Duval County’s infant mortality rate is higher than average for the state of Florida, especially among Black babies.

The challenges of closing the racial gap and reducing the overall rate of babies who die before their first birthday are the topics of a summit Tuesday in Downtown Jacksonville — the same day that the Jacksonville City Council is expected to approve a budget that eliminates part of the mayor’s proposed funding for a program to reduce infant mortality.

The Northeast Florida Healthy Start Coalition’s Community Health Workers program was funded by American Rescue Plan dollars. Mayor Donna Deegan sought to extend the health workers’ efforts by allocating $310,000 in the 2026 budget.

Those dollars would have funded two initiatives: $200,000 for Community Health Workers and $110,000 for congenital syphilis screenings. The Jacksonville City Council removed funding for the syphilis prevention initiative, leaving the funding for the Community Health Workers program in the final budget the council is expected to pass on Tuesday.

The infant mortality problem

In 2023, 7.9 out of every 1,000 children born in Duval County died before their first birthday. That’s compared to the 6 out of 1,000 Florida babies. The local figure had declined over the last five years, from 9.5 children out of every 1,000 live births in 2018, but it’s remained stubbornly higher than the statewide rate for the past decade.

Agape Family Health CEO Mia Jones says there could be a ripple effect if Duval County does not invest in reducing infant mortality.

Her nonprofit provides preventative services to those who are pregnant or hope to become pregnant. The Federally Qualified Health Center provides care to patients who earn under less than twice the federal poverty level. (For a family of four, that would be income of $64,300.)

Jones served on the Jacksonville City Council and in the Florida House of Representatives before she became Agape CEO in 2017.

“If we are not able ensure that moms are healthy enough to produce healthy babies, who ultimately grow up to be productive citizens, we put ourselves as a community in a space where one day we won’t be here. There won’t be enough of us to sustain the community that we desire to have,” Jones says.

Dr. Christopher Watson, a family physician who provides services at Agape, estimates he delivers about a dozen babies annually.

Watson finds the pregnant people who visit his practice often do not realize they are sick or the severity of their health issues. He says patients in underserved communities often lack awareness about the low-cost resources available to help reduce their risks.

Preeclampsia is a common and potentially dangerous complication Watson sees. That’s when a pregnant person has high blood pressure and often a high level of protein in their urine, and it often leads to early deliveries.

Preterm is defined as born before the 37th week of pregnancy. According to the March of Dimes, Jacksonville’s preterm birth rate of 12 children for every 1,000 live births in 2023 is higher than Florida’s (10.7 per 1,000 births) and the nation’s (10.4 preterm births per 1,000 births). Preterm birth and sudden infant death syndrome are two of the leading causes of infant deaths.

Federal policy effects

Other challenges Duval County faces in its quest to reduce infant mortality are the effects of federal immigration enforcement and impending federal policy changes about Medicaid eligibility, the clinicians say.

“With Agape ,we have a large Hispanic patient population,” Watson says. “With the current climate, there is a distrust or fear. ‘If I seek care. If I am lucky enough to make it to the hospital to deliver, I don’t know if I want to take the chance to go out with my child for follow-up appointments.’ (Some of my patients have) the fear of being arrested or deported.”

“At Agape, we have seen a drop off of our Hispanic patients coming to seek care,” he says.

Watson estimates fewer than 10% of his patients have commercial insurance. Nearly a third are on Medicaid, the federal health insurance program for low-income people.

When President Donald Trump signed the One Big Beautiful Bill into law on July 4, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimated 7.8 million people would lose access to Medicaid over the next decade. Watson says the legislation, which was supported by Northeast Florida’s full congressional delegation, will have an adverse local impact.

“With the lower reimbursements with people who have Medicaid, a lot of places will stop taking Medicaid, which will create a care desert for women.” Watson says. “With the laws and policies, I think we will see an increase in infant mortality (in Jacksonville).”

In the 2025 legislative session, state Sen. Tracie Davis, D-Jacksonville, introduced a bill that gave pregnant women presumptive Medicaid eligibility while a final decision on their eligibility was determined. The bill, meant “to increase access to necessary prenatal care for pregnant women in underserved areas,” died in committee.

Maternal care complications

Access to prenatal care has been spotlighted as critical to reducing infant mortality.

The Northeast Florida Healthy Start Coalition provides services that range from in-home nurse visits for first-time, low-income parents; a mobile pantry with diapers and other needs for parents with young children; targeted outreach to people in ZIP codes where infant mortality is a problem and more.

In an August 2023 application for a federal Maternal and Child Health Block Grant, the Florida Department of Health highlighted the efforts of the local Healthy Start Coalition’s Community Health Workers program because it provided resources and education to expectant and postpartum mothers.

The coalition’s work will continue with its Sept. 23 summit.

Meredith Smith will be its keynote speaker. Smith is executive director at Cradle Cincinnati, a nonprofit that has reduced infant mortality in Ohio’s third-largest county.

“What we are doing is centering Black women’s… voice and asking them what they need,” Smith told the PBS NewsHour earlier this year. “The uniqueness of this model is that, instead of it being how we see fit for you to receive care, we think about how you want to receive care. And that changes the way we understand caring for people in the U.S., period.”

