This is Part 1 of a two-part Jacksonville Today series. Read Part 2.

Deep in the woods of Nassau County, on Rayonier-owned logging land near the St. Marys River, is a fenced-in area with a few dozen stakes in the ground. Each one marks a likely grave site. A “No trespassing” sign hangs on the gate.

This historic Gullah/Geechee cemetery, known as Crandall Cemetery to descendants of those buried here, is part of an area zoned for resort development in Wildlight, the sprawling planned community off I-95. Rayonier developers have pitched Wildlight to potential homebuyers as a “green field” and a “town from scratch” — descriptions that don’t ring true for Black residents whose family members lived and worked on the land in the turpentine and logging industries.

“I refuse to be erased, because this place was built on the backs of our foreparents and our fathers,” says Elder Gloria Thomas, with the Gullah/Geechee Nation Wisdom Circle Council of Elders. Her dad drove pulp wood trucks for Rayonier. She is among the descendants fighting for access to and protection of burial grounds in Nassau County, adding new friction in an ongoing battle between the county and Rayonier over Wildlight.

Inaccurate boundaries and legal loopholes make Florida’s burial preservation laws hard to enforce on private land. And Raydient, Rayonier’s development arm, has yet to share a clear plan for protecting the sacred sites – despite the county’s request for one after Gullah/Geechee descendants sounded the alarm.

“The most important part of this process moving forward is that, as Rayonier develops and sells land, this property is maintained for the access of family members and for the general public,” Gullah/Geechee Nation representative Glenda Simmons-Jenkins says. (The coastal Gullah/Geechee Nation stretches from North Carolina to Jacksonville and traces its roots to primarily West African ethnic groups who maintained their language and culture during and after enslavement).

Rayonier purchased rural Nassau land in the late 1930s, and many workers and their families lived on the property to be close to the logging work. Simmons-Jenkins says, people “need to know that Gullah/Geechee people lived and worked in these woods. They need to understand that the history of Rayonier and our history, that the two are not separate.”

State burial records likely inaccurate

In Crandall Cemetery, there are just a few formal headstones remaining. One headstone reads “Oliver Hendson, 1897 – 1963,” part of why a county-funded surveyor dubbed the site Henderson Cemetery in the early 2000s. That name lives on in state records, though it’s not what descendants call it.

“Put up some kind of marker: ‘Crandall Cemetery,’” says Enoch Dinkens, who has family buried there. “The town was called Crandall.” His grandparents were buried in the cemetery in the 1960s, and his brother in the early 70s.

Another descendent, Denese (who asked to exclude her last name for privacy) says her father buried three children who died in infancy in Crandall Cemetery between the late 1940s and early 1950s. She describes him as a skilled fisherman, gardener and hunter, as well as a logger for Rayonier. “He was in pulp wood. It was a very, very hard job,” she says. As Wildlight’s expansion moves forward, she says she wants clear acknowledgement “that there were other people that were here and that they all played a pivotal role in the construction of this area. A lot of blood, sweat and tears were shed.”

Enoch Dinkens says 15 to 20 people were already buried on the Rayonier-owned land when his grandparents were. But the total number of people buried in Crandall Cemetery, during the decades families lived and worked here, is still unknown.

The cemetery’s true size is likely as misrepresented as its name is in the Florida Master Site File, which developers use as a reference to ensure they don’t violate Florida law by damaging known burial grounds and other protected cultural resources. Simmons-Jenkins, who has been working with the Florida Public Archeology Network (FPAN) to track death records, says burials in Crandall Cemetery likely date back to at least the 1910s.

Sarah Miller with the FPAN urgently warned Nassau County planners earlier this year about dozens of cemeteries like Crandall.

“Out of 70 cemeteries in Nassau County, only six we can say with certainty are mapped in the correct location,” she wrote in March. “While our office is working to correct the mapping discrepancies, we feel the situation for African American cultural resources in Nassau County is dire.”

She says the rural landscape, land purchases by private developers and systemic racism can all contribute to the inaccurate state files. “There’s definitely differential preservation that shows a long tenure of racist policies,” Miller tells Jacksonville Today. “That happens across Florida — Northeast Florida especially.”

Crandall Cemetery was first recorded in the file as Henderson Cemetery in 2004. The surveyors, Bland & Associates, made a rough visual estimate of its burials, but descendants’ voices weren’t included, according to state records.

“While the cemetery is somewhat maintained, trees have begun to encroach upon the graves,” the surveyors wrote in 2004. “The oldest legible gravestone within the cemetery dates to 1963, while the most recent dates to 1966. The only family names represented within the cemetery appear to be Henderson.”

During a recent visit to the cemetery by archaeologists — requested by county planners, at the urging of Gullah/Geechee descendants — Miller noted today’s fenced boundary is actually well outside the 2004 state-recorded footprint of the cemetery.

