Two years after his death, Henry Aaron was flung into Florida’s culture wars.

The iconic baseball player is the subject of a children’s book that recently became a rallying cry on social media over the claim it was “banned” by Duval County Public Schools. In reality, Matt Tavares’ 2011 book, Henry Aaron’s Dream, was one that the school district recently approved after a lengthy review to ensure all books comply with new state laws restricting how schools teach on topics of race, gender and sexuality. That review continues for all 1.6 million of the district’s titles.

Aaron, who was known for his courage under pressure and gentlemanly grace away from the diamond, proved a cultural lightning rod in the same city where, 70 years ago, he helped the Jacksonville Braves win the South Atlantic League title. He met his first wife in Durkeeville. Tavares’ biography mentions that Aaron and his two Black teammates on the Jacksonville Braves “…played their games in Southern cities where Black people and white people weren’t even allowed to play checkers together.”

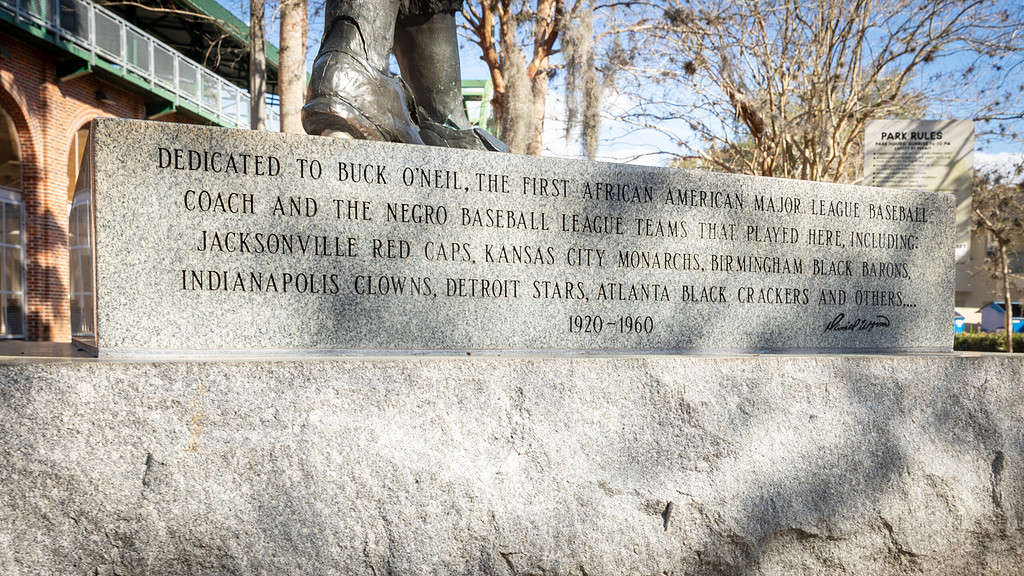

Alongside Aaron, scores of Black players, including James Weldon Johnson, played at the facility that was recently renamed Henry L. Aaron Field at J.P. Small Memorial Stadium. However, Black interest and participation in the game has waned locally over the decades amid the cultural rise of football and basketball — something that local Black baseball evangelists are trying to reverse.

Heritage and hustle

One of them is Darian Thomas, who grew up playing baseball in Jax, eventually at First Coast High School. Now In his early 30s, he recalls being one of the few Black players on youth baseball teams and having to overcome obstacles that were unrelated to his talent, like not having “parents being friends and… a lot of political aspects” of being a minority.

After graduating from Jacksonville State University in Alabama, he knew he wanted to coach. He also wanted to make an impact.

“When I came back home, I noticed that a lot of people pouring into football, a lot of people pouring into basketball, but a lot of Black people just kind of phased out of baseball because baseball is expensive or they face some kind of adversity that they don’t want to deal with — like coaches playing their sons,” says Thomas, who’s in his first year as head baseball coach at Raines High School.

Thomas was a middle school baseball coach for years before taking over the head position for a program that finished 5-15 last year.

Varsity baseball season began this week. But Raines played one of its most important games of the season on Feb. 15th: the High School Heritage Classic. The contest between Raines and Ribault high schools is a preseason game in name only. The Jacksonville Jumbo Shrimp, the Triple-A affiliate of the Miami Marlins, have staged the game each of the last four years between the two predominantly Black high schools to elevate and celebrate Jacksonville’s Black baseball history. The game is played at 121 Financial Ballpark during the middle of the school day so students from local elementary schools can attend on field trips.

