This is Part 2 of a two-part Jacksonville Today series. Read Part 1.

For decades, Madelyn Dinkins-Smith’s family members have been buried in Gross Cemetery in rural Nassau County. Her grandfather, grandmother, aunt and uncle are laid to rest in the rural plot in a Rayonier-owned forest — a place where some of them worked in logging for the timber company.

The family burials at the cemetery span from at least the 1970s to the early 2000s. Dinkins-Smith says in earlier years, it was simple to visit her buried family members. She’d call or send a text to a designated Rayonier employee – the same woman for years – pick up the key, unlock the gate and go to their grave sites.

But in recent years, she says, it’s become much harder to schedule visits. And her concern is growing as Rayonier and Nassau County move forward with plans to expand Wildlight, a planned community off I-95 that covers at least two Gullah/Geechee cemeteries. (The coastal Gullah/Geechee Nation stretches from North Carolina to Jacksonville and traces its roots to primarily West African ethnic groups who maintained their language and culture during and after enslavement.)

“I just feel like the community, especially the Rayonier community, have forgotten about us and the verbal agreement that the families have made with them over the years,” Dinkins-Smith says.

Private property owners are required to maintain cemeteries and provide descendants access to family burial sites under Florida law, but these provisions can be hard to enforce, and the Florida Legislature shot down a bill aimed at closing loopholes in those requirements earlier this year.

In a statement to Jacksonville Today, Rayonier says descendants can contact the company and sign a waiver in order to visit their family cemeteries — a safety measure as hunting clubs regularly visit the area. “The process we’ve put into place allows us to provide notification to all parties, while adhering to our internal safety protocols and following the regulations of burial sites,” Rayonier writes.

But the legal gaps in ensuring descendant access are especially salient in Nassau County, where archeologists say dozens of Nassau County burial sites aren’t mapped correctly in the Florida Master Site File, which developers use to ensure they don’t disrupt cultural resources.

Legal gaps leave privately owned cemeteries vulnerable

In state law, “Chapter 872 is supposed to protect any human burial site in Florida, no matter who owns that land,” Florida Public Archeology Network archeologist Sarah Miller says. “That’s great, but it doesn’t really say who’s going to enforce this, especially when it gets into county-owned versus private-owned versus federal-owned.”

Dinkins-Smith says scheduling cemetery visits has been nearly impossible in recent years. Beyond calling for easier access, she wants recognition of her ancestors’ contributions to Rayonier in its vision for the future.

“I want Rayonier and the Raydient company [Rayonier’s development arm] to recognize and honor our family members for getting them to where they are, because they sacrificed. That’s backbreaking work,” Dinkins-Smith says.

Rayonier subsidiaries have marketed the nickname “FloCo” for the Florida Lowcountry – the geographic and cultural term for the coastal South. The branding for Wildlight homes centers on this idealized imagining of lowcountry living: walkable streets, open porches and connection with nature.

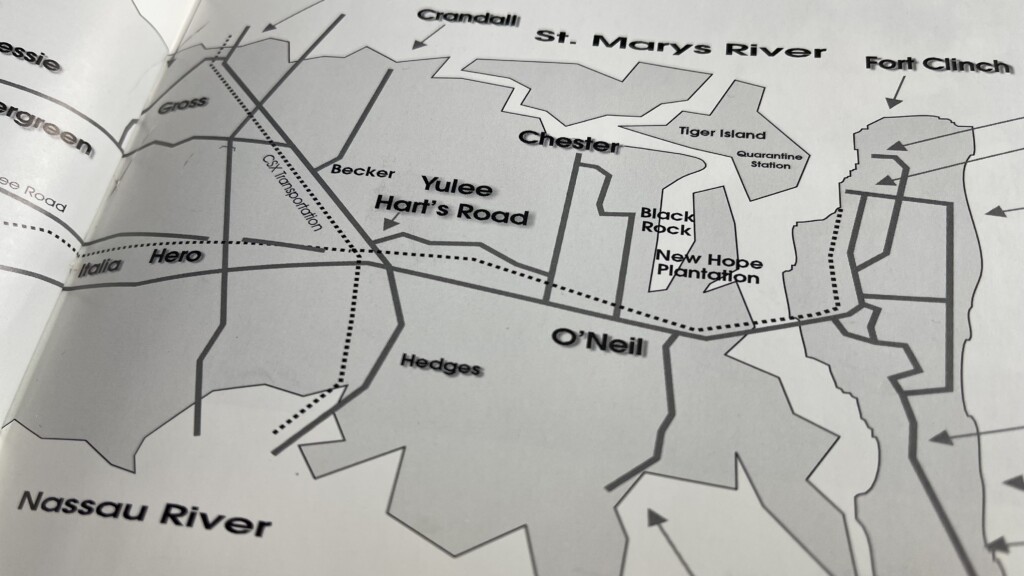

But Black descendants of the Nassau communities of Piney, Hero, Crandall and Gross say the communities their families forged are being repackaged and sold to a new audience, while erasing the past. Their push for preserving the cemeteries means also recognizing the communities Wildlight is replacing, descendants say.

“For the people that you sell these houses to – you push the family lifestyle and you take that away from other people – it’s not right,” Dinkins-Smith says.

