In the disastrous aftermath of Hurricane Matthew in 2016, a 7-foot storm surge inundated St. Augustine.

The receding tide left behind millions of dollars in damaged property, including about 1,000 historic buildings, some in the historic Downtown dating back as far as the 18th century. That’s to say nothing of the people in flood-ravaged neighborhoods like Davis Shores.

How can the bayfront city shore up defenses to keep residents — and the culturally rich buildings that the city’s tourism relies on — safe?

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is devoting years and millions of dollars to answering that question, with recommendations for St. Augustine expected in 2028.

How do you keep a coastal city dry?

After Matthew and then Hurricane Irma in 2017, the city of St. Augustine started serious conversations about how to improve its resiliency.

“Hurricane Matthew kind of brushed our community,” St. Augustine Chief Resilience Officer Jessica Beach tells Jacksonville Today. “It was 80 to 90 miles offshore, so we did not have a direct hit, but we had a lot of flooding. I think that was a wakeup call for our community because we had not really had impacts from flooding of that magnitude in decades.”

In recent years, even when a hurricane isn’t bombarding the coast, St. Augustine is experiencing worse flooding than normal.

“We had flooding — not as extensive as Hurricane Matthew — and then if you fast forward, we have high-tide ‘nuisance flooding’ already that we’re dealing with in our streets,” Beach says. “The hurricanes are the more severe storms that create more damage, but we’re dealing with this flooding already, and for the past several years it’s been a challenge.”

Facing sea level rise that’s expected to get worse, St. Augustine reached out to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. After a few years of waiting to get a study approved, the corps started its examination last year of what infrastructure can best protect St. Augustine well into the future.

“It’s addressing a huge issue that will affect everybody who lives in the St. Augustine area and will live in the St. Augustine area for the next 50, 60, 100 years,” U.S. Army Corps of Engineers spokesman David Ruderman tells Jacksonville Today.

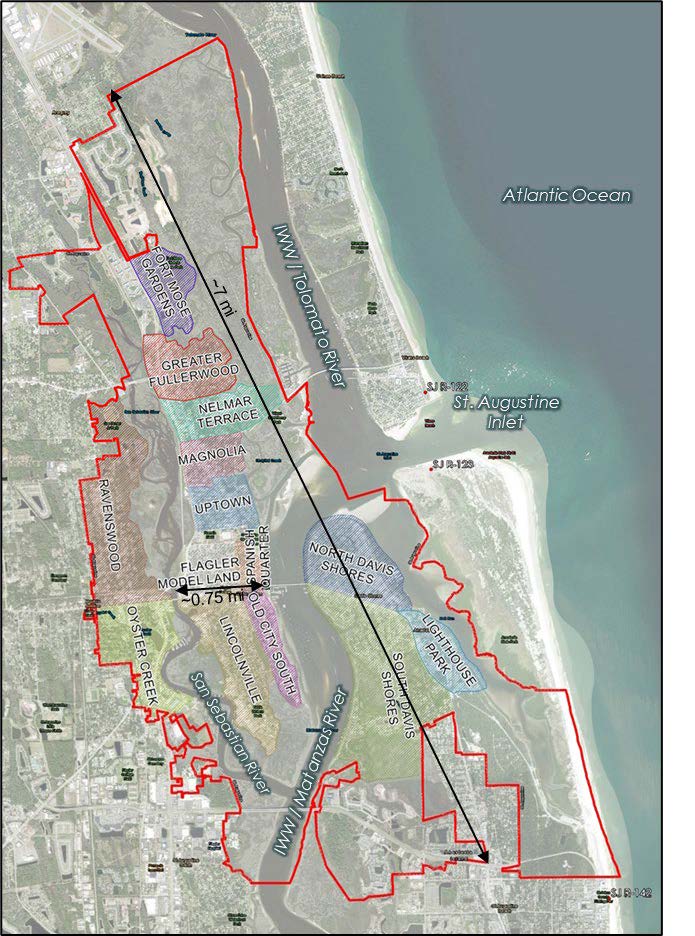

The study is known as the St. Augustine Florida Back Bay Coastal Storm Risk Management Feasibility Study. The “Back Bay,” Ruderman explains, is “not the coast, but the water in between the barrier island and the mainland.” It’s a large undertaking, because there’s a lot of area to look at along the Matanzas, Tolomato and San Sebastian rivers.

The study officially started 18 months ago, but he says they’re just finishing “the first inning.”

