There’s a notion that has circulated in the Black community for generations: Black people have to be twice as good to get half as much.

From Barack Obama to Alvin Brown, Black people in positions of prominence and priority are forced to be nothing less than exceptional and excellent. So much so, that we’ve bought into our own hype, hash tagging our own social media posts with #blackexcellence. But excellence is tiring. It is burdensome. It sets an unrealistic expectation that in order to be Black we have to be beyond reproach. We’re not afforded opportunities after opposition, not given grace after grave mistakes, and not allowed missteps, stumbles, or falls. There is no room for error.

Our value, our worthiness, even our right to live, is tied up in our productivity. What we can do and how well we can do it. How we can serve and be an asset to others. This curation of our identity by what we can do or produce with our bodies, minds, and souls dates back to chattel slavery when an actual monetary valuation was assigned to Black bodies based on what could be produced by those bodies, minds, and souls. This is despite the fact that these Black people were forcefully kept ignorant and assumed to be soulless brutes because they called God by a different name.

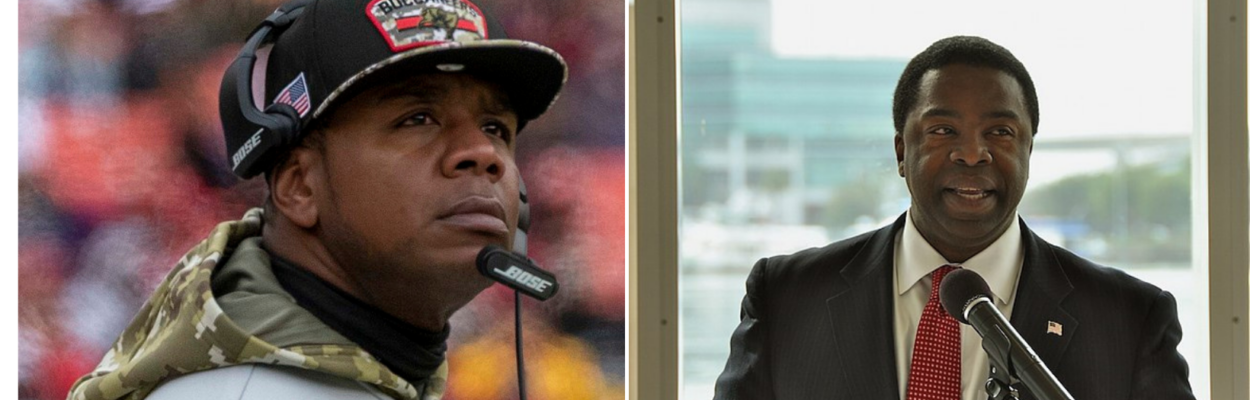

This valuation and need for validation has been unending. It is apparent in the pay gap. Black men make less than white men and white women. Black women make less than them all. The statistics are even more abysmal when including people who identify as Latin(x). But still we trudge on, playing corporate chutes and ladders whether we work in the NFL or work from home. That Doug Pederson was named Jaguars head coach just hours after Byron Leftwich withdrew his name from consideration is both uncanny and suspicious. It is no wonder that Brian Flores is suing the league for racial discrimination after being fired as the head coach of the Miami Dolphins.

Racism is pervasive in the league as it is in America. Second chances are often not given to Black coaching staff in the league just like in America. In America, we have to be right, be perfect, and be without error or failure as we are often sometimes the first. Bursting through glass ceilings unaware of the jagged pieces ready to cut us down with one wrong turn.

Our value, our worthiness in whatever we do in life is in question. It is in question in conversations about who should be the next justice of the Supreme Court, who should be admitted to college, and who children should learn about in history books. Our value is not inherent. Our worthiness is not implied. It must be proven. And even in proof it is second-guessed, questioned, and ultimately negated.

Also from Nikesha Elise Williams: An open letter to Gov. Ron DeSantis

It seems to me that we are never enough but always needed. It is not a compliment. To be called upon as the last option of last resort and still have to prove our value and worthiness for a seat at somebody else’s table is a slap in the face. By that same token, if we go off and build our own table, we are not funded or resourced at the same rate. But this is the game white supremacy forces us to play. And we play it—bootstrapping our way through without laces or boots—because we don’t want to be seen as less than or inferior. We have 400 years’ worth of proof to make up for even though we live in a country surrounded by 400 years’ worth of proof of what we’ve already done.

Is that not valuable?

Nikesha Elise Williams is an Emmy-winning TV producer, award-winning novelist (Beyond Bourbon Street and Four Women) and the host/producer of the Black & Published podcast. Her bylines include The Washington Post, ESSENCE, and Vox. She lives in Jacksonville with her family.