Five decades before the Pilgrims celebrated their feast at Plymouth, Massachusetts, French and Spanish colonists held feasts of celebration on Florida’s First Coast.

Origins of Thanksgiving

Thanksgiving has its roots in European traditions. All across Europe, it was customary to give thanks to God after the yearly harvest and other important events. In the age of colonization, it became customary for expeditions to give thanks after completing a successful voyage. The American celebration of Thanksgiving has its roots in celebrations held by English settlers in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1610 and in Plymouth, Massachusetts, in 1621, but the tradition is far older.

In the Americas, the tradition of celebrating Thanksgiving at the completion of a long journey goes all the way back to Christopher Columbus’s first voyage across the Atlantic in 1492. On Sept. 25th of that year, Martin Alonzo, captain of the Pinta, reported that he spotted land. Columbus “fell on his knees and returned thanks to God, and Martin Alonzo with his crew repeated, “Gloria in excelsis Deo.” It turned out that what Alonzo saw was just a cloud; the expedition wouldn’t reach land until Oct. 12th.

Possibly the first known words of Thanksgiving said by a European in what’s now the continental United States came from Juan Ponce de León. When his expedition spotted the East Coast of Florida in 1513, Ponce de León said, “Thanks be to Thee, O Lord, who has permitted me to see something new.” Several later conquistadors are recorded as saying words of thanks and holding ceremonies of Thanksgiving in Florida and elsewhere.

Thanksgiving at Fort Caroline

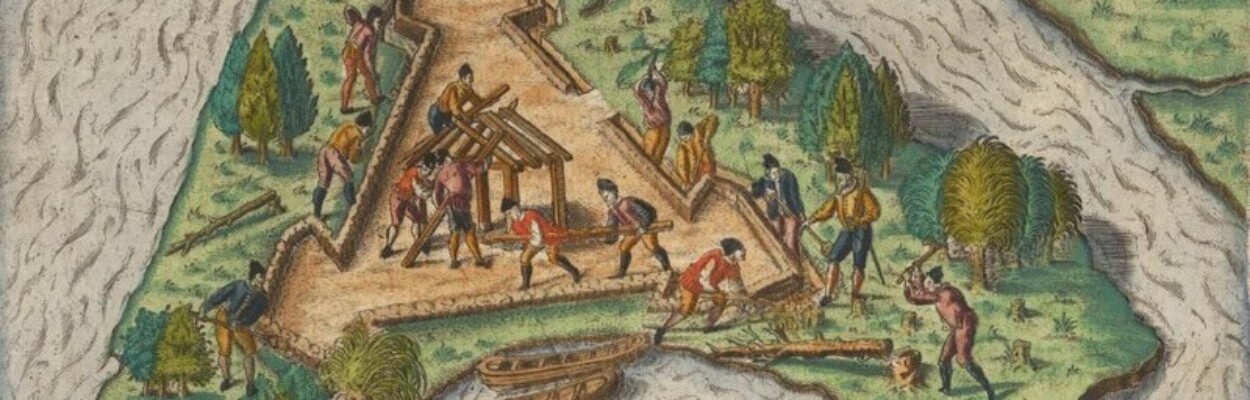

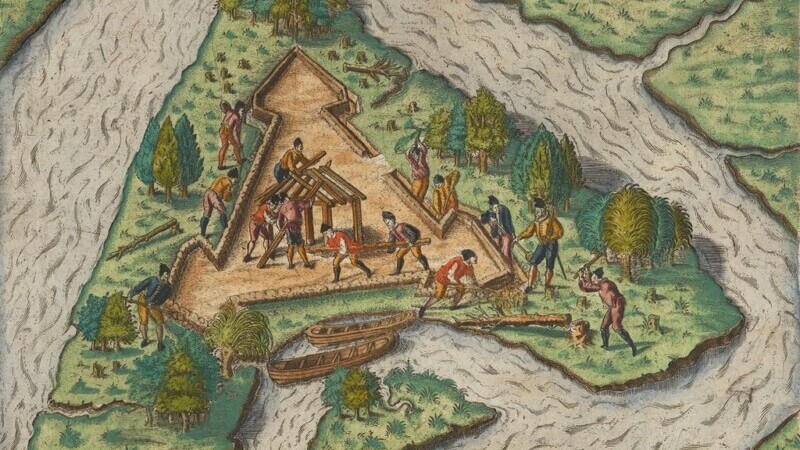

In 1564, French colonists under René Goulaine de Laudonnière sailed into the St. Johns River, which they called the River of May. Their goal was to find a suitable place to build a new settlement to serve as a haven for the Huguenots — a French Protestant sect — and claim Florida for France. On June 29th, they chose a spot by the St. Johns Bluff as the site of their settlement, Fort Caroline. The site was within the territory of the Saturiwa, the Mocama Timucua chiefdom who lived along the river and the barrier islands around its mouth. Laudonnière and the principal chief, also known as Saturiwa, forged initially friendly relations and exchanged gifts.