Gullah/Geechee Nation representative William Jefferson was a pallbearer for a friend’s funeral at Crandall Cemetery in high school, more than 40 years ago. He says there are likely dozens more people buried there than was immediately obvious in 2004.

“It looked like a slave cemetery, if I remember. That’s how that cemetery looked to me,” Jefferson says. While the known burials in Crandall Cemetery are post-Civil War, Jefferson says, “If they would have had headstones, they would have been made out of wood.” If not, burials were marked by what families had access to — sometimes, household objects.

Enoch Dinkens says his 17-year-old brother was buried in Crandall Cemetery in the early 1970s with a wood headstone that would likely be deteriorated by now. He says the last time he visited the cemetery was in the early ‘80s, when his father got a key from Rayonier and led the way through the woods to it.

Descendants believe there are likely burials outside of Rayonier’s fenced boundary for the cemetery, too. They’re calling for a formal analysis, and clear protection plan, before any development begins in the area.

Fighting for protection

At least three cemeteries have been identified within the planned Wildlight development: the Gullah/Geechee Gross and Crandall cemeteries and the majority-white Cemetery Yulee. In response to questions from Jacksonville Today about protection plans, Rayonier writes, “These specific cemeteries are still more than a decade away from having any development activity around them, but as development approaches, we will coordinate with community stakeholders and regulatory agencies to ensure access is maintained.”

But the descendants, and Nassau County planners, say the moment to make a preservation plan is now, before construction trucks can roll onto inaccurately marked grounds and potentially harm sacred sites.

In July, the county asked Raydient to provide “a package of protective and mitigative measures that will accomplish the intent of identifying, evaluating, and protecting archeological sites, and educating the public about local history through context-sensitive kiosks and education signs in public parks.”

Raydient has yet to produce those plans, and Nassau county has granted the company an extension on an updated Wildlight development application (which includes the burial sites) through December. County planner Thad Crowe says he’s hoping to see specific burial site protection plans by then.

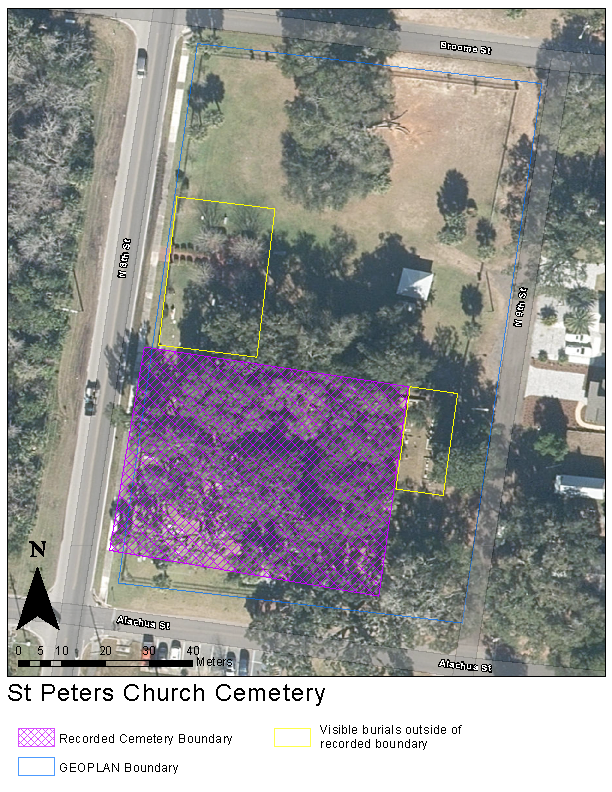

Aerial footage of St. Peters Church Cemetery in Fernandina Beach. The purple box represents the recorded cemetery boundary, and the yellow boxes show visible burials outside of the protected area. This cemetery is one example of inaccurate boundaries, but many of the Nassau Gullah/Geechee cemeteries are in heavily wooded areas, where grave sites are less visible on aerial footage. | Image courtesy of Florida Public Archaeology Network (Data source: Florida Master Site File)

Nassau County could also fund a historic survey to update the existing cemetery boundaries in the Florida Master Site File. But Crowe says the county has “literally been too understaffed” to apply for the grant funding to complete such a historic resources survey. Funding an updated county survey would require a Nassau Board of County Commissioners vote.

In the meantime, Gullah/Geechee Nation representative Glenda Simmons-Jenkins says she’ll keep fighting for the burials to be formally recognized, and honored. “The lives and the blood of our ancestors and our people are part of what makes Rayonier what it is today,” she says. “That’s a narrative that does not need to be overlooked, and they are resting here as evidence of that fact.”

This is Part 1 of a two-part Jacksonville Today series. Read Part 2.

If you have family buried in Nassau County and have been unable to visit them or are unsure of how protected they will be in the future, please contact reporter Claire Heddles at claire@jaxtoday.org or at (904) 250 – 0926.