The Age of Cognizance, which opened this month, is the Yellow House’s first in-person exhibit in nearly two years.

A group show of new works by Ricder Ricardo, Mimi Tran and Kirsten Williams, Age of Cognizance features each artist’s work in separate rooms. Tran’s lithographs and silkscreen prints on Vietnamese dresses occupy one bedroom, while Williams’ half-dozen or so paint-on-wood-block portraits hang in another. Ricardo’s vibrant figurative paintings have their own space in the Yellow House’s converted dining room.

Viewing each room in isolation makes the case that Ricardo, Tran and Williams emerged from a challenging year to create some of their best work to date. And then, hung along the hallways that connect the rooms of the Riverside home turned independent gallery space and hub for community action are several pieces that find each artist working outside of their comfort zones, either in collaboration with, or inspired by, one another.

The exhibition is at once an exploration of identity and a commentary on a laundry list of COVID-age transnational events––uprisings against authoritarian rule in Cuba, the treatment of undocumented immigrants at the U.S.-Mexico border, police brutality and the rise of hate crimes against Asian-Americans here in the states. Yet, Age of Cognizance is as much a show about gratitude, each artist finding affinity through collective consciousness during difficult times.

“This is the first time I’ve ever curated a group show in which the artists were all close friends,” says Yellow House founder and the show’s curator Hope McMath. “This deep love that they have for one another, that in and of itself, was a powerful story that they wanted to tell.”

Williams, Tran and Ricardo met as BFA students at the University of North Florida, tackling universal themes like art and politics in a relief printmaking class. A study abroad trip to Italy cemented their friendship.

“We got very close working late nights, bonding through our subject matter, overlapping themes of displacement and not feeling like you belong,” says Tran. “It’s obvious in our work how influential we are to each other; from themes, to mediums, and also the narratives.”

Though all three come from different backgrounds, Williams, Ricardo and Tran have found commonality in their multicultural heritage.

“The plan was to create a show about the integration of our different backgrounds and how we embrace our multiculturalism,” Ricardo says of the genesis of Age of Cognizance, which was originally planned for a pre-pandemic opening. “Nonetheless, after facing many challenges, including death, isolation, and political awakenings, all of which hit close to home, we had to create work about what it means to be human in the times of chaos.”

What it means to be seen is one of several themes each artist explores through portraiture and representations of the human form.

Many of Williams’ works, like the stunning “Pee Colored Girl,” are done on woodblock cutouts, which when combined with her framing of her subjects in classic or contrapposto-esque poses, creates a more-sculptural presentation that reframes feelings of inadequacy or trauma. “I want to tell relatable stories, but those stories that people have difficulty sharing,” Williams says in her artist statement for Age of Cognizance. “Most of the people that I ask to model for me don‘t believe they are worthy enough to become a work of art.”

Identity has always informed the work of Williams, who is of Swedish and African-American descent. In past exhibitions, like her recent Like-Minded at the Corner Gallery inside the Jessie Ball duPont Center, Williams has looked inward, using her family members as muses for exploring her biracial identity. Inspired in part by the Black Lives Matter protests in the Summer of 2020, Williams expanded her scope to tell the stories of strangers for Age of Cognizance.

“The protests during the pandemic changed my mindset. My two worlds were fighting against each other,” she says. “I wanted to shed light on biracial people or interracial couples who have gotten backlash from both races. It wasn’t about myself anymore.”

A first-generation Vietnamese American, Tran’s work has often mined the struggle to form her own identity through nostalgia, memory and loss. Troubled by the rise in hate crimes against Asian-Americans and galvanized by movements like Stop AAPI Hate, Tran was moved to confront the present moment through preservation of her own past.

For Age of Cognizance, Tran makes use of figure and fabric. Vietnamese dresses––silk screened with intricate city maps and scenes from rural life––hang next to lithographic prints and collages of photographs, postcards and truncated snips of photo negatives.

Viewed together, Tran’s installations are at once historic preservation and confrontation.

