Known as the District of Soul, Moncrief is a historic neighborhood located a few miles northwest of Downtown Jacksonville. Here are five interesting historical stories related to the special place with a unique past.

1. The legend of Moncrief Springs

The neighborhood of Moncrief is named after a spring that once flowed along Moncrief Creek. According to legend, the spring was named after wealthy French pawnbroker Eugene Moncrief. Folklore claims Moncrief escaped the French Revolution with a diamond necklace belonging to Marie Antoinette and found refuge in Florida. Moncrief was said to have then buried several chests of jewels near the springs upon arriving in the area in 1793.

He was soon acquainted with the local native people and fell in love with a beautiful maiden named Sunflower. Moncrief was so smitten that he went into the spring and soon emerged with one of his small chests. He opened it and Sunflower plunged in with both hands to touch all of the beautiful colorful stones and gold pieces. After some time she chose a couple of pieces to adorn her own neck, and as night fell, she headed back down the trail to her own home. Eugene couldn’t have known the jealous rage that awaited at the end of that trail, as a native warrior named Gun Powder set his sights on Moncrief’s head. Within a month, Moncrief was scalped, leaving the location of his remaining chests of jewelry forever unknown.

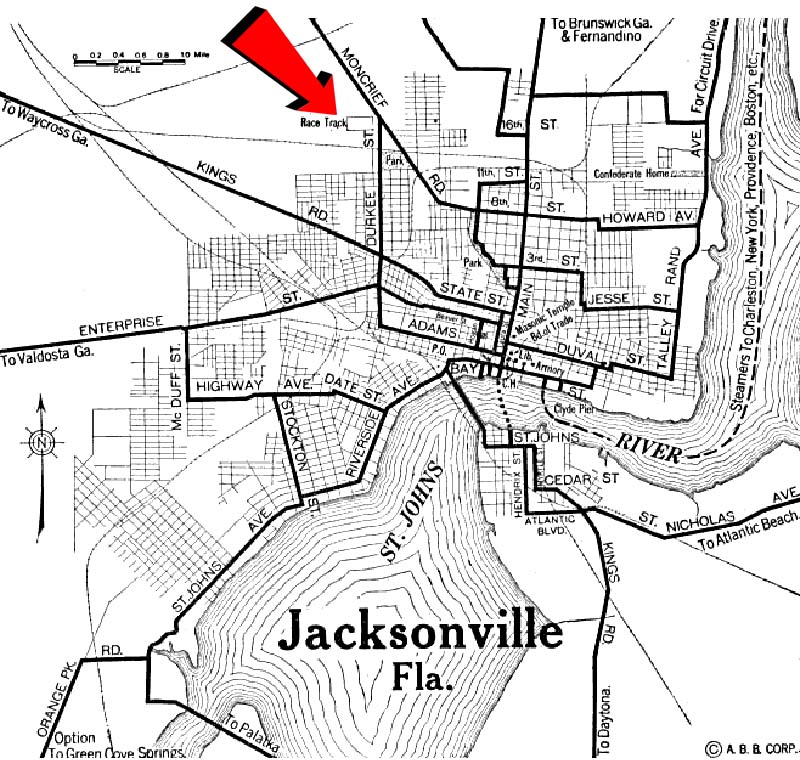

The land around the springs was developed into a tourist attraction called Moncrief Park during the 1870s. During its initial years, Moncrief Park included a racetrack, dancing pavilion, bowling alley, baseball field, restaurant and bath houses. To connect his attraction to the city, its developer built a toll road called Moncrief Road, which was the third paved road in the city.

2. The Belmont of the South

In early 1909, led by lumber mill owner Thomas V. Cashen, a group of Jacksonville businessmen established the Florida Live Stock & State Fair Association with $150,000. Their intention was to construct a horse racing facility that would make Jacksonville the winter racing center of the South.

When their Moncrief Park horse racing facility opened, it was the first race track in the Southeast and considered one of the best in the U.S. Races were held every day except for Sunday during the winter. An estimated 6,000 racegoers were in attendance on opening day. When the gates opened on Thanksgiving Day 1909, between 9,000 to 10,000 people attended.

During its operation, the track proved to be an economic asset for Jacksonville. Its promoters estimated that the economic benefit for Jacksonville merchants was over $4 million in trade during the 110-day racing season. By 1910, New Yorkers were calling Moncrief the Belmont of the South and Jacksonville was being promoted as the place to go on vacation. Furthermore, the historic American Derby, now held annually at Arlington Park near Chicago, was initially held at Moncrief Park.

The last race was held on April 1, 1911. Two weeks after the race, local newspaper editorials denounced horse racing as events that only attracted one class of people who lived off the residents as parasites. In Spring 1911, the Florida Senate passed a bill prohibiting all racetrack gambling by an overwhelming vote of 62 to 1. After the race track closed, the property was sold and redeveloped in 1914 into a residential subdivision that is now the neighborhood of Moncrief.

3. The Point

Prior to the 1960 opening of Interstate 95, Moncrief Road was the main thoroughfare connecting Northwest Jacksonville’s neighborhoods to Downtown. Situated at the heart of the Moncrief neighborhood, the intersection of Myrtle Avenue, Moncrief Road, West 25th and 26th Streets was once known as The Point. From the neighborhood’s formative years until the 1930s, this is where two branches of Jacksonville’s streetcar system, the Davis Street Line and the Myrtle Avenue Line, met. With the direct connection into Downtown, the neighborhoods of Moncrief, Durkeeville and Sugar Hill developed as early 20th century streetcar suburbs. As a result, the commercial district surrounding this intersection is an early example of transit oriented development.

4. Where the curly fry was invented?

The historic commercial district clustered around The Point is home to Holley’s Bar B Q, a Jacksonville culinary institution. Established by Jack Holley in 1937, Holley’s is the city’s oldest continuously operating barbecue restaurant in town. In addition, Holley’s is said to be the place where curly fries were invented!

“My dad’s brother Leroy made the machine that curled the fries. I could dig it up. My dad could have had a patent on it, but he couldn’t read nor write, so he got bamboozled.”

– Wendy Holley

That little-known bit of Jacksonville history comes from the recently published book by Mark Winne, Food Town USA, Seven Unlikely Cities That Are Changing The Way We Eat. Despite not being officially credited with the invention or largely promoted by the mainstream, Holley’s continues its tradition of serving up ribs with curly fries on the side.

5. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. comes to Moncrief

The home at 1353 W. 33rd St. is a mid-century ranch built in 1958. It was the residence of community leaders Isadore and Mary Littlejohn Singleton. On March 19, 1961, Dr. Martin Luther King delivered his “This is a Great Time to Be Alive” sermon at Durkeeville’s Mt. Ararat Missionary Baptist Church. Speaking at an event sponsored by the Duval County Citizens Benefit Corporation and the Interdenominational Ministerial Alliance, King delivered a message centered around the promotion of nonviolent resistance.

Following the event, King was escorted to the Singletons’ residence to meet with local African American civic leaders, and his visit was credited with inspiring African Americans to continue their quest for local political offices.

In following years, Isadore Singleton attempted but was unsuccessful in his bids for a seat on City Council. However, in 1967, Mary Eleanor Littlejohn Singleton and Sallye B. Mathis became the first Black women elected to the Jacksonville City Council.

Contact Ennis at edavis@moderncities.com.