Two new projects in LaVilla and San Marco are creating something in short supply in Jacksonville: urban townhomes. Can they help Jacksonville’s “missing middle” housing problem?

The projects

Two townhome projects are currently moving forward in Jacksonville’s Urban Core: Johnson Commons in the Downtown neighborhood of LaVilla, and the Terraces of San Marco. Johnson Commons, a partnership between Corner Lot Development Group and JWB Real Estate Capital, will add 91 townhome units to the block surrounding Lift Ev’ry Voice and Sing Park, the birthsite of James Weldon Johnson and J. Rosamond Johnson. The Terraces of San Marco, to be built by Toll Brothers, will add 27 units a block over from East San Marco, a commercial development currently under construction that will bring a long-awaited Publix to the neighborhood.

As opposed to most suburban townhome developments, which are typically built as part of single-use residential complexes in the manner of apartments or condos, the LaVilla and San Marco projects will be built to mesh with existing walkable neighborhoods and will be surrounded by a variety of uses. As such, they’re providing something that’s in very short supply in newer developments in the Urban Core: a “missing middle” housing option between single-family homes and midrise apartments.

What is missing middle housing?

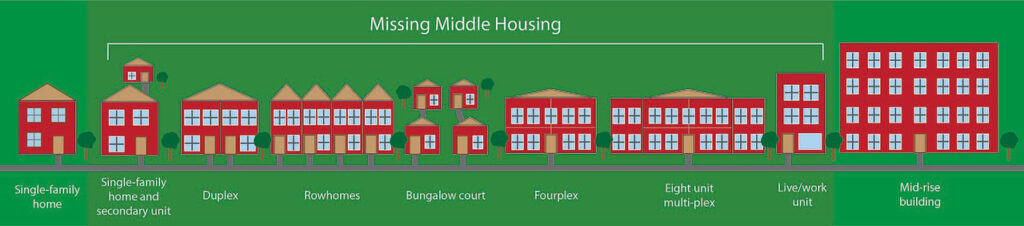

As laid out by the Congress for the New Urbanism, “missing middle housing” is “a range of multi-unit or clustered housing types compatible in scale with single-family homes that help meet the growing demand for walkable urban living.” The term was coined by architect Daniel Parolek in 2010, but the concept dates back centuries. In general, the missing middle comprises all the types of housing between single-family homes and larger apartment buildings. Examples include urban townhomes, row houses, duplexes, quadruplexes and single-family homes with secondary units (accessory dwelling units or ADUs), among many others. In general, these mid-density buildings provide needed options and alternatives for residents.

Historically, these types of housing were common in cities, and they helped create walkable neighborhoods with amenities near where people lived. Locally, they can be found in all of Jacksonville’s older neighborhoods, including Riverside, San Marco, Durkeeville, Eastside and Springfield. Springfield’s recently refurbished Dancy Terrace was one of the first “bungalow courts” in the country. Also historically common in Jacksonville, especially in Black neighborhoods, was the shotgun house. Developed from African building practices, tightly-packed shotgun houses were intended as affordable housing to combat overcrowding. Like other forms of missing middle housing, they served mid-density, walkable neighborhoods.

The missing middle is missing because after World War II, residential construction in most parts of North America has been dominated by low-density single-family homes and large-scale apartment buildings, with little in between. Jacksonville and many other cities have implemented zoning laws that encourage single-family developments, exclude other types of housing from them, and segregate residential property from commercial districts. This led to the creation of the modern, car-centered suburb and it virtually impossible to create new walkable areas.

Even in existing urban areas, construction of mid-density housing slowed to a trickle. There have been relatively few missing middle developments in Jacksonville in the last several decades; recent examples include the Parks at the Cathedral and small infill projects in neighborhoods such as Durkeeville and Murray Hill.

Benefits and hurdles of townhome developments

The main benefit of Jacksonville’s townhome projects is that they provide another option for residents that gels with a walkable community. As the Congress for the New Urbanism puts it, missing middle housing “provides a solution to the mismatch between the available U.S. housing stock and shifting demographics combined with the growing demand for walkability.” In many ways, LaVilla and San Marco are vastly different urban neighborhoods, but they have some things in common. They both benefit from new construction that increases their walkability, adds housing options of different levels of affordability, and supports neighborhood retail.

Also by The Jaxson on Jacksonville Today: The future of Bay Street depends on ‘clustering’

The LaVilla and San Marco projects are some of the few urban townhomes in Jacksonville, accompanying the proposed Springfield Lofts project by Tampa-based GNP Development Partners LLC in Springfield. Of late, new construction in and around both LaVilla and San Marco has been dominated by large apartment complexes.

According to Alex Sifakis, president of JWB Real Estate Capital and one of the developers behind LaVilla’s Johnson Commons, “You don’t see a lot of townhouses because the financial numbers don’t support them.” As zoning in most of Jacksonville – including in the Urban Core – actively discourages townhomes and other forms of missing middle housing, developers face hurdles in getting them off the ground. Urban townhome developments typically require large tracts of property, and developers can find it difficult to assemble enough small lots into a large enough property.

There are also zoning hurdles. As local zoning in most of Jacksonville discourages the product type, townhomes require a developer to first assemble properties and then pursue a Planned Unit Development (PUD) to change the site’s zoning. For many, it’s simply too much trouble to buy a bunch of small properties and then go the PUD route, a time consuming process that can be contentious depending on the neighborhood.

Ways forward

Sifakis sees potential for townhome-style projects popping up in or near old warehouse districts like the Rail Yard District and New Springfield, where it is cheaper to assemble block-sized lots than in Downtown or established residential neighborhoods like San Marco. Additionally, smaller products like duplexes and quadruplexes could be built more cheaply on smaller parcels of land than townhomes. In fact, the city of Jacksonville already owns many smaller lots that could fulfill this purpose, but developing them would require the city to sell them or give them away. And that’s contrary to the city’s typical practice of just hoarding them like the dragon from The Hobbit.

Another option would require a bit more work, but would be worthwhile: The city can update its zoning rules. A number of cities in the U.S. and Canada, including Minneapolis and Vancouver, have changed city zoning to enable more housing types. Portland, Oregon, where housing costs have risen dramatically in recent years, has even done away with single-family zoning as a distinct zoning category entirely.

One Jacksonville neighborhood is attempting to chart a different path. The Eastside has embraced a withintrification plan, a strategy to combat the negative aspects of gentrification, in which planning and investment are driven by current residents rather than outside developers and newcomers. In response to the community’s desire for more affordable housing, a new zoning overlay is in the works that allows for more missing middle housing. Developers are already lining up, so the Eastside could soon serve as a model for other Jacksonville neighborhoods hoping to plug the missing middle.