As Sandra Thompson listened to the freedoms that were demanded in the shadow of the Lincoln Memorial, the native Jaxson chuckled at the idea of some, rolled her eyes at the stilted progress of others and observed there was still work to be done.

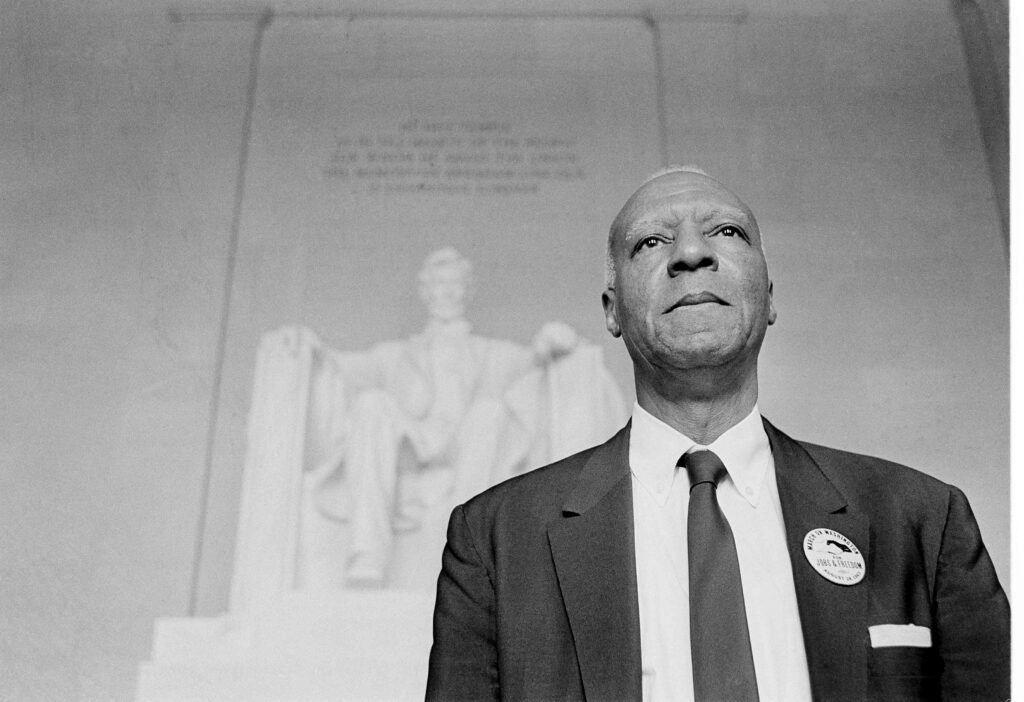

Monday marks 60 years since Thompson and about 200,000 others listened to labor leader and Northeast Florida native A. Philip Randolph, as well as Bayard Rustin and others call for changes from the federal government during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

Over the decades, the discourse surrounding the peaceful protest has focused more on freedom than jobs. Martin Luther King’s remarks there are remembered mostly for his vision for his children’s generation, but he also excoriated the country for foreclosing opportunities on Black Americans.

“We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation,” King said.

The Atlanta preacher may have taken the headlines – Thompson also recalls singer Mahalia Jackson set the tone for the day by calming down people’s spirits – but it was Jacksonville’s own A. Philip Randolph whose activism and mastery of mobilization helped make the march a reality.

For Thompson, attending the march was the next step in her activism. The year had been marked with bombings, wanton murders and children arrested for campaigning for racial equality throughout Southern cities. In Jacksonville, 1963 was the year Duval County Public Schools finally began to integrate. Nine years after the United States Supreme Court outlawed racial segregation in public schools, 13 Black students enrolled at five all-white elementary schools.

“You don’t think this is making history. It’s just something that’s happening,” remembers Thompson, who was 20 years old and weeks away from starting her senior year at Florida A&M University when she took a Greyhound bus to the capital city. “But it’s profound, you know, once you think, ‘I really heard this with my ears. I saw it with my own eyes, rather than in magazines or seeing it on TV.'”

