Long before Rosa Parks, a Jacksonville man had rehearsed the method that would define the mid-century Civil Rights protest movement. The protagonist was the Rev. Andrew Patterson, pastor of Ebenezer A.M.E. Church on Ashley Street and, fraternally, a Prince Hall Mason, who twice placed himself on a streetcar to make the law answer for itself.

In July 1905 he sat in the “white only” section, refused bail and helped the Florida Supreme Court strike down the statewide Avery Streetcar Law, one of the earliest 20th century judicial defeats of a segregation statute anywhere in the South.

When Jacksonville rushed through a substitute ordinance that fall, he tested that too, prompting a second landmark ruling that exposed how quickly Jim Crow adapted at the municipal level. The pattern he embodied, 1. Boycott, 2. Planned arrest, 3. Constitutional challenge, 4. Political workaround, and 5. Retest, became the grammar of later victories, culminating famously with Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott half a century later.

Early life and footprint in Jacksonville

Patterson arrived in Jacksonville from Georgia at the turn of the 20th century with the quiet certainties of a working man and a preacher’s call. A decade later an enumerator found him on Ward Street and, hearing “Patterson,” wrote “Petterson,” one of those small archival dents that time leaves on a life. The ledger called him 30, single, Georgia-born, and a restaurant keeper (own account), living with Lizzie, recorded as head of household, evidence of the threads of kin and small enterprise that stitched together LaVilla’s Black economy.

On his World War I draft card, steady in its hand, Andrew Patterson gave his birth as May 2, 1878, and sketched himself without ornament: Short, of medium build, black hair, black eyes and a local relative, Andrew Watson, to be notified if trouble came.

As Jacksonville hardened its color lines, his steps carried him deeper into the institutions that held his community together. By 1905 he was the Rev. Andrew Patterson, pastor of Ebenezer A.M.E. Church on Ashley Street, a few doors from Broad, where Sunday sermons met weekday organizing. City directories would later catch him at the Masonic Temple, 410 Broad St. fourth floor, “janitor” by occupation, but in truth a caretaker at the center of Black civic life, moving daily through halls where pastors, lawyers, lodge officers, and businessmen planned campaigns and comforted neighbors.

The 1935 Florida State Census found him still rooted in Duval, single at 52. The Florida Death Index records his passing in Jacksonville in 1951, a lifetime spent inside that Broad-and-Ashley corridor, where pulpit, lodge and street met, and where he chose in 1905 and again in 1906 to make law test itself.

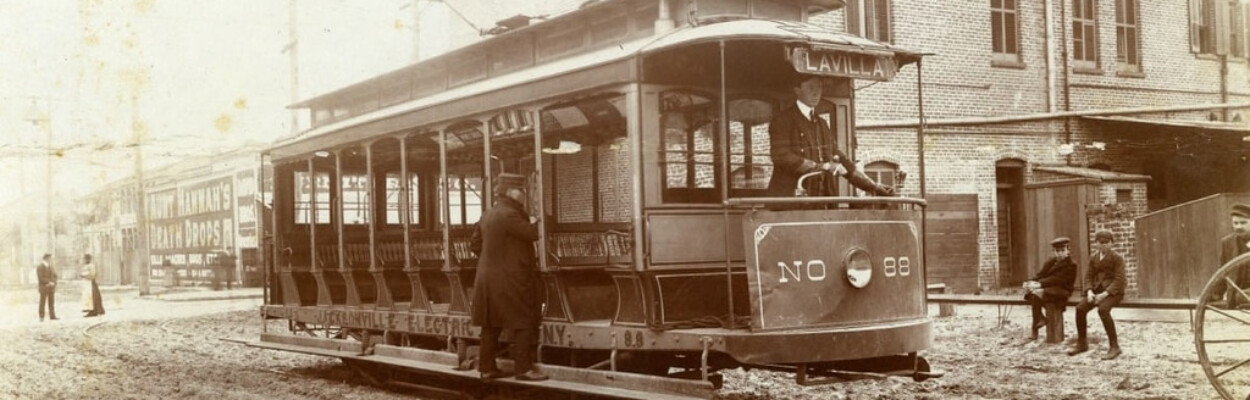

Jacksonville’s 1901 ordinance

In 1901 the city of Jacksonville adopted a streetcar segregation ordinance. The city’s large, politically assertive Black community responded with an immediate boycott, choosing to walk and bicycle instead. Enforcement turned sporadic under the weight of discipline and public pressure. Out of the boycott rose the North Jacksonville Street Railway, a Black-organized streetcar company run by Black motormen and conductors yet open to white riders, hailed in the national press as proof of Black self-help. Along Broad and Ashley, churches and lodges became the switchboards of strategy.

The statewide push: the Avery Streetcar Law (1905)

In May 1905 the Florida Legislature enacted the Avery Streetcar Law, mandating racial separation on all streetcars and carving out an exception for “colored nurses” caring for white children or the sick. Jacksonville’s Black community launched what the Times-Union would call one of the South’s most complete boycotts. Pulpit and lodge synchronized logistics: Walk if you can, share a seat if you can’t, keep your dignity in the meantime.

