Starting with the arrival of the first immigrants in the 1890s, Arab Americans have had a major impact on the growth and development of Jacksonville. Many early immigrants lived and operated businesses in LaVilla. Here’s a look at five sites in LaVilla with connections to Jacksonville’s vibrant Arab American community.

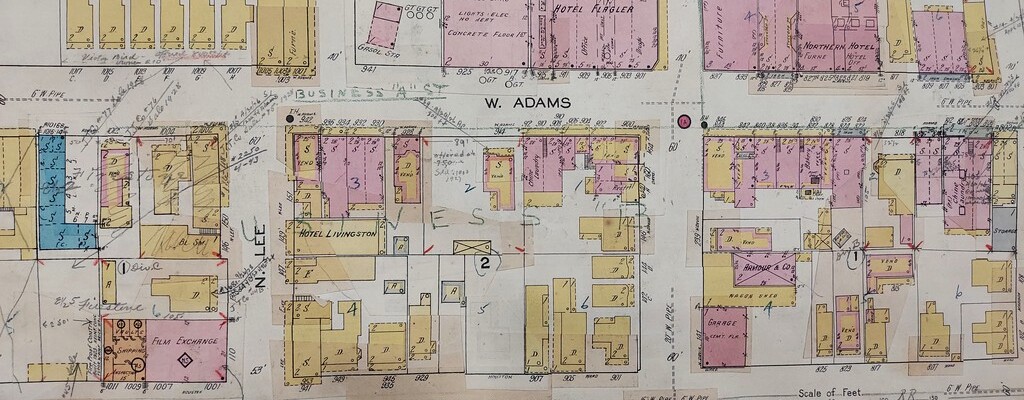

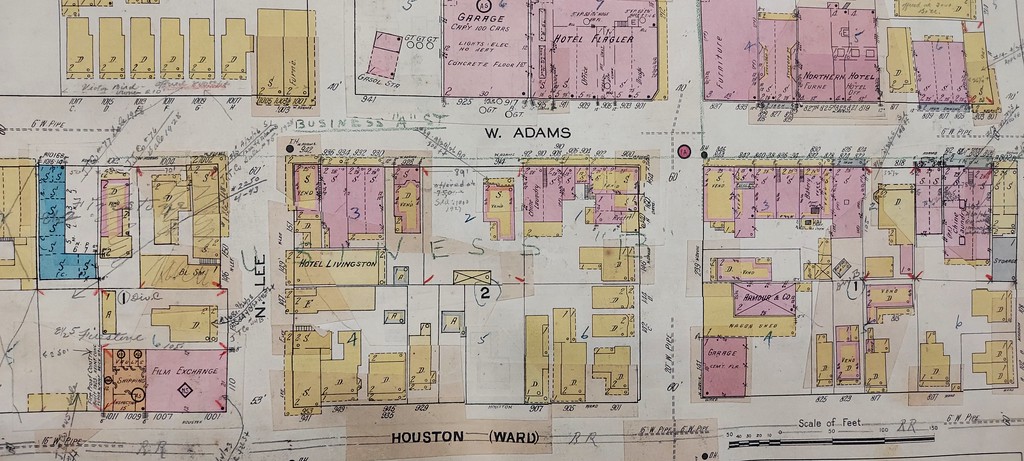

Arab Americans have a long history in Jacksonville tracing back to the 19th century. Between 1890 and 1920, hundreds of immigrants arrived and settled in Jacksonville from an area of the Middle East that is now home to the countries of Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, and other territories. By 1910, 75% of Jacksonville’s early Arab American immigrants resided in the city’s 7th Ward ( now known as LaVilla) and 8th Ward (west of Downtown) or nearby.

Early settlers there established themselves as grocers, peddlers and small businesspeople, and eventually they dispersed throughout the city over the course of the 20th century. Today, Jacksonville is home to the 10-largest Arab American community in the U.S.

From business to politics to the food scene, Arab Americans have made waves in every aspect of life in Jacksonville. However, the community’s early 20th century cultural contributions and sites associated with the historic LaVilla neighborhood are slowly being forgotten due to “urban renewal” and passage of time.

Here are five sites in LaVilla with connections to Jacksonville’s early Arab American community.

Greek & Syrian Club

The building at 618 W. Forsyth St. was built in 1910 with the Eagle Laundry Co. as its primary tenant. Generation X Jaxsons may remember it as an important part of the city’s music scene: During the 1990s, it was the home of the Milk Bar at Paradome. During the early 2000s, it became Club Kartouche, a nightclub known for Latin, rave, R&B, and hip-hop and featuring the likes of Ludacris and Trick Daddy during Super Bowl XXXIX. Unknown to most, the building also housed the Greek and Syrian Club that was established by A.K. Carazar in 1915. Despite being one of the last surviving buildings in LaVilla directly associated with the neighborhood’s Arab American and Greek immigrant communities, the building was demolished in 2020 for a gas station, convenience store and craft brewery.

Roosevelt Grill

Known for its greasy french fries, the Roosevelt Grill was a popular restaurant that catered to the crowds being entertained on West Ashley Street. Located at 808 W. Ashley St., the Roosevelt Grill was attached to the 1,150-seat Roosevelt Theatre. The building they shared was designed by Architect Roy Benjamin and included the Roosevelt Department Store. One of the first integrated restaurants in Jacksonville and frequented by the likes of Hank Aaron and Ray Charles, the Roosevelt Grill was owned and operated by Larry Hazouri and his brother Rufus “Pop” Hazouri — the grandfather of Jacksonville Mayor Donna Deegan — from the 1950s to the 1970s. Today, the site is the location of the LaVilla School of the Arts. While the Roosevelt Grill is no more, its spirit still lives on at Downtown’s oldest remaining restaurant, the Desert Rider Sandwich Shop on Hogan Street, still operated by Larry Hazouri.