From Crescent City to the capital city

Randolph was born in Crescent City in 1889, moved to Jacksonville as a toddler and graduated as valedictorian from The Cookman Institute in the Sugar Hill neighborhood in 1907.

By that time the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom began, Randolph, at 74, was the grand old man of the Civil Rights Movement. Hours before the march, W.E.B. DuBois – the scholar whose book The Souls of Black Folk inspired Randolph – died in Ghana at 95.

“Let the nation and the world know the meaning of our numbers,” Randolph said. “We are not a pressure group. We are not an organization or a group of organizations. We are not a mob. We are the advanced guard of a massive, moral revolution for jobs and freedom.”

Randolph, as was written in a 1943 pamphlet, was “pro-Negro but not anti-white nor anti-American.”

Florida Atlantic University Assistant Professor Candace Cunningham says Randolph’s work advocating for jobs and opportunities for Black Americans throughout the middle of the 20th century paved the way for the 1963 demonstration.

She says he knew the fight for civil rights was interconnected with the quest for economic freedom.

“These were never seen as separate issues,” Cunningham says. “If we look at the long Civil Rights Movement, from Reconstruction to the 1970s, … it’s never just, ‘We want this one thing,’ whether it is desegregation, social equality or whatever.’ There are always multipoint platforms. They are social equality, but they are also economic justice and educational opportunities.”

Black skin, diverse mindsets

Cunningham says the presence of both King and Randolph on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial was evidence that the Black community — neither then nor now — is a monolith. Randolph was a socialist who devoted decades to labor advancement.

“He’s a reminder at how complicated acquiring Black rights were,” Cunningham says. “You needed these people on either end of the spectrum. What people like A. Philip Randolph could do (was serve) on the margins of the more radical side. He could push some of these more moderate leaders to take up some of the causes in a more meaningful way. You needed those people, I think, on either side of the spectrum to push the movement forward.”

The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom was not Randolph’s first attempt at mobilizing American unions into shaming a president into positions that would lead to additional employment opportunities.

In 1941 he threatened a March on Washington to protest discrimination against African Americans in the defense industry as the country ramped up for World War II, which is credited for leading President Franklin Roosevelt to sign an Executive Order banning discrimination “against any worker because of race, creed, color or national origin” in June 1941. Later that decade, he encouraged Black Americans to refuse conscription into the military, which helped spur President Harry Truman to desegregate the military in July 1948.

Jobs and Freedom

Jacksonville historian and activist Rodney Hurst says Randolph was able to pressure presidents and produce change because of his role as a union leader.

His efforts started in 1925 when a collection of employees with the Pullman Company asked him to lead a nascent union. The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was initially not recognized by the American Federation of Labor, but eventually became one of the largest and most influential Black unions in the 20th century.

Labor unions played a pivotal role in attracting more than 200,000 people to Washington D.C. decades later.

One speaker, United Auto Workers President Walter Reuther, said that when all Americans had access to jobs it would produce equity in education, housing and public accommodations.

“Because if we fail, the vacuum of our failure will be filled by the apostles of hatred, who will search in the dark of the night and reason will yield to riots, and brotherhood will yield to bitterness and bloodshed. And we will tear asunder the fabric of American democracy,” he predicted.

Today, local and national labor leaders agree that the way to stabilize the world’s oldest democracy is building an economy where people — from all backgrounds — have access to employment and are paid enough to provide for themselves.

“What I think A. Philip Randolph did for the American labor movement was make clear that we are not going to win economic justice and create good jobs unless we tackle winning racial justice and freedom for all,” says SEIU President Mary Kay Henry. “He linked it in people’s economic security, so workers of every race could understand why the fight for racial justice was a fight that we all had to have if we all want to have good jobs.”

Henry adds that the American economy was built off the backs of Black and enslaved people.

