Harriet Beecher Stowe lived in an oasis of oranges, her windows overlooking groves of golden citrus and silky blossoms.

The Connecticut author and abolitionist — of Uncle Tom’s Cabin fame — tended to an acre and a half of citrus trees in her winter home of Mandarin. The humble plot produced 60,000 fruits per year, each one celebrated and prized by Beecher Stowe.

“The fragrance has a stimulating effect on our nerves, a sort of dreamy intoxication,” Beecher Stowe wrote in the 1873 travel guide Palmetto Leaves.

The oranges in New York markets, she said, “have not even a suggestion of what those golden balls are that weigh down the great glossy green branches of yonder tree.”

Florida citrus was born in St. Augustine, sprouting in the 1500s from a pocketful of seeds aboard a Spanish ship, a flowery display of colonial power amid many brutal ones. The industry took root in the northern part of the state, its heat and humidity reminiscent of the crop’s Southeast Asian origins.

Then came the frosts.

In the Great Freeze of February 1835, it was so cold people walked on the St. Johns River. Citrus groves dropped their fruit with defeated thuds. Growers moved south to Central Florida’s warmth. Another extreme freeze from December 1894 to February 1895 pushed out the stragglers.

The southward crawl continued throughout the 20th century. Polk, Hendry and DeSoto counties became industry leaders until a blotchy bug, about the size of a grain of rice, spread a multibillion-dollar disease.

Orange production in Central and South Florida fell 92% between 2003 and 2023. In the past five years, the region has lost acreage the size of Atlanta.

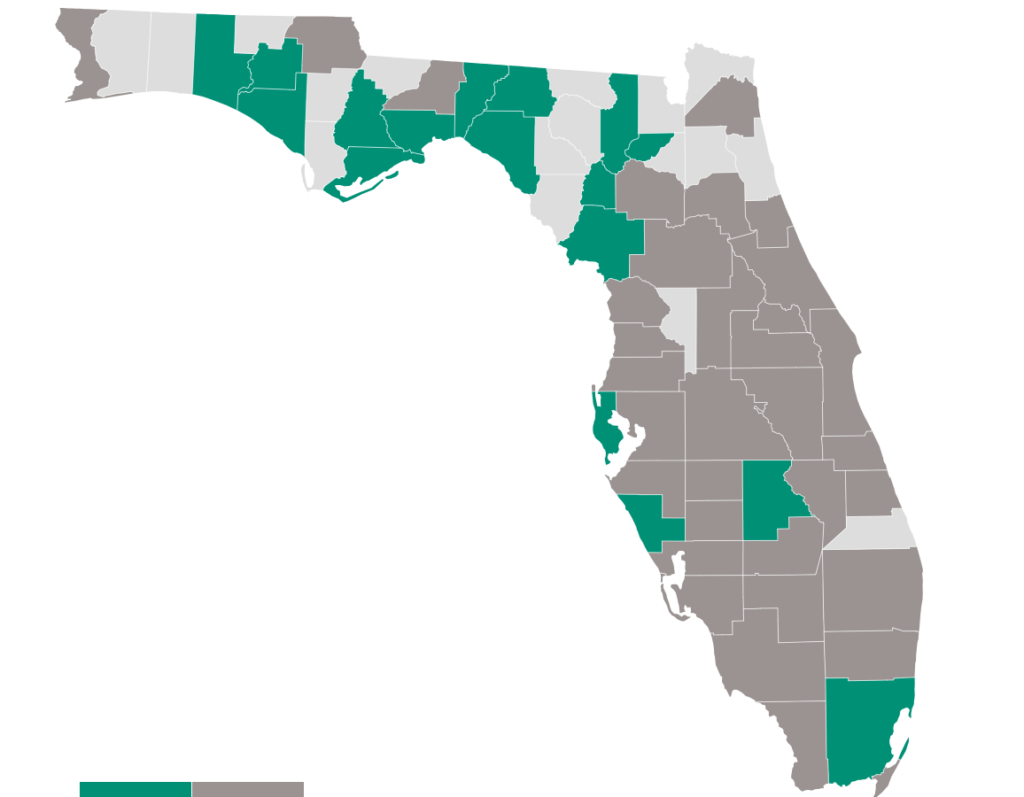

Yet in the same span, citrus acreage in North Florida — from Levy to Escambia County — has doubled.