In a written statement to Jacksonville Today, Rayonier says: “The legacy of the lands we own is an important story to Rayonier. We have owned this particular land for more than 80 years, and celebrating the history of the communities and the land’s heritage will be a story that is told as the development progresses.”

Recommended changes to Florida law from the state’s recently established Abandoned African-American Cemeteries Task Force could have given the county and Gullah/Geechee Nation stronger tools for ensuring the burial sites are protected, but the Florida Legislature didn’t pass them this year, despite bipartisan support in the House (including from local representatives).

Among the recommendations in the task force’s almost 200-page report is expanding who’s authorized to access cemeteries to include community representatives, instead of just traceable descendants. In Nassau County, this would have allowed Gullah/Geechee representatives to access the property and ensure maintenance laws are being followed, if direct descendants aren’t local.

The task force also recommended including cemeteries in conservation easements, through which property owners give up development rights. Another recommendation: local governments could establish protective covenants and use eminent domain (public seizure of property) to preserve privately owned cemeteries.

But in March, Florida lawmakers let the bill die that would have implemented some of the recommendations, including creating an office in the Department of State focused on protecting cemeteries.

“It’s very frustrating. One year to get the bill passed to have the task force. One year for the task force to meet, and then the failure of the Legislature to get the bill [implementing the recommendations] passed,” Miller says. “It just identifies the problem, but makes no solution for it.”

The bill nearly passed the House, but it died in its first Senate committee. Senate sponsor Janet Cruz, D- Tampa, has vowed to reintroduce the bill in the next legislative session.

Burials threatened before

Gullah/Geechee descendants say this battle for protections in Nassau County isn’t new. In 2019, the Rayonier subsidiary Wildlight LLC transferred a plot of land in the Piney neighborhood to a land trust, an arrangement that often allows property holders to avoid tax liability in exchange for giving up development rights.

But a planned retention pond on the land would have encroached on a burial site behind Harper Chapel Baptist Church in Piney that was, at the time, recorded only in oral histories and family knowledge.

Elder Gloria Thomas, with the Gullah/Geechee Nation Wisdom Circle Council of Elders, has family members who helped build the church and told her about the burial grounds — “My great-grandmama used to live back there, and she would bring the basket up with the biscuits and the ham and the sauces and water, tea, and she would feed the guys building the church.” Elder Thomas remembers a man being buried behind the church when she was a young girl.

She says, when a developer started walking through the church property, she got Gullah/Geechee representatives and the Florida Public Archeology Network involved. “This is our historical church. This is our history. It’s not for sale,” Thomas says. “Wildlight can go anywhere they want. Wildlight came into Piney, so we’re not gonna change and you’re not gonna take it from us.”

Eventually, Gullah/Geechee Nation representative Glenda Simmons-Jenkins and FPAN added the cemetery to the Florida Master Site File in June 2021. The stormwater drainage pond plan for Crossings at Wildlight was shrunken to account for burials, the state record shows.

But the protection was a close call, Simmons-Jenkins says, and may have come too late. She says the county still hasn’t established definite boundaries for the Harper Chapel cemetery and destruction may have already happened before the last-minute development change. That’s what she wants to avoid for the other burial sites, like Gross and Crandall cemeteries, in the planned Wildlight community.

“It’s not necessarily the outcome that I had hoped. It is an outcome that is a good one,” Simmons-Jenkins says of the Harper Chaper cemetery. “We had originally hoped that there would be something official that would say that that area is actually an easement, that it would exist in perpetuity to protect the burials.”

The path forward

Nassau County planner Thad Crowe says, as it stands, “If the county is going to recognize and protect historic archeological cultural resources, it requires the approval of the property owner.” He hopes Rayonier will give that approval through a detailed maintenance and preservation plan in a forthcoming updated Wildlight development agreement. If not, he says, the county’s options for protecting the gravesites are limited.

Another option under current Florida law: If the property owners don’t maintain burial sites, descendants are allowed to take over — but that would also require cooperation from Rayonier.

Nassau County this year hired Terracon, a historic preservation firm, to provide an independent report about Crandall Cemetery, which, like Gross Cemetery, is within the Wildlight development plan. Terracon’s Patricia Davenport-Jacobs says for descendants to take over maintenance permanently, it would likely “need to be an agreement that is crafted between the two parties, almost as a memorandum of understanding.”

Terracon’s final report on Crandall Cemetery isn’t completed yet, but Davenport-Jacobs says her recommendation is “a preservation plan put in place for the descendants so that they know how their loved ones, or the land that their loved ones are buried on, how that’s going to be maintained.”

In the absence of local or state government action, and no specific plan from Rayonier, Gullah/Geechee Nation representative Glenda Simmons-Jenkins says she will keep calling for public easements to preserve the sites.

Gullah/Geechee community members have also started fundraising for legal representation for families with relatives buried on the lands where they once lived and worked.

This is Part 2 of a two-part Jacksonville Today series. Read Part 1.

If you have family buried in Nassau County and have been unable to visit them or are unsure of how protected they will be in the future, please contact reporter Claire Heddles at claire@jaxtoday.org or at (904) 250–0926.