“Just as our election maps and voting laws were created to silence people of color, our labor laws were written to avoid giving Black and brown and immigrant workers equal rights and protections. That’s why cross-racial solidarity is so critical in being able to create the sort of fundamental change that was won in the Civil Rights Movement.”

Local and national labor leaders say the demands of civil rights leaders in 1963 – particularly the need for career and workforce training to defeat unemployment and automation as well as an increase in the minimum wage – are labor fights that continue to be waged today.

“If the unions grow, the general wages, benefits and conditions are going to grow and survive as well, because you have a large group of people working together to make that happen,” says North Florida Central Labor Council President Russell Harper, whose organization is comprised of nearly a dozen unions in the region. “As one of the past managers of the (Local International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers) used to say: ‘We don’t care if y’all own yachts. But, let us have a small fishing boat, time to use it and money to afford gas to put in it. We want our piece of it. We want to be able to live, survive and get better.”

Harper graduated from Jacksonville’s Wolfson High School and has served as an active union member for 48 years. He says corporate interests have tried to separate workers along race, gender, sexual orientation and wedge issues.

“If they keep them apart and fighting each other, they can’t accomplish anything,” says Harper, whose organization represents 23,000 union members in Duval, Clay, Nassau, St. Johns and Baker counties. “That’s why the union movement and the Civil Rights (Movement) were so intertwined. It was all about the workers. It wasn’t about gender or anything else.”

The 71% of Americans who approved of labor unions last year equaled the highest percentage since 1965, according to Gallup, and has increased in each of the last six years from 56% in 2016.

Harper says union membership fluctuates, but it currently is at one of its highest levels in the last decade.

Despite public opinion on unions’ side, In Northeast Florida, unions and guilds have faced headwinds in their collective bargaining attempts over the last 18 months:

- Last year, Starbucks stores in San Marco and Mandarin voted to unionize and join Starbucks Workers United, but the coffee corporation has yet to recognize the union

- In June, members of the Brotherhood of Maintenance of Way Employees Division filed suit in federal court against Jacksonville-based railroad Genesee & Wyoming after 31 people were fired in May following a unionization effort earlier this year

- The Florida Times-Union NewsGuild went on strike in June to protest its membership going five years without a pay increase and its corporate ownership, Gannett Corp., reducing its benefits package.

- In July, a state law went into effect that stripped local government employees from having union dues automatically deducted from their paychecks and mandated that public unions have at least 60% of its members pay dues.

Harper believes the new law (SB 256) will embolden the Florida Legislature to target private sector unions.

“They see unions as the main opposition to them getting pretty much free rein to do whatever they want,” Russell says. “Workers are not going to put up with that. So, they decided to destroy the unions by making it hard to get the members to pay dues.”

Marching toward today

Harper, like Thompson, acknowledges there have been advancements over the last 60 years.

After she graduated from FAMU in 1964, she returned to Jacksonville to work as a teacher at Stanton High School where one of her peers on the faculty was Rutledge Pearson, for whom an elementary school is named today.

“There weren’t many jobs we could get back in the day. So, the unions were keeping you together,” says Thompson, who spent 42 years as an educator and working with children. “In the afternoons, after school, we would come Downtown and march. I never forget marching before City Hall.”

A year before he died, Pearson left his teaching position and worked with the Laundry, Dry Cleaners and Dye House Workers International Union, Local No. 218.

Thompson acknowledges that today, there are far more employment opportunities for Black men and women. When Randolph organized the march, it was focused mostly on men.

And while most of us see the March on Washington in the black and white of an old television, Thompson remembers it in vivid color, from her vantage point on the right side of the reflection pool on that hot August afternoon 60 years ago.

“What really astonished me is that (so) many people were there,” Thompson says. “And, it was so quiet. You would think that you have a lot of people and there would be a lot of noise. But, it was not. It was quiet. …It was a solemn occasion. People were not just having fun out there. The people who were there had a purpose for being there.”