Black children in Duval County are far more likely to die within their first year of life than white or Hispanic children.

In 2023, 13 out of every 1,000 Black babies died within their first year of birth. At the same time seven out of every thousand Hispanic babies and five out of every thousand white babies didn’t make it to theirs.

Duval’s Black infant mortality rate is higher than the 8/1,000 rate of Ukraine, a country fighting for its sovereignty, according to World Bank data.

A brighter beginning for parents

Cradle Cincinnati found it was able to reduce infant mortality through providing postpartum support groups like these and working to ensure the basic needs of mothers – including stable housing, reliable transportation and affordable childcare — are met.

Willie Roberts says it’s been a calling for most of her 52-year nursing career to provide community outreach and connect vulnerable people with resources.

“What we’re seeing in Duval, in this urban setting, we see a lot of poverty,” Roberts says. “We have a lot of moms that access prenatal care late in the stages of their pregnancy. I think it’s because they don’t know how to navigate the system. Lack of knowledge and resources. That’s something we do, share resources with the moms.”

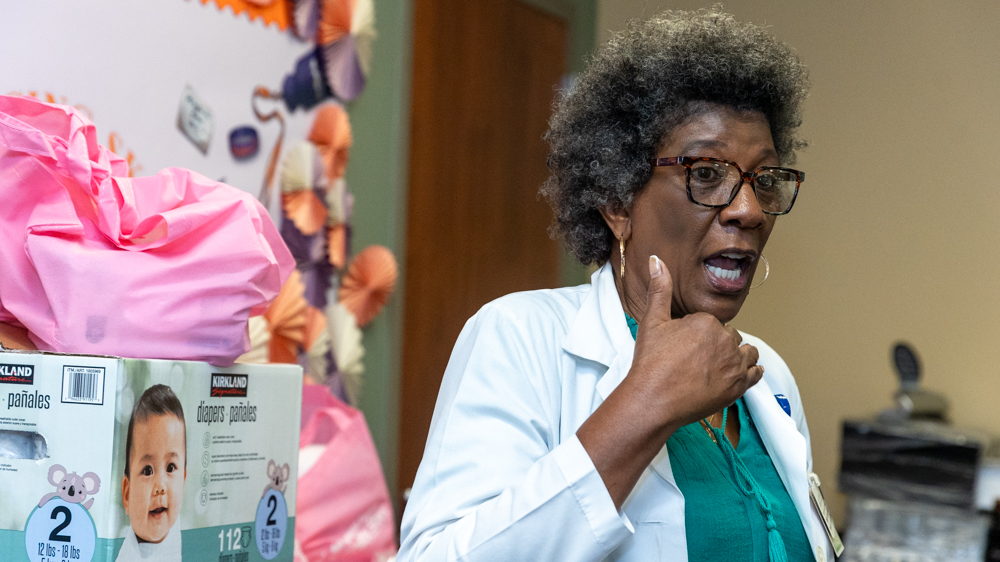

The “we” is Ascension St. Vincent’s Brighter Beginnings program. Brighter Beginnings partners with Feeding Northeast Florida to provide attendees nonperishable food. The program also provides diapers, formula and wipes.

And hospital staff hold workshops on the second Saturday of every month at the Center for the Prevention of Health Disparities at Edward Waters University. Since 2014, more than 1,000 women have participated in the program.

Naomi Grant and Kayla Way are first-time mothers who attended this month.

Grant’s son, Nolan, is 8 months old. Way’s daughter, Ky’Liah, will turn 7 months next week. The two mothers met during a community baby shower in the springtime and remained in touch.

Grant says she learned about postpartum depression during a Brighter Beginnings session.

“Usually, people don’t acknowledge that they have it,” Grant says. “The class helped me and it helped me get better so I could be a better mom for him.”

