From Timucua two-spirits to bisexual blues musicians to the continued celebration of River City Pride, Jacksonville has a long and storied LGBTQ history. In honor of Pride Month, The Jaxson takes a look at six stories from the city’s past with special significance for the LGBTQ community.

Timucua two-spirits

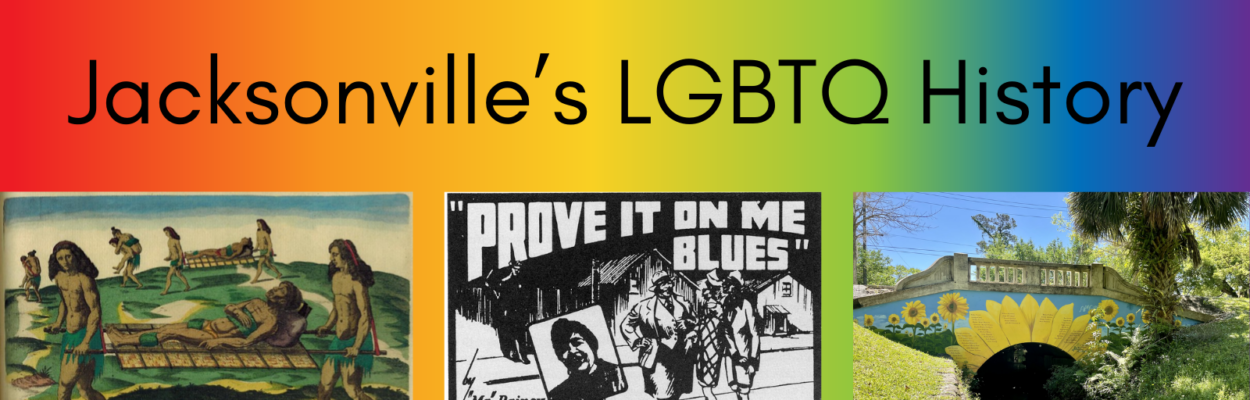

“Two-spirit” is a modern term for Native American people who belonged to a third, nonbinary gender. Historically, most native peoples in the present-day U.S. and Canada recognized one or more genders that played distinct roles from the roles of men and women. The Timucua of what’s now the Jacksonville area were no exception; in fact, the earliest substantial records of two-spirit people come from the Timucua at the time of the French colonization of Florida in the 1560s.

The term two-spirit does not refer to a person’s physical anatomy, but to their gender, which is characterized by social roles and varies from culture to culture and person to person. Among the Timucua, two-spirits had duties and a style of dress that distinguished them from men and women. Like women, they wore skirts and kept their hair down; they also wore their own color of feathers.

Timucua two-spirits’ duties included transporting supplies and weapons and carrying the wounded and dead from battle. They also tended to the sick and prepared the dead for burial, indicating they played a role of deep spiritual significance in Timucua society. In addition to the two-spirit gender role, contemporary Spanish sources indicate that same-sex relationships between men and women were common and accepted among the Timucua well into the colonial period.

Jacksonville’s rainbow blues

In the first decades of the 20th century, Jacksonville was an epicenter of blues, jazz, and ragtime music. The neighborhood of LaVilla in particular was later dubbed the “Harlem of the South” for its vibrant Black music culture. Throughout the period, LGBTQ performers played crucial roles in cultivating Black music and bringing it to mass audiences.

The first known instance of the blues being sung on stage anywhere in the world happened in Jacksonville, and the performance has an LGBTQ connection. In April 1910, Professor Johnnie Woods performed at the Airdome on Ashley Street in LaVilla. During the show, Woods, a ventriloquist, had his dummy “Little Henry” get drunk and sing the blues in an act reviewed by the Indianapolis Freeman. In addition to his ventriloquist act, Woods was also a tap dancer and “female impersonator,” or drag performer. There’s no evidence Woods himself was queer, but his gender-bending act certainly pushed the envelope.