“I’m really embracing my culture and heritage as well as dispelling stereotypes perpetuated against Asians,” she says. “I really had to unpack my own identity as a Vietnamese American. I’m obviously so much more immersed in American culture than Vietnamese culture, that I didn’t want that aspect to be lost. I also had to really sit down and do research about these racist stereotypes in order to understand myself and how much it impacts me.”

For the Cuban-born Ricardo, the uprisings against authoritarian rule in his native country weighed heavily on him as he prepared work for Age of Cognizance. Ricardo immigrated to the U.S. as a teenager, and his vibrant representational paintings of families, like the evocative “Camping Trip”––which features a father and his two sons looking contemplatively into the distance of vast and harsh landscape––investigate displacement, exile and migration.

“My own personal narrative changed when I witnessed the death of my husband’s father during the first wave of the pandemic,” Ricardo says of the impact the last year and half has had on his work. “Having experienced this trauma from his perspective and witnessing selfless acts of kindness from his family members for one another, made me want to create work about family bonds, human strength and resilience. Looking for truth behind mundane, everyday moments that seemed simple and ‘normal’ to the naked eye, but were full of love and intention is what made me want to showcase humanity and identity in different nuances.”

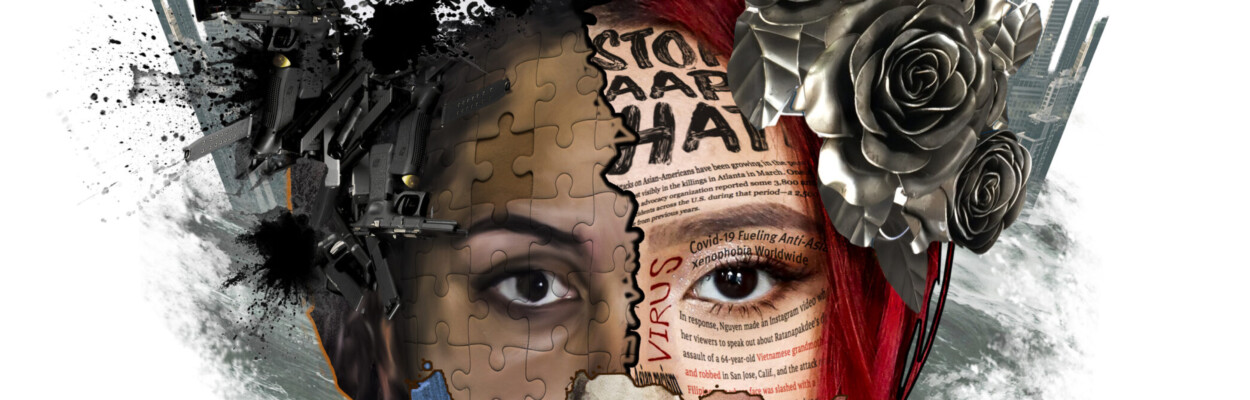

But while the work of all three artists is undoubtedly inward looking, Age of Cognizance is at least as much concerned with the sum being greater than its individual parts. Framing Ricardo’s large-scale “Camping Trip” is a grid of composite portraits featuring the likenesses of each artist bearing the weight of a headdress made up of protest signs and propaganda, roses and firearms––the burdens of the last 18 months carried not in isolation, but collectively.

“It meant a lot to me to be able to have friends who not only understood my work but also why I was so upset at what was happening in the world,” Tran says of bonding with Williams and Ricardo as the show was taking shape. “When these crises were happening, we were constantly having discussions in order to process how it was making us feel. We were able to relate to one another because we have experienced racism or oppression at one point in time.”

“It was important that all three voices were heard together and separately so that we could put together a coherent show,” says Williams. In addition to the composite piece, each artist painted portraits on wood-block cutouts in the style of Williams, with Ricardo using Tran and Williams as muses for his portraits.

“We all had different responsibilities and deadlines,” says Ricardo of the work involved in putting together the group show. “But ultimately we came together to make this great collaborative thing, in hopes that it would transcend.”

Age of Cognizance is on view at the Yellow House (577 King St.; Riverside) through December 22. The gallery is open to the public Wednesdays from 5 p.m. to 8 p.m. and Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m. Visit yellowhouseart.org for more information.