the Environment at the University of Minnesota, who wasn’t involved with the study, agrees.

“The more we think about these hazards being layered on top of one another, the more I think that this really emphasizes the importance of local resilience and building up the local capacity for communities to take care of themselves,” she said.

“It’s about neighborhood-level preparation for emergency plans for evacuation — not just relying on what the state or the country says needs to be done,” Hellman said.

A civic, grassroots approach like this – to help manage the onslaught of climate disasters – is strongly supported by Davitt, the Jacksonville yacht broker.

“I know there’s other issues all over the world, and bad issues,” he said. “I’m more concerned about Jacksonville and where I live.”

Copyright 2019 ADAPT