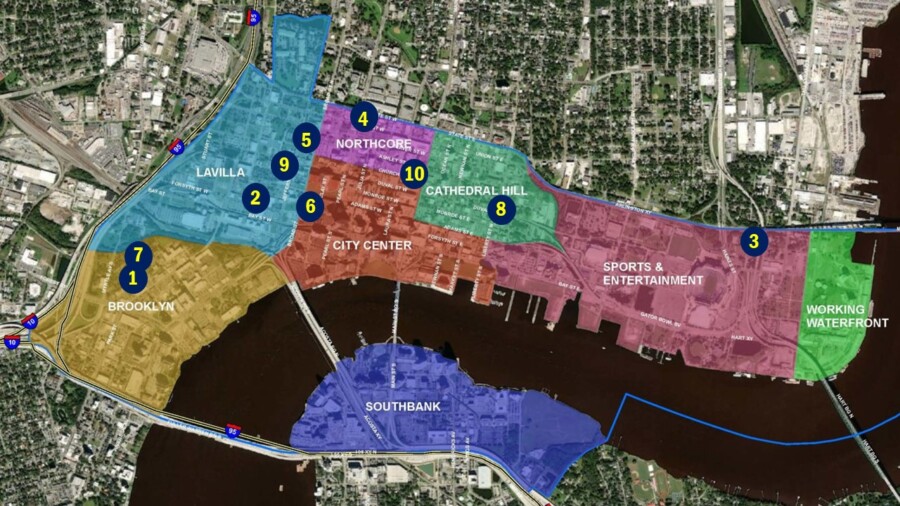

In honor of National Historic Preservation Month, here’s a brief list of overlooked buildings, structures and landmarks in Downtown Jacksonville that could end up being demolished if more attention isn’t given to their historical significance.

1. The last post-Civil War cottage, Brooklyn

328 Chelsea St.

Jacksonville during the Civil War was a hotbed of Union sentiment, with many white citizens and virtually all African-Americans supporting the U.S. cause. The Union occupied Jacksonville four times and held the town permanently after the last occupation in February 1864. A large portion of the Union’s soldiers were formerly enslaved who joined up to fight the Confederacy in order to secure freedom for their loved ones. After the end of the war, many veterans and their families stuck around and established Jacksonville’s earliest Black neighborhoods. One of these was located in the northwest portion of Brooklyn, which grew into a sizable Reconstruction-era Black community.

There’s no record of who built the house at 328 Chelsea St., but it predates the 1868 plat of the neighborhood, a fact that can be seen even today, as the front of the house juts out toward the street. This makes the house one of the few buildings providing a direct link with Jacksonville’s Reconstruction-era past. The house is sometimes known as the Buffalo Soldier House, although this is anachronistic, as it would predate the establishment of all-Black “buffalo soldier” regiments who served in the Indian Wars.

The historic home, like most of the older buildings still standing in Brooklyn, are in danger of demolition. Failing in its 2013 request to become recognized as a local historic district, much of the storied Gullah Geechee neighborhood has been erased from existence with the recent emergence of Brooklyn as a popular location for urban living. With gentrification in full effect, this boarded up and abandoned post-Civil War cottage is the last still standing.

2. Old bordello, LaVilla

801 W. Forsyth St.

A hundred-twenty years ago, Houston Street, then named Ward Street, was the epicenter of Jacksonville’s bustling red light district. The district originated in early 1887 as a result of Jacksonville Mayor John Q. Burbridge’s chasing most of Jacksonville’s prostitutes over the city line into the suburb of LaVilla. Burbridge’s efforts were thwarted when Jacksonville annexed LaVilla a few months later on May 31, 1887. After the January 1897 opening of Henry Flagler’s Jacksonville Terminal Co. passenger railroad depot, the red light district grew rapidly and ultimately became known as “The Line.”

By the early 20th century, the Line had more than 60 bordellos concentrated along four blocks of Ward Street between Lee and Bridge streets. Also home to a large number of saloons and gambling houses, the Line was recognized as a dangerous place full of drunkenness, crime and harsh living. The Line existed until the criminalization of prostitution in the early 20th century. Following several attempts to erase this colorful element of local history, most of the structures associated with the red light district have been demolished over the past 50 years. The structure at 801 W. Forsyth St. may be the last surviving bordello in the district. Public directories and Sanborn maps indicate the building once housed a red light district saloon that was owned and operated by Black businessman and bordello owner George Stevens.

3. Fairfield Public School, Downtown

515 Victoria St.

Fairfield, one of urban Jacksonville’s oldest communities, was largely located beneath the Mathews Bridge. Fairfield’s beginnings came in the late 1860s when New Yorker Jacob S. Parker acquired over 150 acres along the St. Johns River. Soon, Parker helped establish the second paved road and first toll facility in Duval County through the area. A few years later in 1876, Parker established Jacksonville’s first fairgrounds on the northernmost portion of his property, a situation made possible in part because Parker was the manager of the first Florida State Fair.

