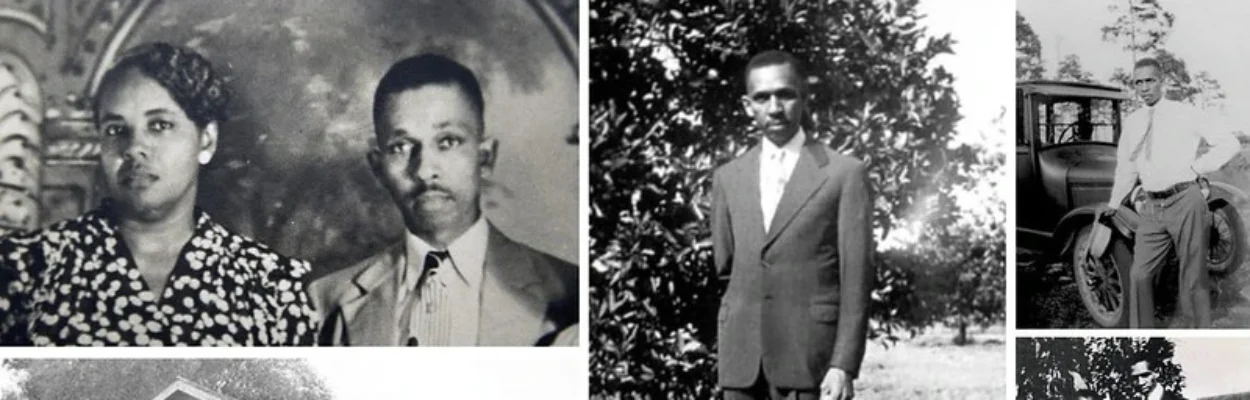

Harry T. Moore (1905–1951) was a pioneering civil rights leader in Florida and one of the earliest leaders of the modern Civil Rights Movement. On December 25, 1951, a bomb exploded beneath the Moores’ home in Central Florida, fatally injuring Moore and his wife, Harriette V. Moore. Their deaths placed them among the earliest martyrs of the modern civil rights era. Moore’s contributions to the movement were significantly shaped by his time in Jacksonville. The following four sites are connected to Harry T. Moore’s experiences in Jacksonville.

1. UF Health parking lot, 720 W. 8th St.

Harry Tyson Moore was born on November 18, 1905, to Johnny and Rosa Moore in the small town of Houston, Florida. Located in Suwannee County, the community was home to his father’s work tending water tanks for the Seaboard Air Line Railroad, in addition to operating a small store out of the front of their house. Tragedy struck in 1914 when his father passed away. Afterward, Rosa Moore supported the family by working in the cotton fields and managing the store, eventually sending Harry to live with one of her sisters in Daytona Beach.

In 1916, Harry moved to Jacksonville to live with his maternal aunts, Jessie, Adrianna and Masie Tyson. Jessie worked as a nurse, while Adrianna and Masie were teachers. The family lived at 2002 Louisiana (now Jupiter) St. in the Sugar Hill neighborhood. Their two-story wood-frame duplex stood across the street from Darnell-Cookman Elementary School (Public School No. 45), on the northwest corner of Louisiana and Arch streets. The home was later razed along with much of the surrounding Sugar Hill neighborhood. Today, the former residence site is a surface parking lot at 720 W. 8th St., owned by UF Health Jacksonville.

2. Old Stanton High School, 521 W. Ashley St.

Moore’s years in Jacksonville were his most formative. Jacksonville. with its large Black community with a proud tradition of independence and intellectual achievement, proved to be pivotal to his racial and political awakening, according to his daughter.

While living in Jacksonville, Harry attended Stanton High School in LaVilla. Designated to the National Register in 1983, Stanton was Florida’s first official school for African Americans. Opened in 1869, the school was named in honor of Gen. Edwin McMasters Stanton, an outspoken abolitionist and secretary of war under President Lincoln during the Civil War. In 1877, President Ulysses Grant visited the school during a tour of Florida. During the visit, a 6-year-old student named James Weldon Johnson raised his hand from the crowd and Grant shook it. Johnson would go on to become the school’s principal in 1894 and expanded it to become the only high school for African Americans in the city.

While serving as the principal, Johnson wrote “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” which his brother Rosamond put to music. The song would later become known as the Negro National Anthem. The Johnson brothers relocated to New York City in 1902, James Weldon Johnson becoming a nationally famous songwriter, author, poet, diplomat and civil rights orator.

As a result of one of the first civil rights legal cases in Jacksonville and the South, the historic three-story brick schoolhouse was constructed in 1917. Harry T. Moore was enrolled as a student at Stanton when the building on West Ashley Street originally opened and would have been exposed to the civil-rights case that resulted in its construction.

After three years in Jacksonville, he returned to Suwannee County, where he graduated from Florida Memorial College and was nicknamed “Doc” by his classmates.

