In 1988, Jacksonville University professor George Hallam wrote that a tree-covered site between the school’s maintenance facility and University Boulevard North was “a small cemetery … a forgotten part of a colorful history.”

It was there that Jim Golden, JU’s housekeeping supervisor, rescued the toppled but intact headstone of Cpl. William Johnson, a Civil War veteran of the U.S. Colored Infantry who lived in Arlington.

Johnson was buried in 1892 with a military marble headstone next to a church that is now long gone. But sometime after Golden saved Johnson’s headstone, it was stolen, and his story — and that of the cemetery — drifted into memory.

Until now.

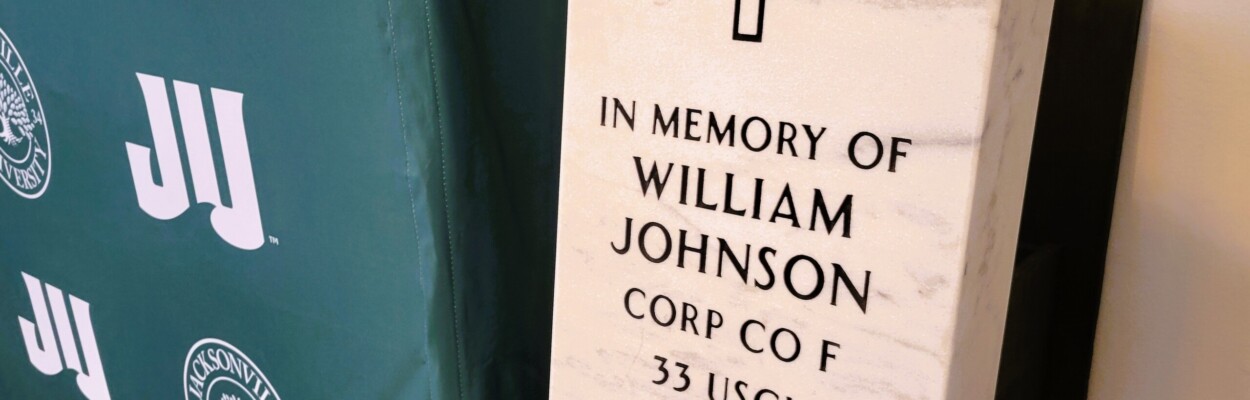

Now JU, the Local Initiatives Support Coalition Jacksonville and others and trying to restore the historic African American graveyard The first step was unveiled Tuesday — a proper new military headstone for Johnson.

“I envisioned it would just be, maybe we can get a headstone, and maybe we can put it up and a couple of us will be there, but it’s become bigger, and so many people rallying to it,” said professor Emeritus Craig Buettinger, who helped get the new gravestone as plans proceed to renovate the entire cemetery.

“We are working on figuring out everyone who is there — there will be a plaque with everyone’s name on it,” Buettinger said.

Restoring the cemetery with Johnson’s new headstone is important to this community, honoring a life that Kristopher Smith, LISC Jacksonville’s community development program officer, said particularly moved him.

“When that original marker was removed, it left a void in this community,” said Smith, an Arlington native as well. “We are here today to fill up that void. Our board, as community stakeholders, are about bringing together community, human, social, financial and spiritual capital. As far as I am concerned, the story of Cpl. William Johnson is a Netflix story, because it represents how coming together can bring about representing the best of us.”

Historical records uncovered by JU and others show that in 1863, Johnson joined the Union Army to fight the Civil War, enlisting in the 1st South Carolina regiment.

Johnson, then 21, rose in rank to corporal in the 33rd USCI, or United States Colored Infantry, according to a 2019 story on the campus website.

Records indicate that Johnson survived the war, ultimately moving to the Arlington area and marrying someone known only as “Miss Fannie.” He apparently lived near the cemetery, overseen by an African Methodist Episcopal Church in the 1870s, then by the Chaseville Road Baptist Church, since that is what the boulevard was known as then.

Johnson died in 1892, and a marble military headstone was erected two years later in the Arlington graveyard after the U.S. Army quartermaster approved requests from Miss Fannie, the local AME church and Grand Army of the Republic Black veterans group, Buettinger said.

The church burned in 1920, but the cemetery remained. In 1989, Golden recovered Johnson’s intact headstone and the remains of another before they could be stolen or vandalized, JU’s student newspaper, the Navigator, reported in 1989.

Golden organized a recognition service for Johnson, then he and other veterans cleaned up the site on Memorial Day 1989. The graveyard was soon fenced in for safety, and a sign was installed in 2006 with the names of a few buried there.

Late in 1989, Johnson’s headstone went missing. Buettinger, who had been involved since its discovery, notified LISC of the unmarked gravesite in 2022, after that group had launched “Operation Final Hours,” an effort that helps local families place headstones on unmarked burial sites of their military veteran family members. A request was made to the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs for a new one.

“When they applied for the … headstone — you are not going to believe this — the VA said ‘No, not us, we are not doing it,'” said U.S. Rep. Aaron Bean, a JU senior when the headstones were found. “So our team went to work and laid out the evidence of service to say this gentleman did serve his country and is entitled to the benefits thereof. And that is a glorious, beautiful, brand new headstone.”

Now the former graveyard site will be restored with a memorial monument and gazebo. Along with the unveiled headstone came a preliminary design to revitalize the graveyard to commemorate Black residents as well as military veterans laid to rest there.

“The basic thing is to make it a teaching moment about specific history, to get some kind of marker,” Buettinger said. “I worked here for a long time, and I knew there was a headstone that was missing, and I know we had (composer) Frederick Delius’ house. But I did not see JU and the area as having an interesting history until I got involved in looking more deeply into Johnson’s past.”

As members of the school’s Navy ROTC program sat in at Tuesday’s unveiling, JU President Tim Cost said the day after Memorial Day was an even more important time to recognize and celebrate history.

“Honoring on this campus everything from the Native American burial grounds to Civil War veterans and veterans of color is an incredibly important day,” Cost said. “We have said that we not only want to be in Arlington, but of Arlington. This is a day where we can celebrate the greatness of the history of Arlington.”

The final design for the new cemetery memorial will be done in time for the planned groundbreaking near Veteran’s Day, although the final cost and who will pay for it have not been worked out yet, Smith said.