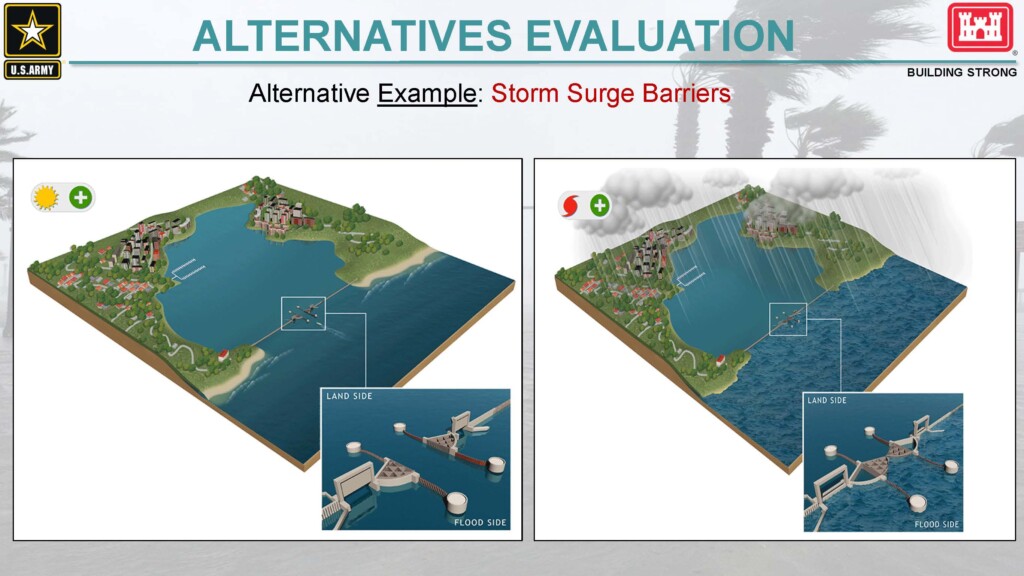

Using data from past storms, scientists with the corps are modeling a number of scenarios and what kind of damage they would leave in St. Augustine. The projections are a step in creating a response plan, but it’s too soon to say exactly what solutions might look like, Ruderman says.

“There’s so many checks and balances, and so much nuance put into a study like this over a period of time. You’re not going to slapdash, ‘Let’s put a wall here, and some mangroves here, and hope for the best,’” he says.

What is complete is the “FWOP,” or “future without project” modeling, showing what St. Augustine might look like without any intervention.

Projecting through the year 2084, the Army Corps estimates an intermediate scenario of sea level rise and storm damage could leave the city with $225 million in damage — and that’s not factoring for 70 years of inflation.

So, the study can’t result in a solution that will need to be replaced in five or 10 years. Forget 2024 — they’re thinking about 2084.

“It’s an enormous study,” Ruderman says. “It’s very complex.”

Protecting people, not just buildings

Daniel Oconnell sold his longtime home on Anastasia Island after Hurricane Irma buzzed up the Florida peninsula in early September of 2017.

“I was the second home that was built on the street I lived on,” he says. “I built it in 1985.”

Nowadays, he lives in The Villages. He loved living in St. Augustine, he tells Jacksonville Today, but he just couldn’t put up with any more flooding.

Besides protecting the Castillo de San Marcos fort and the rest of Downtown’s historic treasures, the Back Bay study is also aimed at keeping more people from feeling the need to flee

“People tend to think of the historic Downtown core first, and obviously we have a lot of cultural historical resources at risk and you can’t really replace those,” Beach says. “At the same time, we have an entire community that is in need, and some of those residential areas that are outside the historic Downtown that are flood prone, they need help, too. This was our opportunity.”

In addition to the Army Corps of Engineers’ ongoing project, the Florida Department of Transportation is working with St. Augustine in the short term to improve the city’s seawall along A1A next to the fort.

Construction is planned to begin by the end of 2025 to fix years of wear-and-tear and to raise the wall’s height from 6.7 to 8.5 feet.

Get involved

To get involved in the Army Corps of Engineers project, the public is invited to monthly webinars as well as in-person town halls to provide input. At this stage of the study, the Army Corps of Engineers wants to know what neighborhoods around St. Augustine are experiencing.

What kind of flooding have you seen in recent years? When does the water rise? These are the questions the Army Corps needs answers to to determine the importance of using federal funding to keeping St. Augustine above water.

The next webinar takes place at 1 p.m. on Wednesday, June 20, via WebEx. Join the live stream or join by phone at 1-844-800-2712 with access code 199 927 9909.

More information on the Back Bay Study, including videos of past meetings, is here.

The next in-person meeting, when St. Augustine locals can hear directly from the Back Bay study team and provide feedback, is planned for some time in October.