As Central and South Florida growers battle the bug, their northern neighbors champion a sort of homecoming, more than a century after Beecher Stowe.

This new wave of producers has irrigation technology their predecessors didn’t and a winter climate as warm as an 1890s spring.

Armed with cold-hardy varieties and a new brand identity, they sink their shovels into sandy soil, confronting challenges old and new.

Citrus hardiness in Tallahassee

On an east-facing slope outside of Tallahassee, young citrus trees hide beneath a canopy of mature pines like shy children nervous to leave a parent’s side.

The strategy protects Satsuma mandarins, Hamlin oranges and grapefruit from the region’s biggest threat: the cold.

Louise Divine and Herman Holley of Turkey Hill Farm bought the land in 1999. The couple, both in their 70s, grows a bit of everything: fig trees, grapes, ginger, turmeric, half a dozen kinds of turnips and sugarcane, selling at farmers markets and local restaurants.

They introduced citrus in the early 2000s, starting with only four trees. Today, they have 35. At such a limited scale, Holley doesn’t call himself a citrus grower. “We’re market gardeners, and citrus is just a part of our diversity,” he said. “It’s quite a viable thing on a small, diversified farm.”

For now, small groves like Turkey Hill’s are the regional industry’s norm. Six North Florida counties have only single-digit citrus acreage.

Most trees in Tallahassee are only 6 to 8 years old. They’re green and vulnerable, especially to freezes.

North Florida varieties of mandarins, sweet oranges and grapefruit are naturally cold-hardy and grafted onto the woody rootstock Poncirus trifoliata for extra frost protection. Still, a tropical fruit is no match for ice-cold temperatures.

Christmas 2022 proved it.

From Georgia to Ocala, temperatures plunged below 30 degrees for six days straight, sending growers scrambling to irrigate and warm groves between stuffing stockings and opening gifts.

“Nobody expected that,” Holley said. “That was a killer.”

Farmers lost all fruit they hadn’t harvested. Canopies shrank. Water in tree trunks expanded, splitting bark with infamous “freeze cracks”: an entrypoint for pests and disease. It was as if the Great Freeze had returned. But growers had better tech than their 1890 counterparts — icy tunics to protect against wind chill and micro irrigation to harness the heat released as water freezes.

In the season after the freeze, some farmers took the barren trees in their groves as evidence that citrus wasn’t sustainable so far north.

Others saw the freeze as a rarity. Climate change is making winters warmer nationwide. According to Climate Central, the average winter temperature in Tallahassee rose 3.8 degrees between 1970 and 2022. Over the same period, cold snaps shortened by five days.

Even the Christmas freeze was warmer than its predecessors. During the 2022 freeze, the lowest temperature recorded in Tallahassee was 19 degrees. During the Great Freeze it was 11 degrees.

Turkey Hill lost much of its crop in 2022, but the next season was warm and fruitful. A year later, Holley walked through his shady grove to a surviving tree. He touched the dimpled orange rind, saying, “It came back.”

Marketability in Monticello

The very temperatures that threaten Panhandle citrus also sweeten it.

The North’s early, long cold spells cause trees to pump sugar into their fruits. It’s a biological tactic for self-preservation and the selling point of Sweet Valley Citrus, a burgeoning brand

Growers Kim Jones of Florida Georgia Citrus in Monticello and Mack Glass of Cherokee Satsumas in Marianna created the nonprofit in 2017. It brings together 40 members from North Florida and southern Georgia and Alabama.

“We formed this association to get people interested in growing citrus trees and planting groves,” explained Buster Corley, the association’s president and owner of Southern Tree Source in Monticello. “Once there was a niche industry developed here, it kind of morphed into more of a marketing group.”

As the tristate region’s groves expanded to 9,000 acres, the group received a grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture to launch the Sweet Valley Citrus brand.

“We’re still a long way from being well established,” Corley said, “but there’s a lot of interest in it, and we can really grow high quality stuff.”

Although the region’s production is on the rise, some experts are concerned about marketability. While fresh fruit fetches a higher price than oranges entering the juice stream, it’s a much smaller market. Florida is primarily a juice orange state.

Sweet Valley Citrus growers needed a variety that was cold-hardy, pest-resistant and reliable — and beggars can’t be juicers.

Nearly all citrus grown in the region is sold as fresh fruit.