Central Hotel

Erected at the northwest corner of Broad and West Beaver streets in 1912, the Central Hotel was designed by architect Mellen C. Greeley and built for the Ames Realty Co. Throughout its history, the building’s ground floor has been occupied by a variety of businesses that catered to the LaVilla community.

In one storefront, the Jacksonville Negro Welfare League provided counseling and referrals for African American veterans returning from World War II for employment, housing, education, and training benefits. The Negro Welfare League merged with a new Jacksonville branch of the National Urban League to create the Jacksonville Urban League in August 1947.

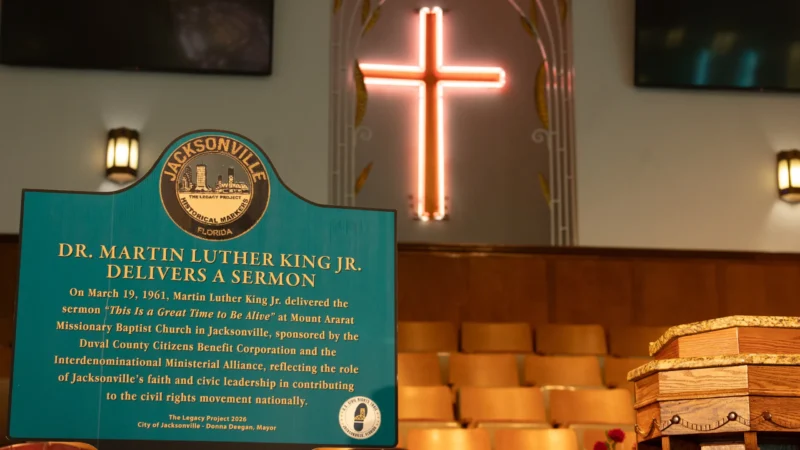

Another storefront was briefly leased to NAACP attorney Earl M. Johnson, Sr. during the 1960s. The first Black person to be elected to an at-large seat on the Jacksonville City Council, Johnson represented numerous civil rights activists during his tenure, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Rutledge Pearson, and the St. Augustine Four, who were fighting to desegregate public places in Florida.

The building’s ground floor retail space was anchored by the Vandoria Waldorf Cafeteria, a popular restaurant and bakery operated by hotel owners Julius and Vandora Jackson. However, between 1912 and the 1920s, this storefront was the location of a grocery market owned and operated by members of LaVilla’s Arab American community. Previous grocery market owners included Charles “Charley” Jacob Hazouri (1897-1969). Hazouri, a Lebanese immigrant, originally settled in LaVilla with his father, Jacob Nadir Hazouri — the great, great-grandfather of Jacksonville Mayor Donna Deegan — in 1904. Charley Hazouri went on to establish the Quality Fuel Oil Co. a few blocks northwest, near the present day S-Line Urban Greenway Trail at 1125 Wilcox St. The Central Hotel was designated as a local historic landmark in 1995.

Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing Park

In 2015, the Durkeeville Historical Society and city of Jacksonville collaborated to dedicate the birth site of two native sons, James Weldon Johnson and John Rosamond Johnson, as Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing Park. The park is named after the song written by the Johnson brothers, which has become known as the Black National Anthem. Expected to open this summer, the $4 million park lies on a block of land that silently includes a piece of history related to Jacksonville’s early Arab-American community.

While the Johnson family resided on the south side of the block, David Abdullah-Bey was their immediate nextdoor neighbor to the north, in the house fronting the southwest corner of Lee and West Adams streets. David Abdullah-Bey was born in Trupoli, Syria, in 1885. His father, Abdullah Abdullah Bey, was killed by a new regime in Syria during the late 1890s. Following his death, David and his siblings immigrated to the U.S. with their mother, Nijimie Hazouri Abdullah-Bey.

Arriving in Jacksonville in 1900 to be close to relatives, by 1906 he was living and working as a fruit retailer at 207 Bridge St. (now Broad Street) in LaVilla. Soon afterward, he moved next door to the Johnson family, where he also operated a grocery and meat market at 1102 W. Adams St. During the late 1920s, both the Johnson and Abdullah-Bey family properties were demolished and replaced with a Firestone Tire Co. warehouse and retail store. Abdullah-Bey then relocated to Miami where he was employed as a butcher at a retail meat market.

Khoury Brothers Dry Goods Building

The Khoury Brothers Dry Goods building is located at 827 W. Forsyth St.. Khoury Brothers was owned and operated by brothers William and Emmett Khoury for 45 years. Their parents, John and Catherine Khoury, immigrated to Jacksonville from Syria in the early 20th century. Constructed of brick, and built on the site of a former red light district bordello in 1953, the business primarily sold goods to firefighters, police officers and city officials. The business, which closed in the 1980s, offered a variety of dry goods, including winter coats and linens, at good prices. Stock was stored on the second floor of the two-story building. Today, it is one of a few surviving buildings associated with LaVilla’s early 20th century historic warehouse district, Railroad Row.