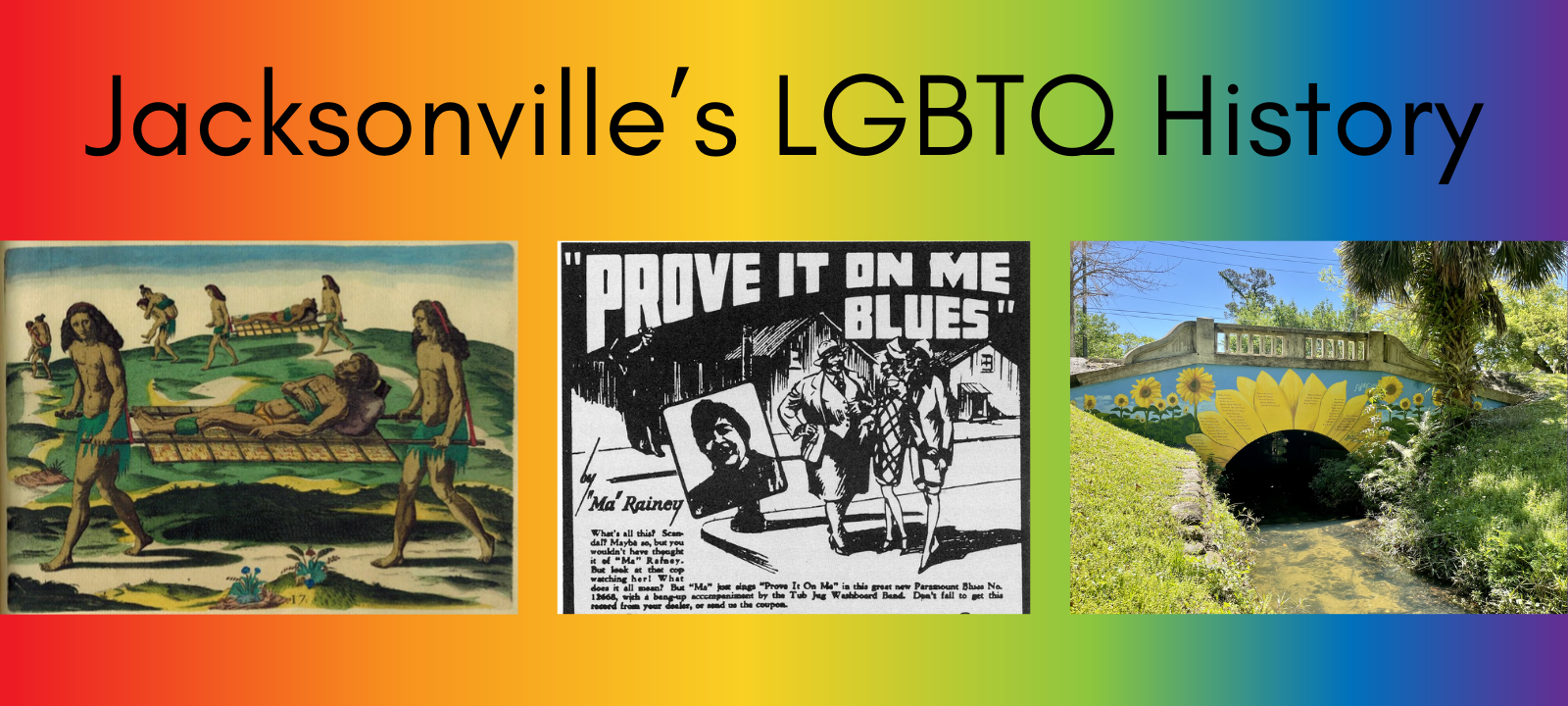

In 1906, legendary blues singer Gertrude “Ma” Rainey moved to Jacksonville to join Pat Chappelle’s LaVilla-based Rabbit’s Foot Company along with her husband William. As part of one of the largest Black vaudeville troupes, the Raineys traveled extensively throughout the South and beyond, spreading the popularity of the blues as a musical style. Ma Rainey, known as the “Mother of the Blues,” was bisexual and invoked same-sex romance and cross dressing in several of her songs. Reportedly, Rainey was arrested in 1925 after police raided a raucous party and found her and her chorus girls in a state of drunken undress. Researchers suggest the incident inspired Rainey’s 1928 song “Prove It On Me Blues,” in which she sang:

They say I do it, ain’t nobody caught me

Sure got to prove it on me;

Went out last night with a crowd of my friends,

They must’ve been women, ’cause I don’t like no men.

–Ma Rainey, “Prove It On Me Blues,” 1928

One of Rainey’s reported lovers was Bessie Smith, who Rainey brought into the Rabbit’s Foot Company in LaVilla in the 1910s. Smith, later known as the “Empress of the Blues,” was openly bisexual and had relationships with several women, including a tumultuous affair with chorine Lillian Simpson.