The test case: State v. Patterson

On July 19, 1905, Patterson boarded a Jacksonville streetcar, deliberately sat in the white section, and submitted to arrest. He refused bail, making a necessity of haste. The next day, attorney J. Douglas Wetmore filed a writ of habeas corpus, arguing that the Avery statute contradicted itself and the 14th Amendment: by granting a privilege to one subset of Black people (nurses) that it denied to others, the law destroyed the equal protection it purported to regulate.

Within days, the Florida Supreme Court agreed. In State v. Patterson (50 Fla. 127; 39 So. 398, 1905), the court held the Avery Streetcar Law unconstitutional and void. Newspapers said the statute was “killed.” For a moment, state-mandated Jim Crow on Florida’s streetcars collapsed, an early, sharp proof that boycott plus bar could move a pillar of segregation.

The counter move: Jacksonville ordinance and second test

City leaders replied with speed. On October 23, 1905, Jacksonville approved a new municipal ordinance compelling separation either by separate cars or divided cars and assigning enforcement as a police duty. Patterson stepped forward again, was convicted in municipal court and sought habeas relief.

In Patterson v. Taylor (51 Fla. 275; 40 So. 493, 1906), the Florida Supreme Court affirmed the ordinance. Segregation for the “peace and good order” of the city, the court said, fell within Jacksonville’s police powers under its charter’s general welfare clause; allowing companies to choose the method of separation was not an improper delegation; and a passenger had no right to a particular seat. The municipal workaround stood, and other Florida cities took note.

Jacksonville wasn’t alone. While Patterson was testing Jacksonville’s ordinance, a companion fight was underway in Pensacola. The resulting Florida Supreme Court decision Crooms v. Schad (51 Fla. 168; 40 So. 497, 1906), also upheld the city’s segregation attempt under the banner of “police powers” and the general-welfare clauses of their charters.

Taken together, the cases showed how quickly Jim Crow reconfigured itself at the city level after the Florida Supreme Court struck the state law. They also prove the movement’s range: this was not a one-city flare-up but a coordinated, statewide pressure campaign of boycotts plus test cases.

Counsel of record: Wetmore and Purcell

J. Douglas Wetmore and Isaac J. Purcell, listed on the briefs as Wetmore & Purcell, were the legal engine of the Jacksonville test. Wetmore, a well-connected Jacksonville attorney and close friend of James Weldon Johnson, framed the equal protection attack that doomed the Avery state law in 1905, seizing on the statute’s “colored nurses” exception as the line that broke equal treatment. Purcell, one of Florida’s early Black attorneys, partnered on the litigation, bridging courthouse advocacy with the city’s Black institutional world, churches, lodges, and business clubs along Broad and Ashley.

The 1905 win and the 1906 retrenchment pushed Wetmore’s name beyond Florida. Black newspapers and civic networks circulated the story as a case study in pairing boycott discipline with constitutional argument. That put Wetmore (and, by extension, Purcell and Jacksonville) in front of two national currents:

- Booker T. Washington’s National Negro Business League: The boycott logistics and the North Jacksonville Street Railway embodied the League’s self-help ethos, showing how commercial organization could buttress legal fights.

- W. E. B. Du Bois and the Niagara Movement (launched 1905): The habeas strategy, refusal of bail, and equal-protection framing resonated with Niagara’s insistence on direct protest and courtroom challenge.

Bottom line: The pairing of State v. Patterson (victory over a state law) with Patterson v. Taylor and Crooms v. Schad (municipal workarounds upheld) became a casebook lesson: win the principle, expect the workaround, prepare the next test. That lesson traveled straight to Rosa Parks and Montgomery.

Pastor on Ashley, Mason on Broad: Sons of Solomon Lodge No. 166

Read in place, Patterson’s choices make even more sense. As pastor of Ebenezer A.M.E. on Ashley Street and a Prince Hall Mason moving daily through the Masonic Temple at 410 Broad, he stood at the crossing of moral authority and organizational capacity. Crucially, he was a member of Sons of Solomon Lodge No. 166 under the Most Worshipful Union Grand Lodge of Florida, a lodge that anchored Black leadership in LaVilla. The church supplied message, discipline, and hope; the lodge supplied networks, meeting space, and logistical spine. Together they sustained the boycott, financed the test case and absorbed the shock of the city’s workaround. In Jacksonville, resistance was not just righteous; it was organized.

Civil Rights legacy: A name we must remember

Andrew Patterson’s stand belongs to the first rank of 20th century challenges to segregation, yet his name largely slipped from public memory. He proved in Florida, in 1905, that a disciplined community could pair boycott economics with a precise constitutional argument and make the highest court in the state blink. He also showed, a year later, how power adapts, and why movements must adapt with it.

The blueprint he helped forge in Jacksonville, church‑anchored leadership, planned arrest, habeas corpus, rapid appeals and readiness for the next ordinance traveled forward to Baton Rouge and then to Montgomery, where Rosa Parks sat and a city walked.

Remembering Patterson restores Florida to the national story and restores a pastor’s courage to the altar of American memory. It reminds us that freedom is not won once but rehearsed, refined, and carried by names that deserve to be spoken aloud.