The following day, June 30th, 1564, the French rose at dawn for a ceremony of Thanksgiving before beginning work. As Laudonnière wrote in his account of Fort Caroline:

“The next morning at daybreak I ordered a trumpet to sound so that we could assemble and give thanks to God for our favorable and happy arrival. We sang songs of thanksgiving to God and prayed that it would please Him of His holy grace to continue His accustomed goodness toward us, His poor servants, and to give us aid in all our enterprises so that all might redound to His great glory and to the advancement of our king. The prayers being ended, everyone began to take courage.”

Laudonnière doesn’t say which hymns were sung, but it would have been a selection from the Huguenot Psalter, first published by John Calvin in 1539. Laudonnière also doesn’t mention a meal taking place after the ceremony, but if there was one, it likely comprised the ships’ meager rations given to the French as a gift from the Saturiwa. French ship rations comprised mostly dried salted beef, hardtack ship biscuits and cider. According to a member of the expedition, the artist Jaques le Moyne, the provisions gifted by the Saturiwa were much more varied, including “grains of maize roasted, or ground into flour, or whole ears of it; smoked lizards or other wild animals, such as they consider great delicacies; and various kinds of roots, some for food, and some for medicine.”

Thanksgiving at St. Augustine

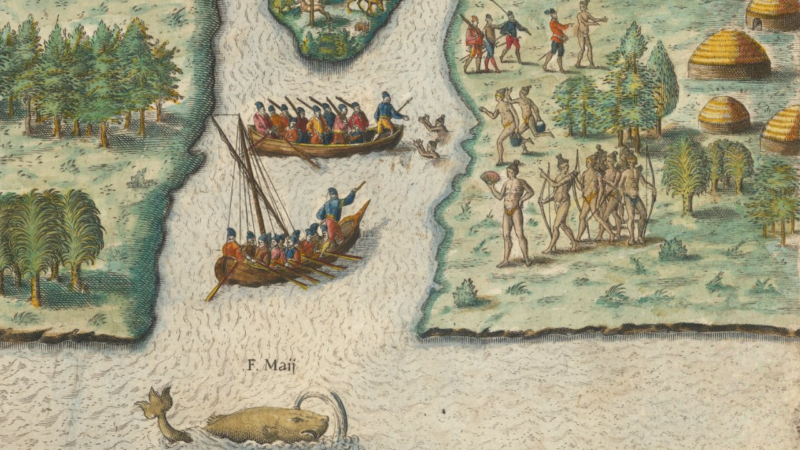

The French presence in Florida sparked a reprisal from the Spanish, who had claimed the land since 1513. A Spanish expedition led by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés had the goal of evicting the French and establishing a permanent settlement and defenses. Ultimately, this would lead to the capture of Fort Caroline and the execution of most of the French settlers.

On Aug. 28th, 1565, Menéndez’s expedition sighted land and anchored at what’s now known as Matanzas Inlet. After spending the next few days reconnoitering and skirmishing with the French, they returned to the inlet on Sept. 6th, landing near the Timucua town of Seloy at what’s now the Fountain of Youth Archaeological Park. The Spanish took over Seloy and fortified it as their base of operations. Menéndez named the settlement St. Augustine, as the day they first spotted land is the feast day of St. Augustine of Hippo.

On Sept. 8th, the feast of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Menéndez arranged a formal proceeding in honor of the fleet’s arrival. According to Father Francisco López de Mendoza Grajales, the expedition’s priest, “the general landed with many banners spread, to the sound of trumpets and salutes of artillery.” López, who was already ashore, took a cross and went to meet Menéndez, singing “Te Deum laudamus,” a hymn of Thanksgiving. Menéndez and his company knelt and embraced the cross, and López performed a solemn mass in honor of the Virgin Mary. López wrote that a number of the Seloy were in attendance for the ceremony.

After the mass, one of the first in the continental U.S., Menéndez continued with another ceremony taking formal possession of Florida. Another chronicler of early St. Augustine, Gonzalo Solís de Merás, wrote that after these proceedings, Menéndez hosted a meal for the Spanish colonists and the Seloy. He doesn’t mention what was served, but it would have prominently featured typical Spanish naval provisions such as hardtack ship biscuits, wine and cocido (a stew of salted pork, garbanzo beans and garlic), and possibly local food brought by the Seloy.

The Thanksgivings celebrated by the French and Spanish colonists of Fort Caroline and St. Augustine were one-time affairs, not repeated like the English celebrations in Virginia and Massachusetts. As such, they were largely unknown until the 20th century. Nonetheless, these accounts offer a glimpse of what a communal celebration was like in the First Coast for some of its earliest European guests.