The fair’s popularity sparked Parker’s further interest in real estate, which resulted in his naming the surrounding area “Fairfield.” In 1880, the community was incorporated as a town and Parker was elected as the first mayor. In 1887, with a population of 543 residents, the city of Fairfield was annexed into Jacksonville.

The old Fairfield Public School is one of the largest buildings from the neighborhood’s heyday that survives. Completed in 1919 on a parcel now bounded by two expressways, the building is seldom used.

4. Fraternal Order of Odd Fellows Hall, Downtown

330 W. State St.

The Fraternal Order of Odd Fellows is one of many currently unprotected buildings Downtown worthy of a local landmark designation. According to James Weldon Johnson, the Odd Fellows lodges were made up of white collar workers, in contrast to the Masonic lodges, which recruited largely from stevedores, hod carriers, lumber mill workers and brickyard hands. Located at the southeast corner of State and Cedar (now Pearl) streets, the Odd Fellows Hall was designed as a three-level building with retail on the ground floor.

Built right after the Great Fire of 1901, this is where the Cookman Institute held its graduation ceremony in 1907. A young A. Philip Randolph, the class valedictorian, gave a speech he called “The Man of the Hour.” Randolph would later organize the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, the first predominantly African-American labor union, as well as the March on Washington in 1963. In March 1912, Booker T. Washington, co-founder of the National Negro Business League and key proponent of African-American businesses, visited Jacksonville as a part of his Florida tour. The Odd Fellows Hall hosted a banquet held for him after he arrived in town by special train. In later years, Zora Neale Hurston also performed at the Fraternal Order of Odd Fellows.

In later years, it was the location of a Green Book site, the Sunrise Restaurant. The restaurant was located inside George D. Wood’s Independent Furniture Company store on the ground floor of the Fraternal Order of Odd Fellows Hall. Wood was the president of the Mount Olive Cemetery Association and owner of the furniture store and the Durkeeville Apartments.

Currently vacant, in recent years this building was occupied by River Region Human Services Inc. but is now in danger of demolition.

5. Genovar’s Hall, LaVilla

644 W. Ashley St.

This building was constructed by Sebastian Genovar in 1895. It originally housed his grocery business. During the early 20th century, this three-story structure housed a variety of businesses during the formative years of ragtime, jazz and blues genres in LaVilla. In 1931, the Wynn Hotel opened in the building’s upper floors, while a jazz club called the Lenape Tavern and Bar opened on the first floor.

Operated by Jack D. Wynn, the hotel became a favorite spot of Louis Armstrong when visiting LaVilla. In addition to Armstrong, others who performed at the Lenape include Dizzy Gillespie, Billie Holiday, James Brown, Louis Jordan and Ray Charles, who briefly lived one block south on West Church Street. Since the 1990s River City Renaissance urban renewal program, the property has been owned by the City of Jacksonville, although past attempts to restore it haven’t found success.

6. JoAnn’s Chili Bordello, Downtown

521 W. Forsyth St.

This small commercial storefront opened in 1906 and was briefly used as a real estate office and bicycle shop. In 1910, it was purchased by Charles Sumner, who used it as a market for a dairy business passed down from his father, called the William P. Sumner Company.

In 1910, Sumner added a narrow four-story building in the rear of the property. Sumner, whose previous location had been destroyed by the Great Fire of 1901, built his new dairy operation with brick and reinforced concrete, making it fireproof. During the 1920s, it was used as an ice cream factory for the J.R. Berrier Ice Cream Co. In 1961, Berrier’s Ice Cream became the focal point of an NAACP boycott.

Eventually, during the 1980’s, the building housed JoAnn’s Chili Bordello, a restaurant designed to look like a bordello, with waitresses dressed in corsets and garter belts. The restaurant’s motto was “17 varieties of chili served in an atmosphere of sin.”

7. Mount Calvary Baptist Church, Brooklyn

301 Spruce St.

Abandoned for more than 24 years, Mount Calvary Baptist Church is one of the largest buildings still standing in Brooklyn that date back to the neighborhood’s days before urban renewal and gentrification. It served the Brooklyn community until 1999, when the Rev. John Allen Newman relocated the congregation to a Northside location near Gateway Town Center.

Located at 301 Spruce St., the church was built in 1955 by James Edwards Hutchins and commissioned under the leadership of the Rev. William Hill. Born in Blakely, Georgia, in 1890, Hutchins was one of the few local Black contractors who designed buildings during segregation. In Black Jacksonville, Hutchins was responsible for several churches and residences in the College Gardens and Durkee Gardens subdivisions. After World War II, he worked with the Veterans Administration to train Black carpenters, brick masons and architects.

