Each year, the Getty Foundation and the African American Cultural Heritage Action Fund partner to offer a grant program dedicated to preserving modern architecture created by Black architects and designers.

Throughout the 20th century, these visionaries helped shape the modern architecture movement in the U.S. by innovating, experimenting, and redefining how people experience the built environment. Yet, despite their profound influence, their contributions have too often been overlooked and undervalued.

In Jacksonville’s own modern architecture story, John Burnie Caine is a living legend. This week, I had the privilege of meeting Mr. Caine as he prepared to celebrate his 95th birthday.

‘The Hill’ to Hampton

Born on October 21, 1930, in Jacksonville Beach, J. Burnie Caine grew up in a time and place that offered few opportunities for a young Black man with architectural ambitions. Yet, through persistence and passion, he built a career that left a visible mark on Jacksonville’s landscape and the city’s Black middle class.

Caine was the sixth child of Walter and Mable “MaDear” Caine, raised at 616 First Ave. S. in a neighborhood affectionately known as The Hill, so named because it sat on the beach’s highest elevation. The family’s life was deeply rooted in this community, where they ran a local gathering place called the Harlem Grill.

Because Jacksonville Beach had no high school for Black children, Caine commuted daily to Old Stanton High School in LaVilla. The trip was grueling: a nine-block walk to the bus stop, then a 45-minute ride each way at 25 cents per fare, followed by another walk from Bay and Clay streets to Broad and Ashley streets. Yet those long rides only strengthened his resolve. Summers brought opportunities to work alongside his father, building homes in a subdivision along Penman Road. There, he discovered his calling — architecture.

Segregation barred him from enrolling in Florida’s architecture programs at Florida State, the University of Florida, and the University of Miami. Undeterred, he enrolled in 1949 at Hampton Institute (now Hampton University), one of the few historically Black colleges offering architectural studies.

His summers were filled with hands-on experience. Thanks to an older brother who worked as a bricklayer for Hiron H. Peck Construction Co., Caine spent his breaks working on major projects such as the Gateway Shopping Center, local service stations, and even the Naval Air Station on Roosevelt Boulevard. Later, he joined two brothers on construction crews in Miami, helping to build landmarks like the Fontainebleau Hotel on Miami Beach.

Building a career against the odds

After serving honorably in the U.S. Army during the Korean War, Caine returned to Jacksonville, ready to start his professional career. But racial discrimination kept doors closed. Unable to find work as an architect, he took a job as a draftsman with J.E. Hutchins General Contractors. One of the few local African-American contractors who also designed their buildings, James Edward Hutchins designed and built several African American churches and residences throughout town.

However, for Caine, supporting his growing family meant juggling multiple jobs: sandblasting at the shipyards, working as a lab technician at Humphrey Gold Co., and teaching school, a career that would span four decades. Along the way, he found an ally in local white architect Britton Kirton, who helped him gain footing in the city’s building community.

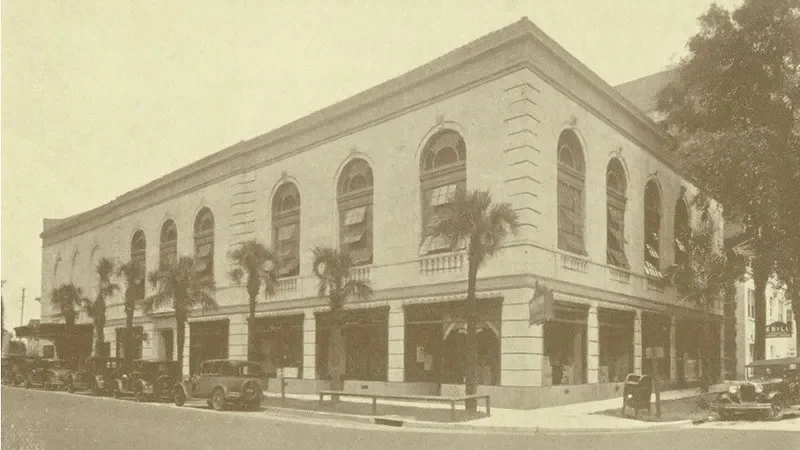

A lasting imprint on Jacksonville

Over the years, J. Burnie Caine became the go-to designer and builder for Jacksonville’s Black professional class. His architectural imprint can still be found across neighborhoods like LaVilla, Eastside, Durkeeville and Grand Park. But nowhere is his influence more concentrated than in Northwest Jacksonville, where rows of Caine-designed homes stand as enduring symbols of Black wealth and resilience during segregation.

Representative of many local Black professionals in the architectural field who were not fully recognized, Caine designed numerous homes during the mid-century modern period. His work often sought to blur the boundaries between indoor and outdoor living, featuring expansive windows, glass doors and patios that embraced their natural surroundings.

Each of these structures tells a story, not only of one man’s artistry, but of a community’s determination to thrive despite systemic barriers. Through decades of teaching, designing and building, Caine turned obstacles into opportunities. His work remains a tangible link to Jacksonville’s mid-20th century Black history, a testament to vision, perseverance and the transformative power of architecture.

An enduring legacy: J. Burnie Caine architecture over the years