The National Hurricane Center is becoming more interested in a tropical wave in the mid-Atlantic. Some long-range computer models are also picking up on the possibility of the system developing and moving toward the Caribbean over the weekend or early next week.

The wave is taking a more southerly track than other disturbances we’ve seen this month, which could give it a chance of getting past the persistent Saharan dust. Saharan dust can choke tropical systems before they get a chance to develop.

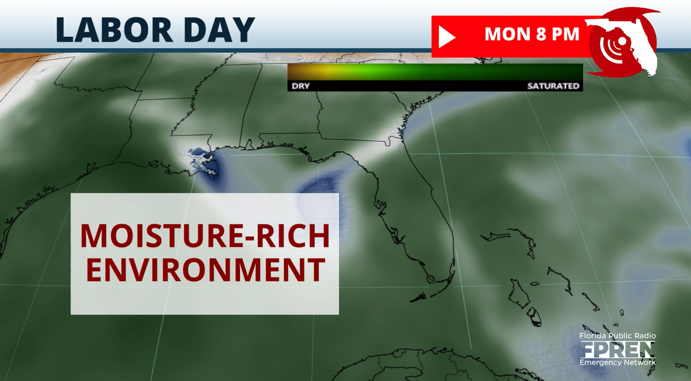

If the disturbance ducks the dust and makes it to the Caribbean islands, it appears the environment will become more favorable for development. But the Hurricane Center says that could take about a week to happen. For now, development isn’t likely over the next several days. And so far, there’s not much to look at yet.

The Saharan dust travels more than 5,000 miles from Africa every year. NOAA started tracking the annual dust storms about 20 years ago. The storm is also roughly the size of the lower 48 in the United States, making it one of the larger Saharan Dust storms tracked in recent history.

Saharan dust helps weaken or suppress tropical cyclone formation and intensification, according to the National Weather Service and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Saharan dust has been found in virtually all parts of the globe — even atop glaciers and near both poles.

NOAA uses a combination of land-based stations, satellites and the hurricane hunter aircraft to collect and measure data for the Saharan Dust storm each year. Studies on the effect of the storms help researchers understand how the size of each year’s storm can affect the atmosphere as well as the Atlantic hurricane season for that year.

A hot topic of conversation these days seems to revolve around the hurricane season and what appears to some to be a slow start. One of the most obvious factors that is keeping African tropical waves from organizing and crossing the Atlantic is the Saharan dust.

According to the National Weather Service, the dust is nearly 60% to 70% dustier or thicker than normal. Several of the disturbances that have moved off the African coast are leaving the coast farther north than normal as well, so they are running straight into the Saharan dust as opposed to traveling below the dusty deck.

The sea surface temperatures off of Africa at these northern latitudes is also a lot colder than further south. Cooler ocean temperatures will also severely limit tropical systems from developing.

Also, the upper atmosphere over the Atlantic is unusually warm, which means there isn’t much of a contrast between the ocean and the air loft. The difference in those temperatures is what helps build thunderstorms. This wouldn’t stop storms from developing, but it could slow the trend of storms trying to develop, albeit slightly.

Whatever is driving the current weather pattern, the odds still favor hurricanes developing in September and October. They will intensify more quickly than average due to the warm ocean and end up being stronger.

It’s important to note that about 80% of tropical systems that develop tend to do so starting in September. And it’s been an above-average season so far in terms of the number of Category 3-plus hurricanes. Since June 1, there have been five named storms, and the projections from the National Hurricane Center call for up to 15 or 20 more storms this season.

There’s a growing consensus that we won’t see an off-the-charts number of named storms as earlier forecast this season. But what’s more important than that is how many hurricanes develop.

So far, the 2024 season has already had three hurricanes. Another six to 10 developing, even if no threat to land, is certainly possible given the extremely warm Atlantic water and a strengthening La Nina.