Matt Joyner, CEO of grower advocacy group Florida Citrus Mutual, said while he’s excited to see the return of historical North Florida acreage, “everybody acknowledges you’re going to get to a point where you’ll saturate the demand for the fresh market pretty quickly.”

Enter: satsuma juice. Or, as Jones of Florida Georgia Citrus calls it on his storefront: “liquid fruit.” While the product won’t be on supermarket shelves anytime soon, it is an encouraging start to expand Sweet Valley Citrus beyond the bushel and into the bottle.

Pest control in Ochlocknee

Lindy Savelle and her husband, Perry, planted their first citrus grove in 2016. They formed Georgia Grown Citrus two years later, selling cold-hardy trees to homeowners and commercial growers. The nursery is a lush oasis of trees amid a sea of row crops in Ochlocknee, Georgia, 24 miles from the Florida state line.

In tandem with North Florida, South Georgia has experienced a surge in citrus production in the past decade, reaching nearly 4,000 acres in 2024.

“It’s just unbelievable,” Savelle said. “I mean, every day I’m learning of a new grower somewhere.”

In April 2023, Georgia Gov. Brian P. Kemp signed HB 545, creating the Georgia Citrus Commission to support and regulate the state’s growing citrus industry.

Its Floridian counterpart was founded in 1935 but includes only 36 counties in its regulatory reach, leaving North Florida growers in limbo.

A spokesperson for the Florida Citrus Commission wrote in an email to WUFT that there are not currently any plans or talks of adding counties to the regulated area.

And, according to growers, there’s no need, unless the Asian Citrus Psyllid infiltrates Sweet Valley.

The soft-bodied, plant-feeding insect arrived in Central Florida in 2005, quickly spreading its destructive bacterial cargo, Liberibacter, throughout the state. Look at any grove in Central Florida and you’ll see its effects: Small, hard fruits look like dip-dyed easter eggs, their orange ombres interrupted by walls of green.

While the psyllid has made its way to Sweet Valley Citrus, greening hasn’t ambushed the region’s groves as much as it has in Central Florida. Georgia logged its first case this year.

As Savelle drafts Georgia’s statewide action plan to prevent an outbreak, she looks more to California than to Florida for guidance.

“People tell us all the time that what California is doing is working. Believe it or not, we are more similar to California than we are to Florida. I know that sounds crazy, but that’s the truth,” Savelle said.

Researchers agree. Lauren Diepenbrock is an insect ecologist at the University of Florida’s Citrus Research and Education Center in Lake Alfred, just east of Lakeland. She studies the Asian Citrus Psyllid and other insects in the “piercing, sucking, squishy-bodied organisms group.”

A Florida native, Diepenbrock watched the industry collapse firsthand. “This part of Florida doesn’t look like anything like it did when I was younger,” she said. “You used to drive through Winter Haven and all you could smell was citrus.”

While she harbors a certain resentment against the psyllid (“there’s just something so satisfying about smooshing those little jerks sometimes,” she said), Diepenbrock knows their habits and behaviors like a lifelong friend.

They’re picky with humidity, she explained, needing it to keep their soft bodies hydrated but not so much as to mat down their wings. “They don’t love the cold as much,” she said. “They have a harder time with that.”

So, California’s lower humidity and cooler winters have slowed the psyllid’s spread compared to Central Florida. And Sweet Valley’s similar climate could do the same.

“It will be really, really interesting to see how they roll with this,” she said, noting, too, that small, distributed groves like the ones currently popping up in North Florida could help slow the spread. When a region isn’t “citrus on top of citrus on top of citrus,” she explained, “it takes a longer time for a lot of pests to find those habitats.”

Back in Monticello, Corley of Southern Tree Source hopes that logic will hold. “We have pockets of that and hot spots, but it’s not endemic here,” he said, “so we feel like we’ve got a little bit better control of it.”

Lessons from Mandarin

Today, citrus trees don’t drop pearly flowers onto the banks of the St. Johns River. Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Mandarin groves, with her prized golden fruit, have long been paved over.

The North Florida citrus industry emerging today is not the one that soured in the 19th century.

It is smaller, more technical and perhaps even more determined, carrying lessons, as Beecher Stowe described, from the citrus trees themselves: “full of sap and greenness; full of lessons of perseverance to us who get frosted down and cut off, time and time again, in our lives.”