The evidence has been clear for years: Florida is in a housing crisis.

The crisis affects more than the poor; it also is hurting the middle class, including the workers who provide essential public services, like police officers, firefighters and teachers.

In a March poll by the University of North Florida, housing costs ranked No. 1 as “the most important problem facing Florida today.”

The problem

It’s a classic issue of supply and demand — not enough housing is available for Florida’s surging population, so the price of housing increases. Here are some examples of the affordable housing crisis from the Florida Housing Coalition:

— Over 2 million Floridians pay over 30% of their income for housing.

— About 900,000 Floridians spend over 50% of their income on housing.

— For every 100 extremely low-income Floridians, there are only 25 affordable and available housing units.

— The price of a typical home in Florida rose from $140,000 in 2012 to $403,000 in 2022, reported Bankrate, while incomes in Florida have not kept up. That means, the median home that a Floridian can afford fell from $267,600 in 2017 to $238,800 in 2021. What’s worse, too few homes in the median price range are being built.

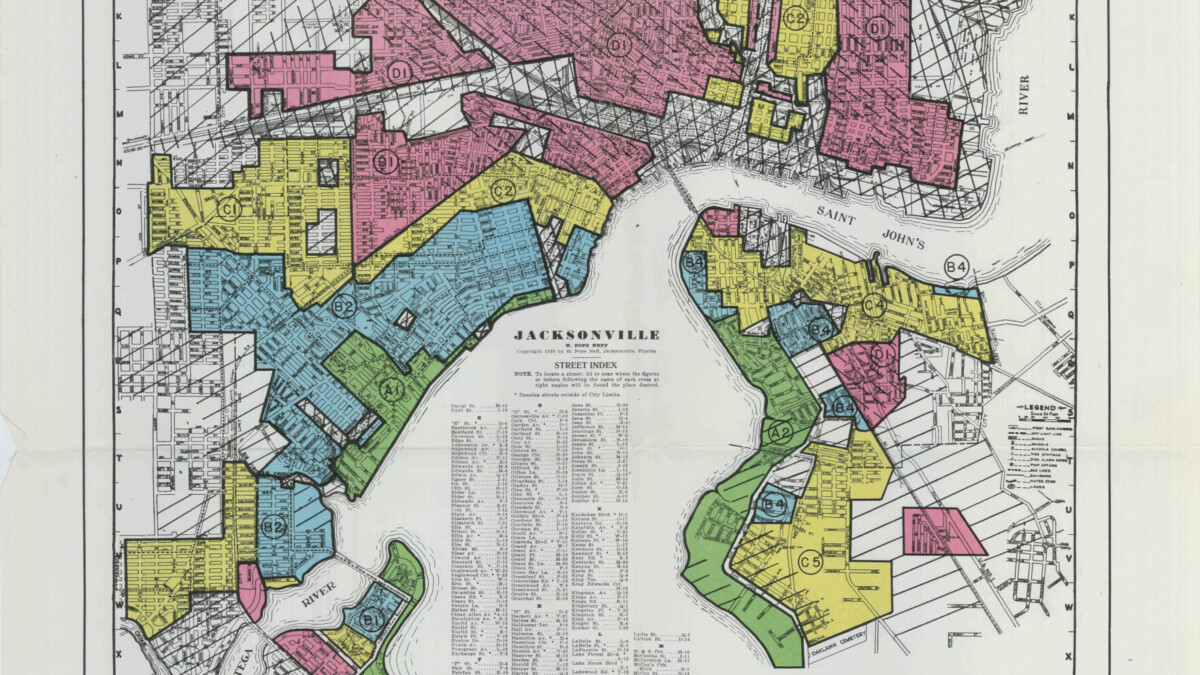

— Black and Hispanic Floridians, who were especially hurt by past discrimination and segregation, continue to lag behind. According to the Florida Housing Coalition, “Black families have the lowest homeownership rates in the state, and more than half of households are renters.” In 1970, two years after the passage of the national Fair Housing Act, the Black homeownership rate was 41%. It was up to just 43% following the 2008 Great Recession.

— Many Florida cities are zoned for only single-family homes. Duplexes and multi-family units that are less expensive are in short supply.

— Institutional investors are snapping up lower-priced homes and turning them into permanent rentals.

Florida is following California

The late Allen Morris, the longtime clerk to the Florida House and historian for the Florida Legislature, once told me that Florida was running 30 years behind California.

He was referring to population but also to the broader challenges of growth.

Admittedly, Florida is far from a carbon copy of California. For instance, we have fewer regulations and no state income tax. But when it comes to housing, the increasing similarities are worrisome.

Florida doesn’t want to become California when it comes to unaffordable housing and homeless encampments taking over downtowns.

In the last three years, California has lost 600,000 people, according to a column in Slate. One poll found that 4-in-10 Californians are thinking of leaving. And nearly 20,000 Los Angeles residents live in RVs, vans or cars — many of them workers, reported The Atlantic.

Florida, like California, has a supply problem — too few homes for a growing population. For instance, in 2017 Florida’s population grew by 350,000 but housing permits grew by less than 100,000, according to the Florida Policy Project think tank. Also, Floridians face rising home insurance prices, and some property insurance companies are pulling out.

But Florida differs from California in a positive way. The Sadowski Act, signed in 1992, was an incredibly creative and successful device to fund affordable housing through a classic public-private partnership.

The design was brilliant: As housing prices increase, so does revenue from the documentary stamp tax on mortgages and other transactions, which funds affordable housing programs.