LGBTQ in the Navy

Since the days of U.S. founding father Baron von Steuben, LGBTQ people have served with distinction in all branches of the U.S. military. Jacksonville became a major military city in 1940 with the establishment of Naval Air Station Jacksonville, then and now one of the largest naval air bases. This was followed in 1942 by a major sea base, Naval Station Mayport. In addition, Jacksonville became a major hub for the Navy WAVES, the Navy’s women’s branch. WAVES helped staff the bases while the men were needed for sea duty.

Same-sex relations were grounds for discharge in the U.S. Navy, but the presence of sailors and WAVES from all over the country allowed for secret parties and gatherings. Records indicate that significant numbers of LGBTQ service members served in Jacksonville in the 1940s. This was likely the first time in Jacksonville history that LGBTQ people could gather in an organized way.

A local man known by the pseudonym Tom Bell, who later served in the Army, hosted parties for gay and lesbian service members at his residence. A local lesbian known pseudonymously as Doris also hosted parties at her place. Other parties were held at Downtown’s Hotel Roosevelt (now the Carling residential tower). Until this point, Jacksonville had few if any gay bars or venues, and these parties for LGBTQ service members prefigured the later clubs and bars that started popping up in Jacksonville after the war.

LGBTQ people have been able to serve openly in the U.S. military since 2011. Today, the Navy has the most LGBTQ service members of any branch, with 9.1% of the Navy identifying as LGBTQ.

Gay clubs in Jacksonville history

Jacksonville has been home to bars, clubs and other venues catering to the LGBTQ community since at least the 1950s. At a time when being out came with huge social stigma and even personal danger, these spaces served as safe havens for LGBTQ Jaxsons to meet, find a date or simply be themselves in public. While online dating and broadening acceptance of LGBTQ people in the wider community has led to a decline in the number of gay bars and nightclubs, their role in Jacksonville’s LGBTQ history can’t be overstated.

By 1960, Jacksonville was home to at least three gay bars. In 1964, Roverta “Bo” Boen opened what became Duval County’s longest-running gay bar, Bo’s Coral Reef. Originally located on Beach Boulevard in Jacksonville Beach, Boen later moved it to Philips Highway. In 1980, Bo’s returned to Jacksonville Beach in a building on 2nd Street. For nearly 40 years, it was a favorite hangout for LGBTQ people from across the First Coast and a popular spot in the Jax Beaches bar scene. Bo’s Coral Reef survived Boen’s death in 2010 and carried on until 2019, when it finally shuttered after 55 years serving the community.

Club Jacksonville was a bathhouse catering to gay men located in a windowless building at 1939 Hendricks Avenue in San Marco. While communal bathhouses fell out of favor with most of the general population in the early 20th century, they remained popular in the LGBTQ community as spaces for members to meet and hook up without fear. The building began as the Roman Spa in 1973 before becoming Club Jacksonville in 1979, and for another 40 years the spa was a neighbor to Southside Baptist Church and several nearby businesses. Membership declined in its later years and it finally closed in 2019 due to compounding code citations stemming from long-neglected maintenance. The building was then renovated as the headquarters of the architectural firm Group 4 Design.

Another long-running LGBTQ business was the Metro, a massive entertainment complex on Willow Branch Avenue in Riverside. Opening in 1993, the sprawling 17,000-square-foot complex had rooms with a variety of themes and became one of the largest nightclubs in the city. It closed in 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the overall decline in gay clubs.

Today, Park Place on Riverside’s King Street holds the distinction as Jacksonville’s oldest operating gay bar. A pioneer of the King Street District at a time when the area was seen as rough, Park Place took on its identity as a gay bar in the 1990s and has witnessed the street’s transformation into a popular entertainment strip. Despite a decline in classic gay and lesbian bars, recent years have seen the rise of a number of LGBTQ businesses carry on the tradition in a variety of interesting niches, including Alewife Craft Beer Bottle Shop, Dart Bar & Games, Hardwicks Bar, Incahoots Night Club, and The Greenhouse & Bar.

David, Jacksonville’s trailblazing gay magazine

From 1970 to 1974, Jacksonville was the headquarters of the first magazine ever to serve Florida’s gay community. The brainchild of editor-in-chief Henry C. Godley and managing editor Mark W. Riley, David was a pioneering monthly lifestyle magazine that advertised its mission as “entertaining and informing gays.” Initially focusing on Florida and Georgia, David distinguished itself by covering a wide array of topics of interest to the gay community, with its editors stating, “David is not a homosexual newspaper – but a newspaper for homosexuals.”