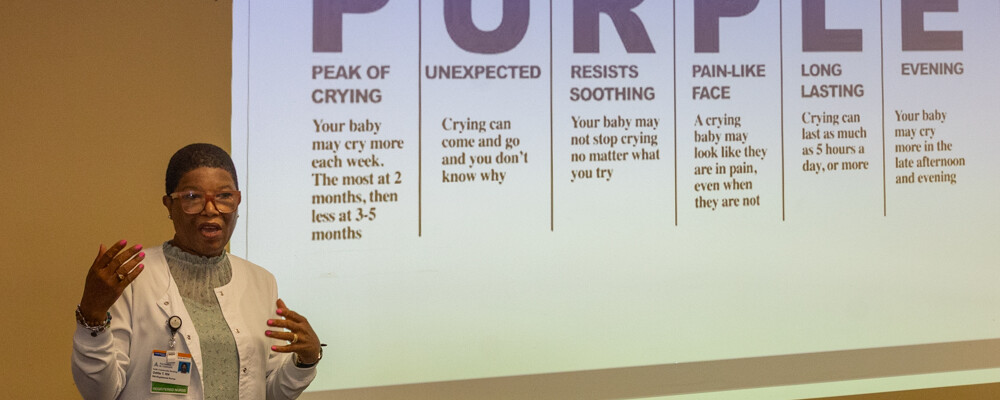

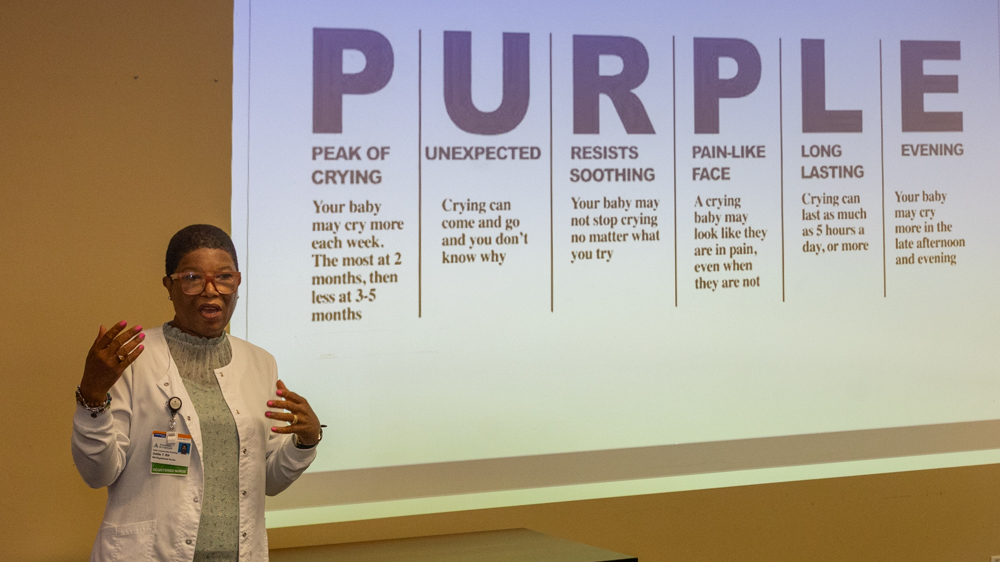

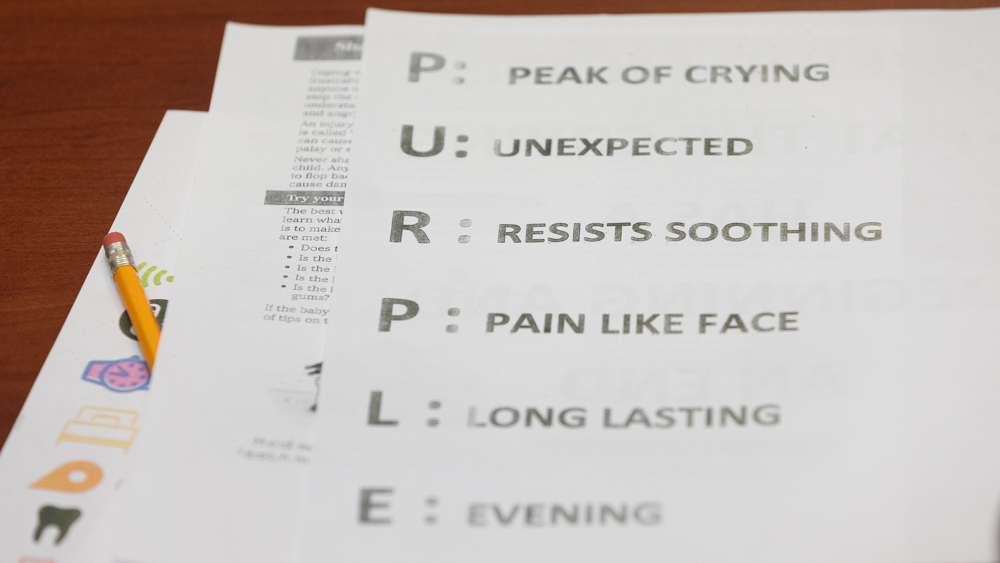

This month’s lesson taught parents how to identify a PURPLE cry. Roberts and fellow nurses Elaine Barney and Odille Thomas identified the symptoms that can signal shaken-baby syndrome or abusive head trauma.

“The whole purpose of this class…Duval County has the highest infant mortality rate in the state,” Roberts told the 15 mothers and caregivers on Sept. 13. “Infants are dying before they are 1! Thank God, your baby survived to age 1. What’s been happening is the babies are dying.”

While Brighter Beginnings offers instruction only in English, it’s seeking volunteers who can translate the lessons into Spanish.

One way the Brighter Beginnings program seeks to reduce infant deaths is to provide a portable playard like a Pack ‘n Play to parents who attend five consecutive classes.

Roberts says sleeping with a child in your bed is a leading cause of infant mortality.

“We advocate in each class, no matter what the topics are, in each class we talk about the importance of breastfeeding and safe sleep practices,” Roberts says. “We want to continuously drill into the moms that co-sleeping (is not good.)”

The mantra they teach the mothers is to remember their ABC’s: Baby should sleep “Alone, on his Back, in a Crib.”

Corrected on Sept. 22, 2025: This story originally said the City Council also cut the $200,000 for the Community Health Workers program from the budget, but only the syphilis screening program was cut. We regret the error.