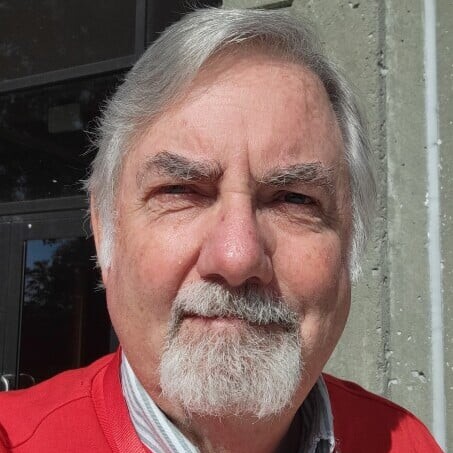

Artist Brenda Council delicately scrapes at the hand of a clay sculpture, then smooths the young boy’s wrist as the life-size image of his head seemingly looks over her work.

Behind the boy is a life-size bust of 19th-century abolitionist and author Harriet Beecher Stowe, who will join two boys — laborers in her orange grove — in a bronze statue to be unveiled late next summer at the Mandarin Museum and Historical Society’s facility at Walter Jones Historical Park in Mandarin.

The sculpture is taking shape now in the back of the 112-year-old Historic Mandarin Store & Post Office at 12471 Mandarin Road. As the likeness of Stowe, a former Mandarin resident famed for her 1851 anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, is formed in future weeks, visitors can watch Councill work on it from 10 am. to 2 p.m. each Friday through Sunday (except Christmas Eve and New Year’s Eve) through February.

Councill said it has been wonderful to interact with people who have visited as she sculpts. She said she envisioned its design showing Stowe interacting with the community she lived in, including “the underage children who sadly would have been employed in her orange groves.”

“These children would have been largely illiterate, and I am envisioning her walking through her groves and seeing these little boys who maybe have just gotten off their shift,” Council said as she smoothed more clay.

“She’s greeting them, and she asks them to sit down on an upturned orange crate, and she is going to read to them, and they are going to interact with little slates that they both have,” she said. “I just thought it was important to imply the idea that education of both black and white communities was very important to Mrs. Stowe.”

When the clay figures are done, they will be cast in bronze, the only life-size likeness of Stowe.

“It would not only enhance the landscape, but also pay tribute to a woman who was so monumental, so to speak, in U.S. and Mandarin history,” museum executive director Brittany Cohill said. “So many people don’t know that Stowe was in Mandarin and that she as an advocate right here for Florida, its tourism, its social uplift and education following the Civil War. … We are really excited.”

Stowe lived in a Mandarin Road cottage every winter from 1867 through 1884, wishing to be close to her son, Frederick, and his cotton farm across the St. Johns River in what is now Orange Park. She shared that home with her husband, the Rev. Calvin Stowe, who helped found the nearby Church of Our Saviour.

Stowe also helped the Freedmen’s Bureau found a school for African American children in Mandarin, purchasing the land and hiring the first teacher, in what is now the Mandarin Community Club. She and her daughters organized and acted in plays in the community, and she wrote of the area in her 1871 book Palmetto Leaves.

Up the road, the Mandarin Museum and Historical Society opened its facility in 2004 at the main entrance to the city’s Walter Jones Historical Park. The museum fronts part of a 10-acre farm started in 1873 by U.S. Army Maj. William Webb, then taken over in the early 1900s by Mandarin postmaster Walter Jones. Then in 1911, Jones opened his store and post office next to the community club, both across from Stowe’s long-gone winter home. The restored store, operated by the museum, is where Councill is creating her sculpture.

The Mandarin museum has a display on Stowe, including part of the decorative woodwork that once graced her Mandarin cottage. An oil painting of Stowe graces the main hall of the community club. But no full-size sculpture of her has ever been created, including at the Stowe Center in her home town of Hartford, Connecticut. So the museum and Councill came up with the “fantastic idea” to create the sculpture, which was approved by the city and Florida Communities Trust.

Councill, a Mandarin native, said it “was just a natural” for the sculpture to be in Mandarin.

“The Stowe Center has a sculpture, but it is not full size,” Councill said. “And having grown up in Mandarin, I felt like she deserved a greater legacy, and that legacy could be visualized in life-size sculpture. So I began planning this sculpture, always based in life size. And I also wanted the sculpture to be interactive.”

That means people who will visit the bronze sculpture at Walter Jones park can sit with Stowe on her bench and “visualize her legacy and have their picture taken with her” as a constant reminder of what she did when she lived there, Councill said.

The project also won the endorsement of Stowe biographer Joan Hedrick, who said “it is entirely fitting that such a monument be placed” in Mandarin.

“It will celebrate one of America’s most prolific and influential writers … [and] commemorate Stowe’s profound love of Florida,” she wrote in a news release. “I heartily endorse this movement to celebrate her life, work and time in Mandarin.”

Finding images of Stowe from the late 1800s was not difficult. Many photos of her face surround the clay bust of the author in Councill’s makeshift studio. But Councill anticipates some serious detail work to get her dress and and pleats done exactly right.

The model for the White boy in the sculpture is a family member, she said. But the choice for the Black child, detailed down to the single suspender holding up his pants and the slate, was a descendant of Walter Anderson, a lifelong Mandarin resident, World War II veteran and prominent figure in the African American community who has a park named after him on Orange Picker Road, Councill said.

“Choosing a representative boy from the Mandarin community was important, so I chose Eviin (Wilson), who is one of the descendants of one of the oldest Black families in Mandarin,” she said. “That was just a treasure.”

Councill has just started the Stowe figure. Currently, blocks of foam and clay represent a rough approximation of a torso and limbs.

She estimates that it will take until early February to complete the three clay figures, plus the oranges and crate under the boys, which will bear Stowe’s name. The clay figures will be delivered to a foundry, where it will take five months to make the bronze pieces in what is called a “lost wax” process. That is where a mold is made of the clay model, then molten metal is poured into that mold to create detailed statues that match her clay sculpting.

Some time in late July or August, the sculptures will be installed near the restored 1898 St. Joseph’s Mission Schoolhouse for African American Children at Walter Jones Historical Park. Descendents of the Stowe family are expected at the unveiling.

But as the clay design progresses now, the public can watch it being born just steps where Stowe actually lived and walked.

“They can see this literally come to life before their eyes,” Cohill said. “It is so wonderful, and it really brings a sense of place which is so important when you are thinking about the historical narrative. And when you read Stowe’s writings when she was here, the thing I love when I read Palmetto Leaves is that it tells you so much about what the landscape looked like so long ago.”

“This is really a national piece, a gift to the nation as well,” Councill added.

The community is invited to help raise the $150,000 needed to complete the sculpture and move it to the museum. A total of $30,000 has been raised so far.

More information on the project and how to donate can be found at mandarinmuseum.org.

Lead image: Artist Brenda Councill works on the hands of a clay sculpture of a farm boy, part of a life-size bronze statue she is doing of Harriet Beecher stowe for a Mandarin park. | Dan Scanlan, WJCT News 89.9