David contained pieces on LGBTQ events, news stories, travel pieces and features on topics ranging from club reviews to politics. The magazine printed a letter from Harvey Milk, the first openly gay man elected to office in California, and covered Florida Attorney General Robert L. Shevin’s efforts to overturn laws long used to cudgel LGBTQ people. One article detailed Jacksonville’s growth as a destination on “the circuit” of gay bars and clubs between Atlanta and Miami. “In the past, the travellers on the circuit by-passed Jacksonville,” the author wrote. “Three years ago there were only two gay bars or nightspots for the crowd to visit. Today there are at least five.” Jacksonville venues mentioned in the piece include the Knight Out, the Commodore, the Off-Beat, the Tides Inn, Wh-oo Bottle Club, the Crow-Bar, the A-Go-Go Club’s Den, and the legendary Bo’s Reef.

David’s profile grew quickly, and its distribution and coverage spread to encompass the Southeast. In 1972, the magazine launched its own drag competition, the Miss David contest, which was subsequently joined by a Mr. David competition. The contests grew into an annual convention held in various cities. In 1974, Godley and Riley relocated the magazine to Ft. Lauderdale, where they established the International David Society, which offered an array of services for LGBTQ customers including travel agents and health insurance.

David ultimately fell victim to its own success. By proving there was a market for quality LGBTQ lifestyle and travel publications in Florida and the Southeast, it opened the door for competitors who siphoned off its advertisers. David’s publishers pivoted to different formats, but the magazine never regained its early prominence. The International David Society was dissolved in 1990, bringing a final end to the historic magazine. In recent years, historians of LGBTQ publications have begun chronicling David’s history and impact, giving it its proper due as the Southeast’s trailblazing gay magazine.

Willowbranch Park: Jax’s LGBTQ holy ground

Willowbranch Park and the adjacent Willowbranch Library have had a place in Jacksonville’s LGBTQ history for six decades. The site of thousands of hushed meetings and boisterous celebrations over the years, one local pastor describes it as “holy ground.” The park dates to 1916, when it became a new public space in an expanding part of Riverside. The Mediterranean Revival-style library opened in 1930 as the city’s third branch library, after the main Downtown library and Wilder Park Library in Sugar Hill, which served African-Americans during segregation.

A comparatively well-to-do neighborhood in the early 20th century, Riverside saw its housing values drop in the 1960s as white flight and suburbanization led tens of thousands of Urban Core residents to move to newer, more remote developments. However, Riverside’s cheaper rents drew in a more bohemian element, and soon the neighborhood was full of musicians, artists, hippies and LGBTQ folks from far and wide. Thus, Riverside became Jacksonville’s first substantial “gayborhood,” and residents hosted the city’s first Gay Pride Festival, a picnic in Willowbranch Park in 1978, nine years after the Stonewall Riots in New York galvanized the gay rights movement. While Jacksonville’s early Pride celebrations received pushback from community reactionaries, they succeeded in increasing the visibility of LGBTQ people. River City Pride evolved into the massive celebration it is now each October (to beat the June heat of Pride Month) featuring a parade and several days of revelry across Riverside.

Willowbranch Library has its own LGBTQ history. At a time of severe oppression, the library became a popular spot for LGBTQ Jaxsons to meet and organize in relative safety. Among those who met here were the founders of LGBTQ youth organization JASMYN, today one of Jacksonville’s most prominent LGBTQ nonprofits. JASMYN traces its roots to 1992, when teenager Ernie Selorio left a note seeking solidarity on the library’s bulletin board. Selorio had been outed when his mother found his journal, and feeling isolated and alone, he asked others to meet him to form an LGBTQ youth support group. About 10 people turned out for the first meeting, and JASMYN was born. Now based in nearby Brooklyn, JASMYN continues to provide support to LGBTQ teens and young adults across the city.

In the 2010s, organizers and the city launched a renovation of Willowbranch Park dedicated to its long LGBTQ history and to victims of the AIDS epidemic that devastated the gay community in the 1980s and ’90s. Volunteers began reforesting the park along Willowbranch Creek to create Love Grove in honor of Riversiders lost to AIDS, and they sponsored a sunflower mural painted on the culvert where the creek flows under Park Street. Advocates hope to add more public artwork to create Florida’s second AIDS memorial.