8. The Muller / Moody Residences, Downtown

403 Liberty St., 411 Liberty St., 411 E. Duval St.

Built shortly after the Great Fire of 1901, city directories show that 403 Liberty St. was originally the home of Janey Barbara Muller, widow of Gustav Muller, a German immigrant that came to Jacksonville around 1880. Between 1882 and 1893, Muller had a wholesale groceries, grain, liquor, and tobacco business on East Bay Street (Meyer and Muller). By 1895, he had a new partner and concentrated on wholesale liquors (Muller and Robertson), with their business located in the 300 block of East Bay Street, known as the Muller Block. Upon his death in 1897, Gustav Muller, Jr., continued the family business, which later became the G. Muller & Co., proprietors of the Jacksonville Steam Bottling Works, which expanded to soft drinks. In 1909, Janey and Gustav’s daughter, Ethel Dolores Muller, married prominent Jacksonville businessman Maxey Dell Moody in her mother’s house.

In 1915, neighboring 411 Liberty St. was built for Maxey Dell Moody and Ethel Muller. Moody was in the road-building construction equipment industry. His business, M.D. Moody & Sons, was formed in 1913, incorporated in 1946 and later expanded by his son Maxey Dell Moody Jr. into Moody Truck Center, Moody Light Equipment Rental, the Moody Machinery Corporation, Moody Fabrication and Machine, Dell Marine and MOBRO Marine, Inc., taking his contributions to the construction industry into the 21st century. While not all the businesses survive today, three do. Moody’s business once stood as the oldest family owned road equipment company in Florida. The Miami Herald credited Moody as the organizer of the American Road Buildings Association. Today, these Cathedral District residences and an adjacent related property at 411 E. Duval St., are owned by Duval Street Properties, LLC and are likely to be razed to pave way for a larger infill multifamily development project.

9. Safer family homes, LaVilla

316-322 Jefferson St.

316-318 and 320-322 Jefferson St. are two of the few remaining houses in LaVilla built immediately after the Great Fire of 1901. By 1914, the identical two family flats were occupied by members of the Safer family. Benjamin Safer was the first family member to arrive in Jacksonville from Lithuania around the turn of the century. Safer established the first kosher meat market in Jacksonville and was instrumental in forming the Orthodox Congregation B’nai Israel. B’nai Israel built a synagogue at the northwest corner of North Jefferson Street and West Duval Street, leading to this section of LaVilla’s becoming an early 20th century Jewish community.

Public directories indicate the block transitioned to Black community around 1933. The first Black tenants were employed as Pullman Porters at the train station and waiters and cooks at the nearby George Washington Hotel. Developed by Robert Kloeppel, the George Washington opened its doors on December 15, 1926, with Mayor John Alsop, Gov. John W. Martin and former Gov. Cary Hardee in attendance. At the time, the 13-story building was the largest and most magnificent hotel in the city and the nation’s first 100% air-conditioned hotel. Famed guests over the years included Charles Lindbergh in 1927 and the Beatles in 1964. Once owned by mobster William “Big Bill” Johnston, the hotel closed in 1971 and was razed and replaced by a surface parking lot in 1973. Today, the block is occupied by JEA’s new headquarters complex.

Surviving the city of Jacksonville’s River City Renaissance plan, which leveled most of the neighborhood, today 316-318 and 320-322 Jefferson St. live on as a reminder of the impressive residential architecture and density that once dominated the streets of LaVilla.

10. Universal-Marion Building, Downtown

21 W. Church St.

Until recently JEA’s headquarters, the Universal-Marion Building is a large mid-century building with a history many consider worth preserving. Designed by Ketchum & Sharp, the 268-foot tall, 19-story tower was the tallest building on the Northbank and second-tallest in the city when it was completed in 1963. It was also one of a handful of buildings in Florida to feature a revolving rooftop restaurant. The 250-seat Ember’s Restaurant was said to be the largest revolving restaurant in the world, rotating 360 degrees every 1.5 hours when it opened in 1964.

The complex also included a six-story, 180,000-square-foot J.B. Ivey & Co. department store and a parking garage that once included a Purcell’s women’s department store on the ground level. The building’s original premier tenant was founded by Louis Elwood Wolfson, whose firm co-financed the production of Mel Brooks’ movie The Producers, which won an Oscar and later became a major Broadway play. It also funded Woody Allen’s first movie, Take the Money and Run.

Recently completing a new headquarters a few blocks southwest, JEA intends to sell the Universal-Marion Building to new owners who could either reuse or raze the skyscraper. While the mid-century mixed-use office and big-box retail complex may not be of significant value to JEA, the building is an important part of Jacksonville’s urban landscape that’s worthy of being seriously considered for adaptive reuse as opposed to demolition.