Even better, the programs funded by the Sadowski Act have been remarkably successful, producing jobs and a return on investment of up to $6 of private investment for every dollar in tax revenue.

Because the private market is unwilling or unable to fund much affordable housing, the Sadowski Act has become a national model of effectiveness. The funds are used to support house and apartment construction, renovations and downpayment aid to first-time homeowners.

So it is doubly tragic that this model of effectiveness was diluted over almost 30 years by the Florida Legislature. “Sweep” is the polite word that is used to describe how the Legislature took some of the documentary tax funds intended for affordable housing and used it for other things.

Through the 2023-24 fiscal year, revenues provided by the Sadowski Act totaled $8.2 billion, says Mark Hendrickson, a facilitator for the Sadowski Coalition and executive director of the Florida Association of Local Housing Finance Authorities. But the Legislature grabbed $2.6 billion of it over the years. Put another way, for every $100 available for affordable housing, the Legislature took $32.

Let’s presume that other uses were legitimate; nevertheless, the affordable housing crisis hasn’t been a surprise. State leaders saw this coming and tried to provide revenue to deal with it. The State Housing Strategy in 1992 set the year 2010 as the goal for every Floridian to have “decent and affordable housing.” More than a decade after the finish line, we remain far from that ideal.

Each year, the sweeps were so wildly different that it was impossible for counties to plan. For instance, in 2012 and 2014, the Legislature took every penny of the Sadowski trust funds. That was right as construction trades and businesses related to homebuilding took a hard hit during the Great Recession, and they could have used all of the funds from the Sadowski Act.

I started writing about the raid of the Sadowski trust funds in 2010 as editorial page editor of The Florida Times-Union. In that year, $120 million had been raised by the trust funds but the Legislature was only going to use $30 million for affordable housing.

Two years ago — better late than never — the Legislature finally did the right thing and ended the raids. For the 2023-24 fiscal year, Duval County is receiving $11.8 million for affordable housing programs; St. Johns County: $3.4 million; Clay County: $2.6 million; and Nassau County: $1.1 million.

And more recent good news: Florida’s Live Local Act, which passed in the 2023 legislative session, goes even further with a serious attempt to deal with the housing crisis. It justifies a long look by local governments to determine how to implement the reforms, of which it includes a number that are long overdue, like:

— Tax benefits and incentives for building affordable housing.

— Statewide zoning reform allowing industrial and commercial plots to be used for affordable housing without going through the rezoning process.

Missing the big picture

Despite these recent positive developments, there are three big issues that many observers miss in the housing affordability crisis, says Jaimie Ross, who retired after leading the Thousand Friends of Florida and the Florida Housing Coalition. “People put in solutions before they understand the problem,” Ross told me in a phone interview.

- Density alone won’t solve the affordability crisis.

Many of the reforms being considered for affordable housing involve increasing density such as adding duplexes in single-family neighborhoods.

In a high-growth state, the pressure on prices will continue unless caps are placed on them. The free market is not working for affordable housing, Ross said.

“The main problem is that housing is priced at whatever the market will bear,” she said. “All you have to do is look at New York City. There are enough people with money who want to live there, so increasing density doesn’t solve the affordability problem.”

One solution, Ross says, is that houses built with tax funds need to remain affordable in perpetuity. A limit of 15 years or 30 years will only work if the housing market has caught up to demand, which has not happened.

For instance, Florida will lose 66,000 affordable housing units in the next 20 years as the caps on affordability expire.

- Incomes are lagging while housing prices are zooming.

Affordability is a simple equation: Income vs. housing cost. While housing costs have risen, average incomes have not kept pace, even with the minimum wage increasing in Florida.

- Housing is a major source of wealth for most families, which complicates reform.

While Americans consider food to be a basic need justified by food stamps, housing has not received the same acceptance. Vouchers for public housing are woefully short of demand.

Because housing is a major investment, homeowners have a strong incentive to support anything that increases home prices and oppose anything that threatens rising home prices. So there is an incentive for Not in My Neighborhood (NIMBY) movements.

One solution that is workable involves Community Land Trusts, a nonprofit that owns the land, then sells the house with a restriction on the resale price. Jacksonville has one, but it needs more funding.

A series of solutions must be used at the same time, Ross says. Take a big box employer that may receive property tax exemptions for locating in a city. How about using part of the large parcel for an affordable housing complex?

It is going to take city, state and federal action to address the affordable housing crisis. On a national level, the Affordable Housing Credit Improvement Act has 180 co-sponsors. It would finance nearly 2 million affordable rental units in the next 10 years, wrote Dennis Shea of the Bipartisan Policy Center in the Hill. It would boost the use of bonds for affordable housing as well as increase tax benefits for extremely low-income households.

The good news is that this issue is finally receiving attention. The bad news for Jacksonville is that we have yet to commit to a funding plan to address it. But that could soon change.

Next time: A look at Jacksonville’s affordable housing plans.

Lead image: The Florida Capitol | AP Photo, Phelan M. Ebenhack

Corrected: This column was updated on Oct. 3, 2023, to correct the percentage of Sadowski Act funding that the Legislature swept for other uses.

Mike Clark devoted about 47 years to Jacksonville's two daily newspapers. He retired in 2020 after 15 years as editorial page editor at The Florida Times-Union, where he and his staff won local, state, regional and national journalism awards.

He is the author of the new book, “Civil War Survivor: Incredible True Story of a Union Private.”