Nick VanderWal was a retired cop in Florida who couldn’t let go of his unsolved cases even decades later — especially a 1992 rape by an armed burglar who tied up his victim and placed duct tape over her eyes during an attack so awful that judges later called it barbaric and cruel.

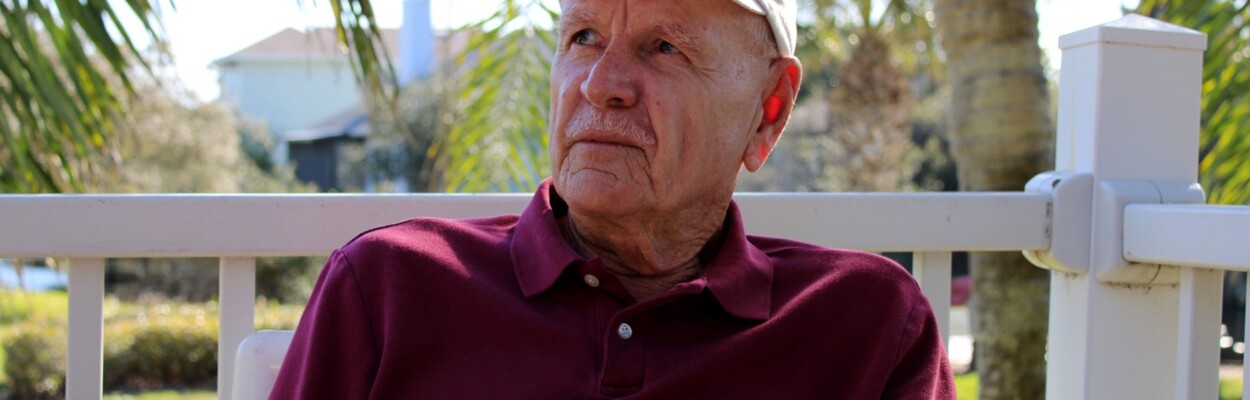

Twenty-three years after he retired from the police department in Atlantic Beach, VanderWal, now 76, is being lauded for his diligence and tenacity on behalf of a traumatized victim who had been denied justice for so long.

The full story of how the crime came to be solved only decades later — and VanderWal’s role in the case — is re-emerging from the files of a Florida appeals court, where judges recently spelled out the tale and called out VanderWal’s dedication to the victim. It comes amid a national conversation over incidents of horrific police misconduct, a reminder there are officers doing honorable work.

Fifteen years after he left the force, VanderWal was watching the news on his computer one morning when he heard reports about a serial rapist terrorizing communities near military bases along the East Coast. Atlantic Beach is only a few miles south from Naval Station Mayport.

He thought back to his own cold case files, paperwork he left behind in filing cabinets memorializing chilling conversations with victims. The 1992 rape he had investigated involved a young woman, then 25, forced to submit by a gunman she had seen earlier pedaling a beach-cruiser bicycle on a spring afternoon past her condominium wearing boat shoes, mirrored sunglasses, a baseball cap and a Hawaiian shirt.

Through the years, that case stood out to VanderWal. He remembered his encounter with the victim after she had freed herself and dialed 911 after the attack. She was seething, he said, “really mad about what had happened to her.” He personally took her to a doctor for her rape examination.

There had even been a serious misstep: At one point, just after the attack, VanderWal had arrested the wrong man for the crime. The victim said she didn’t recognize him from photos the detective showed her, and the Florida Department of Law Enforcement said the forensic evidence wasn’t a match. That man was exonerated.

Back at the police station, long after VanderWal retired, the 1992 case was deemed so old, so unsolvable, that someone in the department apparently threw out the detective’s notes — but not the rape-kit swabs in the sealed sexual-assault envelope kept in the refrigerated evidence room.

Seeing the news reports about the East Coast rapes, VanderWal wondered if they might be connected to his cold cases: “I just thought, well maybe this could be the break,” he said in a recent interview from his home.

VanderWal called his old boss and from his retirement recommended that the DNA evidence be resubmitted for testing, after a generation’s worth of improvements in the medical technology.

Months passed.

Then there was a match.

The suspect in the East Coast attacks wasn’t connected, after all. But VanderWal’s diligence turned up a connection to a construction worker, Kenneth Alfred Bicking III, now 62, who had been living in nearby Mayport while serving in the Navy at the time of the 1992 attack.

Bicking had a lengthy criminal record and was most notoriously accused of killing a former Dallas Cowboys punter and kicker, Colin Ridgway, in 1993. Police in Texas said they believed Bicking was hired to kill Ridgway by Bicking’s father and Ridgway’s widow, Joan Jackson, but prosecutors concluded they didn’t have enough evidence to convict anyone in the case.

Bicking also was arrested alongside William E. Wells III for breaking into a boat and stealing equipment. He was convicted in 1994 of the felony, according to court records. Wells, who also has a lengthy criminal background, was sentenced to life in prison in 2004 for killing five family members in Mayport and living with their corpses. Known as the “Mayport Monster,” Wells killed a fellow inmate in 2011, and he received the death penalty after killing another inmate in 2019.

Nineteen years after the Florida rape, the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office issued an arrest warrant for Bicking, who by then was living in North Lauderdale in South Florida, on felony charges of sexual assault, kidnapping and burglary.

Bicking’s victim, who declined in a recent interview to discuss the case, testified against him at his trial, in September 2014, along with VanerdWal and Bicking’s ex-wife, who said the couple had owned a beach-cruiser bicycle and a handgun like the one the victim saw. She also had been a key witness in the murder-for-hire investigation in Texas, saying Bicking had confessed to her that he had shot the player, but her testimony in that case was excluded as privileged.

“I started thinking that I’m going to remember every last detail of this person that I can if there is ever an opportunity to catch him if I made it through, and I didn’t want him to know that I could see, so I acted like I couldn’t, but I could see,” the victim said at Bicking’s trial.

“I knew he was going to rape me at that point when he took me upstairs,” she told jurors. “I knew it.”

Bicking himself testified in his case. Asked whether he raped the victim, he answered: “Absolutely not.” But he told a prosecutor that he must have had sex with her, probably in the back of his van around the time of the 1992 rape, based on the DNA evidence, even if he didn’t remember doing so.

The jury wasn’t convinced. It returned a verdict in 24 minutes, 22 years after the rape: Guilty. The judge sentenced Bicking to two life terms in a Florida prison.

From his prison cell in Crawfordville, just south of Tallahassee, Bicking declined to talk about the case except to call it a “nightmare.”

Bicking had appealed his life sentences to the 1st District Court of Appeals in Tallahassee, where a three-judge panel recently upheld them. Judges called Bicking’s testimony in his case “patently false” and agreed with the trial court’s finding that the crime was especially egregious and inflicted “permanent trauma and suffering on his victim.”

Judge Bradford L. Thomas even suggested sexual assault cases like Bicking’s should be eligible for the death penalty.

VanderWal said that he played only a small part in the case and that many others were involved. When he called to recommend the DNA be resubmitted, he was hoping there would be a match for three or four cases that were unsolved. The anger of the victim in the 1992 case stuck with him.

“Twenty years later she was still mad,” VanderWal said. “She got him convicted, and more power to her because she saved a lot of other people from a lot of grief.”

This story was produced by Fresh Take Florida, a news service of the University of Florida College of Journalism and Communications. The reporter can be reached at alexaherrera@freshtakeflorida.com. You can donate to support the students here.

9(MDEwNzczMDA2MDEzNTg3ODA1MTAzZjYxNg004))