When Meredith Tartaglia’s husband, an officer in the Navy, got his assignment at NAS Jacksonville, she went into action trying to figure where their four kids would go to school. The district’s military liaison assured her the kids could get into magnet schools, by and large the best rated schools in the district.

“My husband’s job is very demanding and he needs to be available at a moment’s notice, but he also wants to be home to see the kids,” Tartaglia says. “We chose to live on base because we knew we could get them into a good school [and] we could have transportation.”

But using the district’s transportation to those magnet schools comes with its own challenges: Her high schooler must wake up at 5:45 a.m. to get ready to catch the bus to Stanton College Preparatory School and regularly gets home after 5:30 p.m., Tartaglia says. Her child at James Weldon Johnson College Preparatory Middle School sometimes had no bus driver last fall amidst a districtwide driver shortage.

Still, she says it’s worth it, and driving around to take all four kids to school herself would take half the day. But families like hers might be faced with that reality in the coming years as the district looks to downsize its transportation budget.

Before anything that happens within school walls, the Duval school district spends about $63 million per year on transporting students there — that’s about 66% more than other large Florida school districts, according to the district. (The average annual price tag to get one child to a neighborhood school is $1,125. The average cost to take a magnet student to school is $2,165 because they typically travel further.) And as two of the district’s bus company contracts are coming up for negotiation later this year, Chief of Operations Paul Soares recently told the School Board that could drive prices up even higher.

In the short run, to cut costs. Duval Schools is combining school bus routes for GRASP Academy and Fort Caroline Middle School of the Arts, both in Arlington, and considering a policy change to make it easier to cut magnet school routes with low ridership. And more drastic changes to school transportation could be on the horizon. Former Superintendent Diana Greene told the School Board in April, “We have to come have this tough conversation. I’m sorry, but we will not survive if we continue at this rate.”

Soares presented 10 cost-cutting options to the Board during that same meeting, ranging from combining stops to cutting magnet school transportation altogether — with a potential savings of up to $18 million. It’s money the district says “could be used to support instruction in schools but instead funds school bus operations.” The state only pays for about a third of the district’s bus costs, so more than $40 million comes from local coffers each year.

Any drastic changes wouldn’t take effect for at least another couple years, and according to the school district, “Most of the more aggressive cost cutting strategies are for future discussion.” But the question is among the lingering challenges facing the next superintendent, as the School Board searches for Greene’s successor.

The district’s transportation budget has been a contentious issue in the past too: One former superintendent cut magnet school transportation in 2009 and the next superintendent reversed his decision. Decades before that, comprehensive magnet transportation was a key component of Duval Schools’ court-ordered desegregation effort.

For some School Board members, the idea of cutting magnet school busing also raises concerns about whether parents will leave the district-run schools altogether, amidst rising competition with charter and private schools — with private education easier to afford under Florida’s newly expanded school voucher system.

A few changes this school year

In the immediate future, starting this fall, students at GRASP Academy in Arlington may face longer commute times. The district is planning to combine the district-wide bus stops to the magnet high school with the bus stops for Fort Caroline Middle School for the Arts. The schools are about 1.2 miles apart.

Both of the magnet schools already use “express stops” — bus stops in public locations or at neighborhood schools — instead of smaller neighborhood stops. That’s largely because, unlike standard neighborhood schools, magnet schools serve kids from all over the sprawling county.

Combining the express stops for Fort Caroline Middle School and GRASP Academy will save the district $500,000 and have little impact on service, according to Soares.

The district is also recommending a School Board policy change to cut routes with less than 10 students. Currently, the policy allows cutting routes with less than five students. That change would also save the district about $500,000.

If the board approves that change, it wouldn’t affect students until a year from this fall. “We would send the letters out during the 2024 school year notifying people, and the first actual reductions wouldn’t occur until August 2024,” Soares told the School Board.

Together, the two small changes will save up to $1.2 million, according to district calculations. But that’s a small dent, which will likely get gobbled back up as the district’s transportation costs are expected to increase between $3 million and $6 million with upcoming transportation contract negotiations this fall.

Bigger changes on the horizon

In the long run, and likely under the leadership of the next superintendent, more drastic measures could be on the table. Some other possibilities up for consideration include:

- Changing school bus eligibility to students who live more than 2 miles from school (currently, students living more than 1.5 miles from school are covered) and lengthening acceptable walking distance to the nearest bus stop from 1 mile to 1.5 miles, with a potential savings of $500,000 to $1 million. The longer distances are the threshold under state law, but Duval’s current policy gives more students bus eligibility.