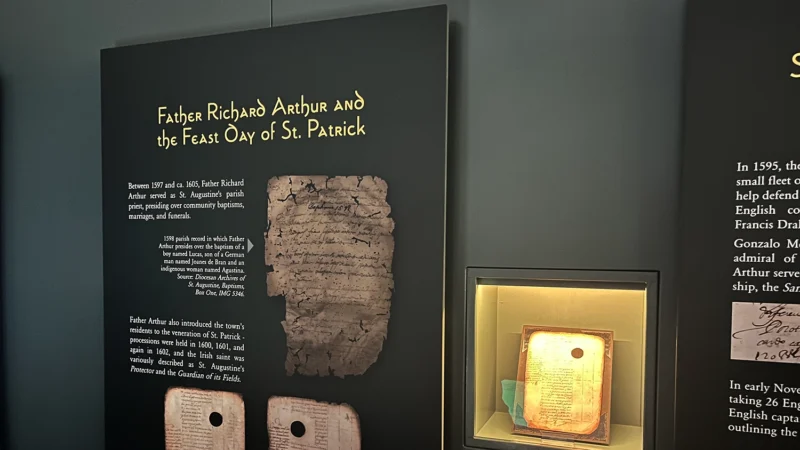

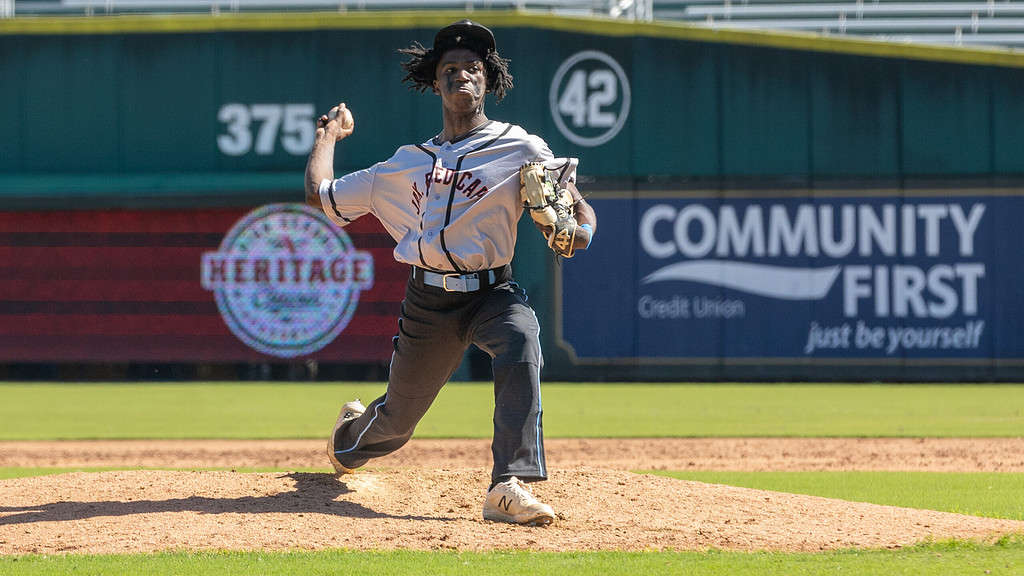

Raines and Ribault don the uniforms of the Jacksonville Red Caps, a Negro American League team that played at what was called Durkee Field in the late 1930s.

“I take this very seriously,” Ribault pitcher Tyree McKeiver says after the game. “I meant straight business.”

After Ribault’s 8-3 victory, McKeiver is standing a few steps away from home plate with a grin on his face. As his right shoulder is getting iced, the senior can’t stop smiling at being a high school pitcher who just stepped onto the mound at a professional field in front of 1,000 people.

“Me and that mound, that’s it. It’s my true passion,” McKeiver says. “That’s where I belong. I feel like I belong at pitcher. And, I’m going to keep striving at pitcher.”

McKeiver says his mother introduced him to baseball. She entered him into an array of sports, but he got better at baseball and got hooked. His goal is to play ball at Albany State.

He is bucking the trend, as the number of African Americans in baseball is declining nationwide. According to the Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport, 7.2% of Major League Baseball rosters on Opening Day in 2022 were African American, the lowest percentage since the Orlando-based institute began collecting data in 1991.

At the collegiate level the numbers are worse: only 3.9% of Division I baseball players at non-historically Black colleges and universities in the 2021 season were Black.

Longtime local broadcaster Frank Frangie founded the nonprofit Walk Off Charities in 2017 with the aim of introducing the game in urban and underserved communities through providing development opportunities, training coaches so they can teach the game and sponsoring youth baseball players.