3. Citizens Insurance Building, 326 Broad St.

Moore moved to Brevard County in 1925 to accept a position teaching fourth grade at Cocoa’s only Black elementary school. There, he met Harriette Vyda Simms. A former teacher, Harriette was working as an insurance agent for the Atlanta Life Insurance Co. The two soon married.

In 1934, Moore founded the Brevard County branch of the NAACP. Three years later, working in conjunction with the all-Black Florida State Teachers Association and with legal support from NAACP attorney Thurgood Marshall in New York and Jacksonville attorney Simuel D. McGill, Moore initiated the first lawsuit in the Deep South seeking equal pay for Black and white teachers. His close friend John Gilbert, principal of Cocoa Junior High School, courageously volunteered to serve as the plaintiff.

Simuel D. McGill had established the prominent Jacksonville law firm McGill & McGill with his younger brother, Nathan K. McGill. Nathan later relocated to Chicago, where he became a prominent attorney and served as legal counsel for the Chicago Defender, a Black newspaper.

At the time of the case, their offices were located in the Citizens Insurance Building. A 1902 graduate of Edward Waters University, McGill earned his law degree from Boston University in 1908 before returning to Jacksonville to open his practice. One of the most prolific civil rights attorneys in the pre-World War II era, he handled numerous NAACP cases during Moore’s tenure with the organization.

4. Jacksonville Terminal, 1000 Water St.

On Christmas night in 1951, Harry T. Moore and his wife, Harriette Moore, were victims of a bombing at their home. Harry died en route to the hospital, and Harriette succumbed to her injuries nine days later. During the investigation into their deaths, Harry’s mother, Rosa Tyson, a Jacksonville resident who had been visiting her son for Christmas, was interviewed. She recounted a frightening incident in which Harry and John Gilbert were followed from Brevard County to Jacksonville:

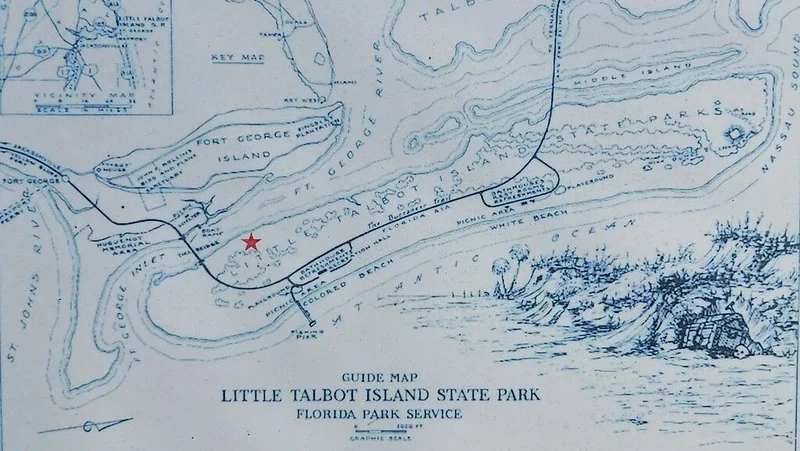

“At one point Ms. Tyson interjected that several years ago Harry had come to Jacksonville with a friend, John Gilbert, of Bartow. Gilbert worked in Bartow as a representative of the Central Life Insurance Company (Gilbert went into insurance after losing his education job due to the 1930s NAACP case). Harry advised Ms. Tyson that they had been followed by two white men all the way from Mims to Jacksonville. According to Ms. Tyson, Harry stated that they had stopped twice at two filling stations and sought the advice of the attendant as to what they should do to lose their followers. Both times they were advised to remain at the station until the followers left. Each time Harry and Gilbert did that, the car would catch up with them. One of the attendants suggested that they go on to Jacksonville but not to their intended destination but rather to go someplace like the railroad station and lose themselves in the crowd. Harry advised Ms. Tyson that they did go to the railroad station where the lost the two men. Harry did not describe the two men.”

Source: Frank M. Beisler, senior investigator for the Office of the Attorney General Civil Rights Division, and C. Dennis Norred, special agent supervisor for the Florida Department of Law Enforcement

Coming Soon: Jacksonville’s Gullah Geechee Heritage

A Community Story. A Cultural Record. A Call to Remember.

Jacksonville’s Gullah Geechee Heritage, a new book by Ennis Davis and Adrienne Burke, will be released by Arcadia Publishing on April 28, 2026.

Jacksonville’s Gullah Geechee history lives in the land, the water, the neighborhoods, and the memories passed down through generations. Jacksonville’s Gullah Geechee Heritage brings those stories forward, rooted in place, shaped by community and preserved for the future.

“An invaluable resource combining extensive research, lived experience and generational knowledge inherited directly from within the culture providing a variety of fresh insights into a truly unique mixture of faith, community, ingenuity and resilience that is definitively Gullah Geechee.”

— Ted Johnson, National Park Service, retired

Order your signed copy today

Preorder signed copies of Jacksonville’s Gullah Geechee Heritage, available in hard and soft cover.