- Creating “super express routes” for dedicated magnet middle and high schools, with fewer bus stops, and encouraging students to use city buses or parental transport to the nearest stop. The change has a potential savings of $1 million to $1.5 million. (A dedicated magnet only has magnet students, like Douglas Anderson School of the Arts. Some magnet schools have both a traditional track and a magnet track).

- Creating magnet middle and high school transportation zones, so only students in certain neighborhoods near the school would get transportation and others would have to self-transport, with a potential cost savings of $2.9 million- $4.3 million.

- Only providing transportation to neighborhood schools, and students who choose a magnet school would have to self-transport, with a potential savings of up to $200,000 for cutting just elementary magnet school transportation, and up to $16 million for cutting just middle and high magnet school transportation.

Jacksonville Transportation Authority city buses are a potential alternative for students without district transportation to magnet schools. JTA has offered free transportation to Duval Schools students since last year.

But for some parents like Jennifer Tyler, whose 13-year-old child takes a bus to James Weldon Johnson, they’re not a viable option.

“There’s no way I would leave my 13-year-old daughter at some random city bus stop,” Tyler tells Jacksonville Today. She says she’d consider homeschooling “if that was my last resort, and I can keep her on the same type of academic track. I probably would before I’d put her on city buses.”

Soares acknowledged that while the free city buses could help cut district transportation costs, School Board members should keep in mind they “don’t have all the safety gear and equipment we have,” like crossing arms.

Transportation slashed before

Parental backlash to busing cuts are not new, nor are proposals to slash magnet transportation. In 2009 and 2011, then-superintendent Ed Pratt-Dannals cut transportation using some of the measures back on the table now.

In 2009, the district changed school bus eligibility to students who lived 2 miles away, lengthened acceptable walking distance from bus stops to 1.5 miles and cut some magnet school bus stops, saving about $4.8 million. Two years later, the district eliminated transportation to seven dedicated magnets, with a plan to phase out transportation to other magnet schools.

But by 2013, then-Superintendent Nikkolai Vitti reversed Pratt-Dannals’ decision and put $4 million back in the budget to revive magnet transportation. He said the move was in response to “high demand by parents,” according to The Florida Times-Union.

“For those who are here who remember, not a great time, and obviously everyone was happy to get back,” Soares told the School Board this year. “But now we’re revisiting it again because of the cost to do this.”

Magnet transportation key to desegregation efforts

Proposed magnet transportation cuts evoke the county’s troubled history with desegregation. After the district failed to comply with the mandate of Brown v. Board of Education in the 1960s, a local 1971 case resulted in court-ordered desegregation.

The local NAACP then sued in the mid-1980s alleging the district actually increased racial segregation in schools. Federal judges agreed, and Duval was ordered to perform a range of measures to desegregate schools and placed under court supervision.

One of the measures: “guarantee free transportation to students attending magnet programs outside their zones,” alongside developing specialized magnet programs. As the courts described the agreement, “The magnet programs were designed to attract a sufficient number of ‘opposite race students’ from the community at large to integrate the enrollment of those schools in racially imbalanced zones.”