Last week, Walk Off Charities hosted 12 high school programs in its High School Baseball Classic showcase at San Souci Baseball Park, with proceeds going to the Walk Off Jax RBI Spring League.

Walk Off, through a partnership with MLB’s Reviving Baseball in Inner Cities program, and an affiliation with Cal Ripken Baseball — a national youth baseball organization — will outfit nearly 500 players at 10 Jacksonville parks in areas like Brentwood, Grand Park, Sans Souci and the Westside.

Jarrod Simmons, Walk Off’s director of operations, says the organization provides the uniforms and equipment, pays the umpires and handles game scheduling.

“We do have a focus on African American kids,” Simmons says. “A part of the reason the charity was founded was (that) in Frank’s eyes, he grew up playing and watching baseball in the 60s and 70s. Most of the top players were African American players. They were MVPs, Rookie of the Years and stolen-base leaders. Looking back then compared to now, roughly 25% of the league was African American. Now, it’s 7%.”

Darryl Owens believes a solution is getting more coaches in more public parks to spread the gospel of the game. Owens recalls learning baseball skills from Hank Aaron himself in Lincoln Estates when he was a child. Aaron taught the game in a way that made Owens want to continue in the sport.

“As kids, it’s like meeting Superman or Batman,” Owens recalls. “We went crazy. And, then once we all calmed down, he was like, ‘Let me show you some drills for hitting.’”

Owens taught what he learned to his grandson, Eric Turner, a freshman outfielder at Ribault.

“Now, he loves it, and he caught baseball fever,” Owens says beside the Trojans’ dugout during the Heritage Classic. “And, that’s all you have to do is show them. They’ll catch it. …He’s out here. And, I’m out here to support him — and all the kids.”

Welcoming fresh faces to the diamond

Introducing Black boys and Black girls to the diamond is one thing. Ensuring they stick with the game long enough to get good at it is another.

That’s what Takeilia Clarke is committed to doing for her kids. Her son Braylin is a sophomore outfielder at Ribault. Braylin’s twin sister, Brayla, is the shortstop for Ribault’s softball team.

Clarke applauds the Jumbo Shrimp for their outreach in urban areas and for holding the Heritage Classic. She says more can and should be done at the amateur level in order for Black boys to feel accepted playing baseball.

When the Clarke family moved to Jacksonville from Georgia, she signed Braylin up to play at Dinsmore Park in Northwest Jacksonville. He was initially placed on a developmental team.

“When he first started, the coaches didn’t want him to play,” Clarke recalls. “When they realized he could play? Oh, now you want him on your team?”

Exposing children to the opportunities in the game — on and off the field — has been a passion of Jumbo Shrimp General Manager Harold Craw since he arrived in Northeast Florida ahead of the 2016 season.

Craw is believed to be one of the few Black general managers in affiliated baseball.

Last year, Minor League Baseball launched an initiative to celebrate the impact Black players made in the game. Through the effort — dubbed “The Nine” because that was the number Jackie Robinson wore during his year in the minor leagues — teams encouraged baseball development in underserved areas, connected with nearby HBCUs and provided mentorship and internship opportunities.

All of those were things the Shrimp have done for years.

For the past five years, Craw has quietly worked with students at Andrew Jackson High School who have expressed an interest in sports management. He says last week’s Heritage Classic represented “a huge opportunity for us to share the history of baseball in our great city, while at the same time allowing two high schools an opportunity to play on a professional field.”

Last week, during an appearance on First Coast Connect with Melissa Ross, Craw told a story about working with former National League Rookie of the Year and two-time All-Star Vince Coleman — before Craw arrived in Jacksonville — and not realizing Coleman was a Raines graduate.

John Henry “Pop” Lloyd spent a portion of his childhood in Jacksonville after being born in poverty in Palatka. Lloyd and Honus Wagner were considered two of the best shortstops in the early 20th century. Lloyd was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1977.

“We have a rich history,” Craw says. “We have one of five ballparks that are still functioning (and) on the historical registry as a historic ballpark in our J.P. Small Ballpark…the history of baseball in our town dates back so long ago. I’m continuing to learn about some of the talent that has been here. …every year I learn new things about our area and the folks who have played here.”

Thomas, the Raines High baseball coach, says with the park renamed after Aaron and longtime Stanton High School Coach James Small, today’s players have a tangible reminder of the game’s long legacy here.

“Being a baseball player growing up, I would tell people I played baseball. They would say ‘Oh, that’s a white sport,’” Thomas says. “Baseball is the only sport that has had a league specifically for people of color. So, I don’t know how you could say it’s a white sport when we, actually, had a league specifically for us.”