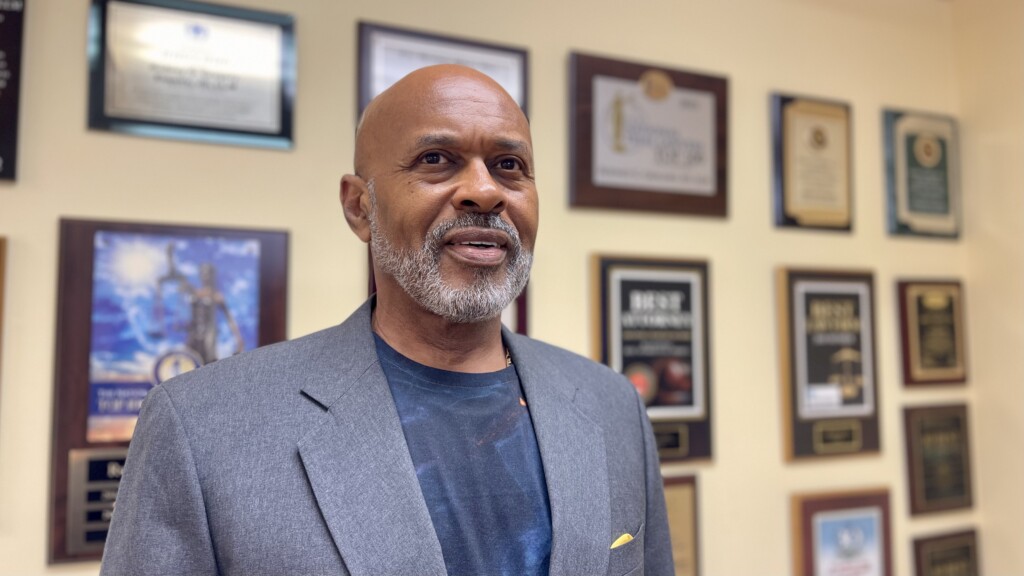

Rodney Gregory, who represented the NAACP in court, says transportation was an essential part of the civil-rights organization’s desegregation strategy.

“The question was: How do you get the kids there? … [Do you] force white parents to drive their kids to Black schools?” Gregory says. “It just went back and forth like that, so that’s why we had to have numerous discussions to try to find something which was somewhat in the middle, that was race-neutral, that would empower where we needed to go.”

He says the same argument circulating today — the high cost of transportation — is a new iteration of the argument he heard from the district in court three decades ago.

“When you look at cutting costs, don’t cut costs for what is working well for the betterment of our children,” Gregory says.

School Board member Warren Jones brought up similar concerns during a discussion about the proposed changes this spring, noting at least four of the recommendations could reduce diversity in schools. And for some schools, grant funding is linked to providing transportation, according to the district’s pros and cons list for different transportation options.

Federal courts lifted the court supervision of Duval Schools’ desegregation efforts in 2001, so the district is no longer required to provide free magnet transportation like it was beforehand.

The court agreed with the School Board, “attributing present racial imbalances in some schools to demographic factors beyond the Board’s control,” and lifted court supervision. But the NAACP disagreed, saying Duval Schools did the bare minimum to attract parents to magnet schools, and did not take additional steps to combat segregation.

Circuit Judge Rosemary Barkett wrote a dissenting opinion that said, “The record shows that the Board did not eliminate the vestiges of segregation at its formerly de jure [legally recognized] Black schools.”

School choice questions

Some School Board members have also questioned whether cutting transportation would save the district money in the long run — if it leads parents to leave district-run schools.

Terri Cripps decided to put her son in the magnet program at James Weldon Johnson Middle School, in part, because of bullying. She says her neighborhood school wouldn’t be a fallback option if she didn’t have a bus to the magnet school.

“There’s nothing at the neighborhood school level that makes me feel comfortable that he is going to be able to learn comfortably without the bullying issues,” Cripps says.

The district’s budget depends on student enrollment. Between state and local funding, Duval Schools will receive about $8,400 per student for the upcoming school year (that’s about a 4% increase from last school year). If a student opts to attend a charter school, that public funding flows to the business or nonprofit that runs the charter school instead of the district. Similarly, when students transfer to private schools or home school, public funding drops.

“I don’t know that it’s an accurate assumption to say that if we eliminate transportation to magnet schools, people go to their neighborhood school,” School Board Vice Chair Cindy Pearson said in April. “Not that there’s anything wrong with their neighborhood school, but we have all this choice, and people are making choices.”

One of those choices: private school with expanded state funding. A new Florida law, HB 1, removed financial eligibility restrictions and enrollment caps from a state scholarship program, commonly called vouchers, to pay for private school. According to the Department of Education, the average scholarship was $7,700 per student last year. The state already offered a $750 transportation scholarship for parents who want to send their children to a public school they’re not zoned for.

Cripps says if she lost magnet transportation, she’d probably choose the county’s online “virtual school” for her son. Another parent, Bridgette McKeithan, says she’d switch her daughter to a charter school before considering her neighborhood middle school in Mandarin.

“My daughter most likely will not be able to go to the magnet school if they get rid of the busing from our neighborhood,” McKeithan says. “I would definitely not consider the local neighborhood middle school and put her back in the charter school.”

This article is part of Jacksonville Today’s superintendent search series looking at big issues the district’s next superintendent will face. What do you think is the most pressing challenge facing Duval County Public Schools? Email reporter Claire Heddles at claire@jaxtoday.org.